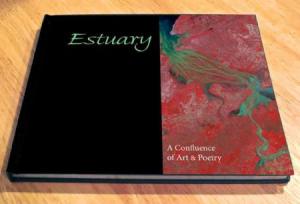

Estuary: a Confluence of Art & Poetry, ed. H. Lawler, A. Marton

-Reviewed by Ananya S Guha–

The basic tenet of Estuary is a synecdoche for the arts, a confluence, convergence or meeting point of art work and poetry. The editors point this out in the brief introduction, taking pains to explain literally what an estuary is, the meeting points of the river and the sea. This ‘explanation’ sets the trend for the metaphorical meaning of the texts and the art work. The fusion of art work and poetry is not uncommon these days, with literay zines using such aesthetic compulsions effectively and if one may say so, profitably. However, it is unusual to see it achieved as thoughtfully as is the case here, with art and poetry given the same amount of respect and, through their placement side by side on the page, forcing the viewer to find echoes of each other in the pieces.

The poems in this anthology are highly sensory, tainted by a deep coloration and sensuousness that brings out nuances between the real and the ideal, the make belief or the mythic, as contrasted with the real. There is a recurring imagistic use of shores, water, mirages, washing, etc in the poems which bind them into a thematic unity. The poems ‘Sand Dollar’, ‘From the Country, Sonnets from the Sea 18’etc typify such recurrent symbols, once again holding on to the estuary theme even if it be in a loose manner.

In line with the theme, a number of poems re-employ the anthology’s title, beginning with the opening poem, Kathleen Jones’ ‘The Estuary’, in which she explores the estuary as a preserver of memory, hoping her footprints will ‘last a few millennia / slowly fossilising / into bedrock’. However, Jones’ estuary is no peaceful or picturesque scene, its sludge is ‘deceitful’, ‘A boat has been drowned / in it’, while the sea is ‘too withdrawn / for conversation’.

In contrast, one of the end poems by Aad de Gids entitled: ‘Estuary Barcode Scanning’ takes a different approach, with a prose poem: ‘estuary // as if the fingers are forked within each other two flows of energy meeting a sea and a river meet’. It’s a dense poem, storing, not unlike a barcode itself, a wealth of information. Facing it is Hego Goevert’s artwork ‘Deus Ex Machina I’, which has a slight steampunk aesthetic with its gold pattern (mimicking wiring), and a fragility emphasized by the erasure of the design. Where de Gids’ work may be deemed alienating, Goevert’s complexity invites further observation, throwing the words in the shadows.

Elsewhere, the pairing of artist and poet seems like a more comfortable synthesis. Pippa Little’s ‘Zones of Convergence’ asks:

‘What washes up on different shores?

You walk with your camera, I walk with mine:

Orange globes, nets and lines, hasps, rusted pulleys,’

Little’s list of detritus has its shining moments, ‘the sea for all its muscle cannot swallow’ the trash it has been given. To which, Mark Erikson’s ‘Dusted Beans and Broken Beams’, shows the same interest in casting the lens of observation on the minutiae of the everyday. Little writes ‘our seas are strange to one another’, and yet here, artwork and writing collide in harmony.

Throughout the art work there are many such examples of finely tuned emotions in consonance with the jugglery of poetry. These pairings are the highlight of the book as they lead the poet to seek the hidden rationale for both poetry and painting. It is exactly this dialectic which gives the book its finely tuned talent of merging poetry and illusory truths with the graphics of art whether it is photography and digital art, or painting in acrylic or for that matter ink and paper. The range of the work is astonishing to view, like a riot of colours. One stand-out, Katerina Dramitinou’s ‘You Have no Idea How Early they Wake Up’, which uses photography and digital art, is an astonishing play of inner sensibilities contrasting with empirical realities of nature.

Estuary is a narrative of poems; I call them narratives beause each individual poem tells a story of the self in relation to the outside world. There is a turning inwards in some of the poems, a kind of introspection after the speaker detaches himself/herself from the subject matter. In most cases, there is an emotional distancing from the subject matter that is the object and the narrator, speaker or ‘listener’. Directness is a hallmark here but, at the end of most of the poems, there is a feeling of fogginess, the poet leads the way and the reader is trapped in a cycle of doubts. However, inaccessibility in these poems work to their advantage because at the end of each poem is a beautiful swirling mist, something you would love to see but something also that you cannot penetrate further. Does poetry need such penetration or incision? Reading these poems makes me ask this question and also the eternal question, what are ‘meanings’ in poetry? These poems all have layered structures and the edifice as a whole is monumental. Likewise, the paintings are abstract if not abstruse, but their very texture is finely knit and aesthetically very compact.

Peeling these layers of both poetry and painting has been for me, an exciting and stimulating experience.

Pingback: Saboteur Awards 2013: The Shortlist | Sabotage

Pingback: Gallery “VIEW” | VIEW

Pingback: Severin’s Choice: “Estuary: A Confluence of Art & Poetry” | The Alchemical City

Pingback: Saboteur Awards 2013: Published Poetry | Sabotage