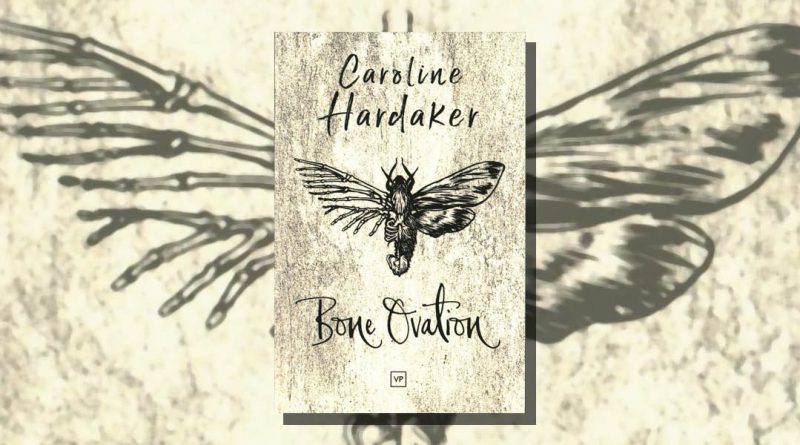

Bone Ovation by Caroline Hardaker

-Reviewed by Phoebe Walker-

Caroline Hardaker’s debut poetry pamphlet is a triumph of contemporary myth-making. The poems in this slim collection concern themselves with the fantastical and the half-feared, the dream and images lurking at the elbow of everyday consciousness. Despite its absorption in the other-worldly, which often shades into darker themes, there is little here that is distinctly unheimlich; rather, the poems are by turn curious, wistful and perplexed meditations on ineffable matters, and this pulse of fascination is kept steady and engaging throughout.

Transfiguration is a strong theme throughout this pamphlet, and both humans and their once-inanimate surroundings share various transmutations which veer from subtle to alarming. In ‘The Girl Who Fell in Love With the Mountain’, the girl is “received into earnest mud; an ancient epidermis of soft heathers, grass/ and gallant crags”. Elsewhere, ‘The Paper Woman’, her “lace skin shimmering” remembers when “she brushed away stray fingers like matches”. An indignant balloon protests “Must you press upon my skin/ your radicalisations?” (‘Balloon’). In ‘The Man Who Was Made of Bees’, “unassertive/ but smiling George” has “a glow born of more stately stuff”, he stings people by just brushing past them, “bristles with white noise […] smells like drying wood.” Against these purer, often playful flights of transformation, Hardaker is also acutely aware of the quieter modes of change, intensely relatable and yet still extraordinary. Her power of metaphor is strong, as in ‘Womb-light’, where the central figure, out for “a midnight dip”, is implored to ignore “The glittering flickers” which are “not stars but sucking weights”, and to

[…] Leave the weight of you at shore,

slip off those chiffon wings, they’re false feathers

The theme of flight (or grounding) is revisited throughout this pamphlet in images of wings, bird bones and eggs, those quotidian mysteries, which

[…] are born in our mouths, crowned around

with a wreath of tawny feathers we invent with speech,‘Your Bones and My Bones are Chicken Bones’

Hardaker knows the power of such symbolism, particularly the symbolic strata that make up a myth, and negotiates this potentially stodgy territory with care. In ‘Clansmen’, a dying father wishes to “play/ with those who ward the cusp of this earth”, and waits “for the shore to break, for the leap of a fish or a tail, for the rise of his pack”. It’s a rare point in this pamphlet where the poem threatens to collapse under the weight of its own solemnity, but is saved by its elegant final lines. Points of gravity are counterbalanced by poems which skewer the everyday in a manner both agile and arresting: tired feet are described as

[…] stumps, stollen lumps

I press nightly to knead the butter out[…] I soak them,

root them like bulbs

amongst nimbler water lillies

In ‘Pestle and Mortar’, the rhythm of a domestic task is twinned with the pattern of thought, “[b]lindly grinding down choices […] instinct knows/ the way from brain to pulsing vein.”

This pamphlet has a heightened consciousness of the poem as story and of the person as story, yet despite this preoccupation with fiction and fantasy, there is a strong and refreshing undercurrent of realism. This comes not just from its subjects, the poetry of the everyday explored through scenes with bored grandmothers, frustrated ex-lovers, furious dinner preparations, but is finely expressed through moments of lucid and uncynical language that scythes through the murky business of fabulation. As the title poem tells us,

It ended up in death, I remember,

whatever the sound was

Bone Ovation revels in its mythologizing of the ordinary, and has much to engage any reader in that vein alone; but it also offers a more generous and eloquent view of the power of transformation, without romanticizing it. These poems offer a striking argument for the significance of storytelling.