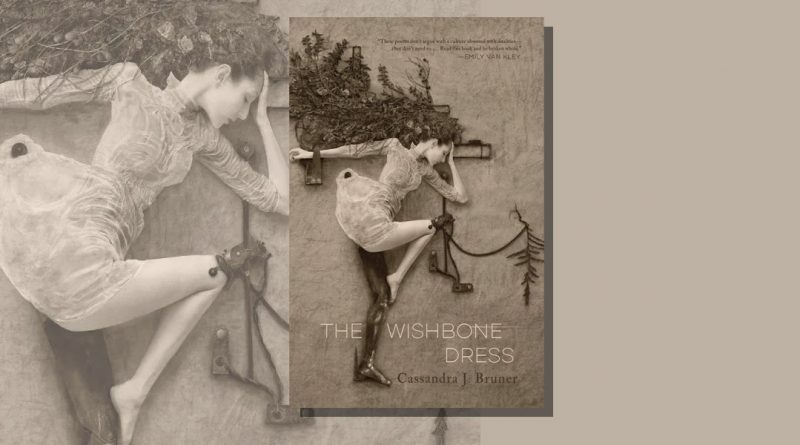

The Wishbone Dress by Cassandra J. Bruner

-Reviewed by Deirdre Hines-

Cassandra J. Bruner is a transfeminine poet, whose chapbook ‘The Wishbone Dress’ is the 2019 recipient of The Frost Place Chapbook Competition, selected by Eduardo C.Corral. It is one of the best books of poetry I have read in the last year.

The reader is presented with nineteen poems that reveal what it is that differentiates trans experience from a cisgender perspective of transness. Instead of entering poems where the worldview of cisgender dynamics dominate, dualisms and absent referents of the trans experience abound. Her poems bring us closer to a worldview that incorporates transgender dynamics and questions all dualisms that absent any reference to the trans lived experience.

Bruner cleverly skews our perceptions of the biblical origin myth of the female in the opening couplets of ‘Frontispiece’, the poem with which she begins her seduction of our constructed gaze

I think of how gods prefer their oracles

blind & their prophets impotent,

how two milligrams of estrogen

was enough to mold Eve from a shard of bone.

Later in ‘Frontispiece’ Bruner’s great-grandmother speaks as the lemon rinds the poet rinses her mouth with:

Child, your hips have already fused.

A gash in my mouth sings

of all things made new

as it hardens like a cataract.

The poet’s pulling of language, as she calls it in the Notes and Acknowledgments, from Isaiah 42;9 and from Revelations 21;5, affirm both prophesy and change. In many ways, this chapbook is a telling of the future before it happens, just like in Isaiah 42;9.

Desire to be another, desire for another, desire as ancient as that of the Beloved in Song of Songs, denied to the other by popular philosophers such as Slavoj Zizek is addressed in ‘Aubade with Ball Gag’. It owes its epigraph to Zizek, and reads as follows: ‘Masturbation’ is the ideal form of sex activity for this trans-gendered subject’. The aubade is a delightful retort to Zizek’s pontification. Written in sixteen broken lines divided into two quatrains, two tercets and ending in a couplet, the poem depicts sex between a transfeminine woman and another woman. It is stunningly brilliant. The poet imagines that the coupling women look like one woman from afar, a direct reference to Zizek’s disbelief in the existence of desire for the trans person.

this weave of straps and copper we must look like

a lone woman who can’t stop

touching herself

She invites us to ‘lean/closer & hear the cries crackle/ along my jaw like hooves’. The final couplet is as quiet as the aftermath of sex; ‘At the unclasping our twinned watermark/our afterimage fading’. In another poem, ‘Of The Night’ Bruner asks ‘Is/desire always defined by its negation, its absence?’ There is an erudition behind a Bruner poem that could elude the less careful reader. Earlier in this same poem the poet’s mother’s obsession with harlots is her devotional and is named as ‘Bad Women of the Bible’.

Tracing makeshift lineages of harlotry, the book says

Azazel set apart the first whores when

he gifted us knives & make-up

The origin myths of harlots outlined in her mother’s devotional include pagan gods, screech owls and Lilith. The Lord is voyeuristic and ‘by His will, a womb must always/ give birth to something’.

Such an introduction prepares us for Ann, the sex worker the poet is skyping, and when she tells of Ann’s Siberian husky licking salt from her fingertips we are not surprised by the reference to ‘Jezebel & the rabid hounds’. The biblical motif segues quickly into a remembered name-calling from a client, when sweetheart morphs to cunt, as she is brushing ‘her orchiectomy scars’. The poet considers how synonymous flesh and judgement is, and reveals how a lover mistook her thighs ‘sore-peppered’ from Crohn’s for AIDS, but instead of explaining she walked out. The poem ends with an image of kneeling, of supplication, and asks the reader to ‘Name a god who is a Hooker’ whose laws call for fluidity. Only then will she and others like her kneel in supplication ‘unfurling/ our perfumed nests of hair in offering’.

Her handling of the supernatural referent in ‘Cora, Bound to the Tree delivers her Testimony’ and of the American folktale of Cora the Witch exceeded all my expectation. Bruner handles the long line and suspense very well indeed, and her imagery is exquisite. The folktale is set in the 1700s and allows Bruner to adopt the persona of outlaw mother. No surprise that the baby is magicked from a proboscis dipped in ink, a baptism in fermented oranges and a name inscribed in a ‘book shellacked with/ the still-clicking beaks of humming birds’. If this book has a backdrop sound it is of insect murmur and hiss.

A wish is made with a wishbone by breaking it. In a society that favours symbolic thinking, Bruner manages to be heard about literal matters. This is no small achievement. In ‘Object Lessons After Solomon J. Solomon’s Ajaz and Cassandra’ she asks ‘Who can survive/ becoming allegory?’. She has broken the traditional frame of the poem, and created a new one. I salute her courage.

Bruner has charted her rebirth and nowhere is that more beautifully described than in the poem ‘Hiraeth’ and the first line ‘Every girl must know her annunciation’. Bruner has known hers in all its shades. If you read this book you will know it too, and be the wiser and the more compassionate for it. A necessary buy for those that advocate plurality and indeed for those who do not.