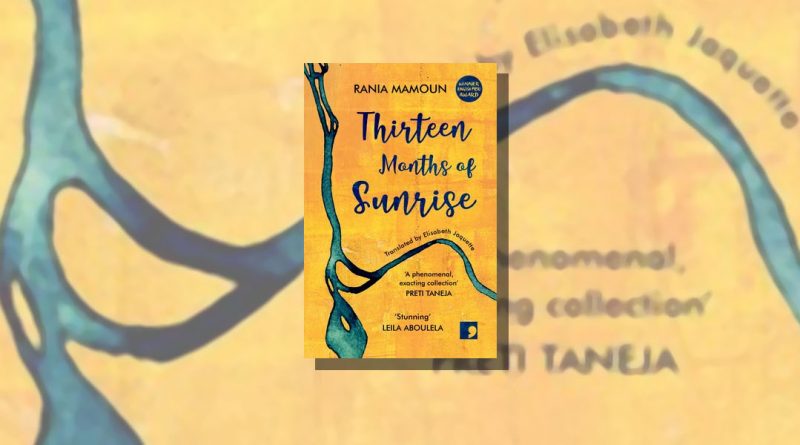

Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun

– Reviewed by Jenny Booth –

Rania Mamoun is a journalist and writer, author of two novels, Green Flash and Son of the Sun. Thirteen Months of Sunrise is her first short fiction collection, translated by Elisabeth Jacquette and published by Comma Press. The Sudanese writer Jamal Mahjoub writing in the Guardian speculated that Thirteen Months of Sunrise could be the first short fiction collection by a Sudanese woman to be translated into English.

Fiction seems to develop conventions of talking about things like families, love and disadvantage. Partly this reflects the idea of writing responding to a conversation or tradition. Sometimes a piece of writing startles the reader into new ways of seeing things. To an English reader, Mamoun comes from a different tradition, perhaps of African or Arabic literature. From reading the stories, I learnt something about; the music of Hafiz Abdulrahman, Othman Hussein, Mostafa Sid Ahmed; the Ghezira scheme, Africa’s largest irrigation scheme (Wikipedia has a staggering aerial photo of the canals); and Khartoum, the confluence of ‘the unruly Blue Nile, and the wide, calm White Nile… where their beauty glorifies the city.’

The collection offers more than literary tourism, more than just an opportunity for the English reader to dip their toes into exoticism. It’s an important corrective to how Sudan appears in ‘Western’ representation and imagination.

In staples of Sunday afternoon TV like The Four Feathers, Sudan appears as a background to acts of British gallantry and valour in the face of hordes of savages; in the actual Battle of Omdurman, 48 soldiers on the British side died compared to 12,000 Sudanese Mahdist soldiers. More recently, Mamoun’s writing appeared in Banthology released by Comma Press as a counter to Trump’s racist ‘Muslim ban’ that discriminated against Muslim majority countries, including Sudan. In 2011’s census, 17,000 UK residents are from Sudan, and 160,000 speak Arabic as a first language. Is it therefore meaningful or correct to draw distinctions between ‘British’ and ‘Arabic’ literary traditions, when modern British writers and readers encompass traditions and languages from across the globe?

Whatever the reason, I found the stories that I enjoyed the most, ‘Thirteen Months of Sunrise‘, ‘Passing‘ and ‘A Woman Asleep on her Bundle‘, had striking and unusual ways of looking at familiar themes. In ‘Thirteen Months of Sunrise‘ the narrator (also called Rania) meets a man from Ethiopia, Kidane (he says Kidana) Kiros, who is working in Sudan. Kidane is lonely and homesick; Rania feels a deep affinity for the ‘Abyssinian’ culture of Kidane’s homeland. Kidane connects with his home by teaching Rania Amharic and Tigrinya words; Rania feeds her deep feeling for Ethiopia and Eritrea by listening to his tales of ‘Muslims from Harar, beautiful men and women who still live in cities surrounded by huge walls like ancient citadels’. When Rania wants to recall Kidane, she tells someone the fact he taught her, that the Ethiopian calendar has thirteen months. Their story foregrounds a way of loving someone that is unusual in writing;

“When he said ‘I feel at home in this country,’ I was filled with joy that I’d managed to ease his sharp loneliness.”

It’s both particular and universal in that all love might have something to do with finding home or belonging through other people.

In ‘Passing‘, the narrator describes being haunted by the memory of her father.

“Your scent opens channels of memory, it invades me without warning, like armies of ants stinging me fiercely, chaotically: on my eyes, my skin, in my pores, my blood, even my ears, as they pick up the vibrations of your voice drawing closer. I’m flooded with memories: I feel the warmth of your embrace; the warmth of the bed where as a child I slept beside you instead of Mother.”

It conveys the overwhelming nature of the narrator’s feelings. It’s also unusual in the way that it is almost erotic. This way of writing about loss tends to be found more in narratives of break ups and broken hearts, rather than of deceased parents, but there’s no reason why this should always be the case. The narrator’s failure to fulfil her father’s wish for her to become a doctor is poignantly told; the tension in the story comes from the inadequacy of medicine to either preserve or comprehend things outside of its scientific scope that are nevertheless integral to life. ‘Passing‘ also has a warm and touching account of growing up in a devoutly Muslim family.

‘A Woman Asleep on her Bundle‘ is a portrait of a homeless woman who has taken up residence by the wall of the narrator’s local mosque. Rather than presenting her as a victim to be pitied or even empathised with, Mamoun presents her as a powerful, mysterious person.

The unnamed woman walks to ‘her own rhythm, her own sense of harmony’; when the streets clear in bad weather, ‘she appeared shortly afterwards like a rainbow.’

The detailed observation conveys something of real importance and depth about the character of the woman, with very little dialogue or material explanatory facts. It also reveals something about the narrator, and what meaning the woman has for her; whether she presents a rebuke to the relative conventionality of the narrator’s life, or a reminder of social injustice. The ending is beautifully ambiguous,

“I longed for her and thought about helping her or inviting her to come home with me, but I always feared how she might respond. I feared her stones that lay buried in my memory, because just like all villains, I too had fears.”

The compassion and close observation of the poorest and most desperate people in society is something I admired throughout the collection. However I found some characters, possibly in ‘Doors‘ and ‘One-Room Sorrows‘, more one-dimensionally defined by their circumstances, even while the stories were explanatory of the structural injustices working against them. Similarly, all of the writing is imaginatively daring and poetic in its approach, but not all the stories delivered the same depth or impact. I felt the one page story, ‘A Week of Love‘, while having the same qualities of mystery and unrealness, was one of the weaker points.

Rania Mamoun’s writing is insightful, funny, and wholehearted in its exploration of life. If more short fiction by Sudanese women became widely translated and available, it’s possible that these stories might feel less unique and fresh; but I was very grateful for the opportunity to read this collection.