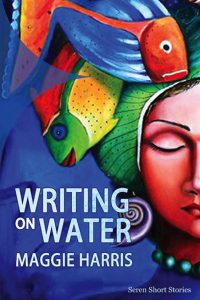

Writing on Water by Maggie Harris

– Reviewed by Jenny Booth –

What do migrants from the global south, troubled families dodging social workers, and menopausal women dreaming of bespoke kitchens have in common? One rather obvious answer to this rhetorical flourish is that they all feature in Writing on Water, Maggie Harris’ second collection of short stories. Her first, ‘In Margate By Lunchtime’, was longlisted for the Edge Hill prize; the opener in this collection, ‘Sending for Chantal’, won Harris a Commonwealth Short Story Prize.

A more illuminating answer might have something to do with which voices are heard and unheard in dominant narratives. This is something that Dolly, the brash ‘badass Caribbean post-col sister’ persona of the conflicted writer in the title story would surely have an eye for. Some of the voices in Writing on Water are, as the title suggests, ephemeral, struggling to be heard. One story follows Isxaaq, a refugee attempting a crossing of the Mediterranean from an unnamed African coast. Estimates put the number of people who died attempting these crossings since 2014 at over 15,000. Where do these voices get to be heard, except in writing that centres them as human beings? In other ways the lives of characters in the collection are written by water, by rivers that created the arbitrary borders of former colonies, the seas that they need to cross, and by the culture, magic and memories that rivers bring to their communities.

All this is well and good, but does a British girl who, as a consequence of trauma, is only able to speak to members of her dysfunctional family and beloved Barbie doll, have anything to do with African migrants? I think so, and I think Harris does too. This is one of the things that I liked about the collection, an awareness of the political circumstances of the characters’ lives, and a drawing of lines of solidarity between them by creating space for them to speak. This isn’t to suggest that these stories are dry or theoretical. The autobiographical epilogue, ‘On Inhabiting a Country of Words’, effectively summarises the ethos of these stories. It describes, from a child’s point of view, a growing awareness of how language is used; what is permitted, and to whom, and how this intersects with class, sex and race.

The collection experiments with a variety of voices, third and first person, men, women, children, different vernaculars; even a personification of a too-often closed Mouth in a story about a mother’s difficult relationship with her daughter. I found some of these voices more successful than others. ‘In Sugarcane for my Sweetheart’, the switching between Caribbean and English voices works to show the lead character’s internal conflict of identity. In ‘Telling Barbie’, I found the child voice more visible and distracting from the story. This contrasts with the epilogue, which, although similar in the way that it uses a child’s eye to make observations about the adult world they are growing into, felt more natural and unforced.

Whether the Guyana of her childhood or rural Wales where she now lives, Harris’s descriptions of landscapes are evocatively written. The writing shows close observation and a genuine appreciation of nature, as well as foregrounding it as an important part of her characters’ lives.

The language is often extravagant. A baby with eyelashes ‘like ethereal palm trees, lit by the moon’ might be too flowery for some tastes, although this does appear in a fairy tale, a Caribbean rewriting of Sleeping Beauty. Not all the pieces necessarily conform to traditional criterion for short stories. ‘Breast’ addresses changing attitudes to women’s bodies, sexuality and motherhood from the standpoint of one woman’s life. While it’s an insightful narrative of a life, there isn’t any obvious tension or resolution for the character most of the way through, and some of the gripes about the relative social acceptability of page 3 girls versus breastfeeding in public, while valid, aren’t perhaps the most revelatory.

At their best, these stories introduce complicated and sympathetic characters in immediate and believable situations, with subtle expositions of how power and politics act on human lives. It’s an interesting collection by an intelligent and, possibly more importantly, a generous writer.