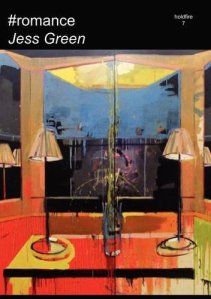

‘#romance’ by Jess Green

-Reviewed by Éireann Lorsung–

Imagine—maybe this is easy, maybe you have to strain a bit—that time when you were just done with university. Anything could happen. Hopped up on the expectations and praise and challenges of your tutors, you head out into the world. And then what? In Jess Green’s chapbook, the ‘then what’ is drinking gin, making noise, writing poems, hoping for emails from someone who rarely writes, following people on Twitter.

Jess Green’ chapbook #romance is about moment. We know this not only by the hashtagged title (which is nothing if not of our moment, not to mention the signifier of things which, in a moment, will no longer matter or even make sense) but by her insistence on the now of the poems, which happens also to be our recent now, in a very specific here. We’re in England, 2011 or so, in these poems. We’ve got a Royal wedding (as distraction), dinners with the Beckhams, and a rather heavy-handed mention of class war (“Stop the Poetry”); we’ve got Coronation Street as signifier of class; we’ve got Red Stripe and D:Ream and Outkast and Match.com, Dyson dryers and David Tennant as Doctor Who (“Potatoes”). The poems mention GCSEs, BTECs, the ‘Daily Hate’, iPads, Kindles (“Beyond the Kettle”), coeliacs, Bargain Booze (twice), and Primark, Wigan and Toxteth and Eton and Egg Café. Although Shakespeare, Eliot, Keats, Browning, Plath and Hughes make appearances, it is notable that most of these take place in a poem (“Scratch Your Degree”) which imagines, with irony, the erasure of three years of university. The past—including the literary one—is not the primary subject of the poems, despite its importance to them and to their speaker.

The insistence of these poems on their moment, on the now of hashtags and pop culture references and gadgets—but also on the now of just-out-of-university, the now of being in your early twenties and not knowing what will happen and kind of flailing a bit—is double-edged. On one hand, it makes the poems urgent. Green very clearly evokes a certain desperation, anxiety, and mania that often accompanies early adulthood, and the references to the speaker’s surroundings, whether geographical or cultural, site the emotional experiences in the poems. But the now-ness of the poems also makes them feel closed off, topical, a little predictable. In “Stop the Poetry”, for example, the speaker’s protest against the conservative government (one which will “spend our pensions on dinner with the Beckhams”, “[distract] us with a Royal wedding”, “penalise the unmarried/and patronise the women”) is unsurprising. The poem ends with the image of an unstoppable poetry “telling the tales of the war you’re raging/ on the unrich, the unprivileged, and the unmiddleaged [sic]”. In all its sincerity (and for this reviewer that is a value-positive word), the poem seems to have forgotten that other poets have written in the face of repressive governments. Poetry really has survived and helped others to survive—need I mention Akhmatova, Neruda, or any other famous examples?—but in order to do this it must reinvent the world, actually re-form it, not just re-present it, with the fugitive promise to “prance along bars until they listen”. When the poems take on these responsibilities, their now-ness is a hindrance to them, because a lasting political poem must be about more than its subject. But perhaps here again Green is emphasising the ephemerality of things; perhaps the poem is not meant to last, not meant to speak beyond its now any more than today’s hashtag on Twitter would, three weeks from now.

Green seems to aim to fulfil Ezra Pound’s dictum to make it new by introducing new things to the poems. The titular hashtag, for one, is successful: it disrupts the habitual reading of a word and a title and forces the reader to reconsider the function and form of each. Writing about recent occurrences, however, is not enough to make a new poetry. Many times reading this chapbook I found myself wishing for more consideration of line, of image, and of language that would convey the immediacy and desire that seems to be the root of these poems. The poems do feel urgent, but they also feel sloppy (and, unfortunately, the book’s production and editing add to this—my copy had poorly aligned pages which stuck out above the cover, and I was disappointed to find typographical errors and inconsistencies throughout the text).

Despite my desire for more depth and richness here, Green’s willingness to be vulnerable, to be sincere, to write about “being nineteen/ and so desperately wanting to be fucked up” (“Another one broken”) and to “stand up/ and speak my secrets to strangers” (“Potatoes”) are strengths, and the willingness to be vulnerable especially is rare and necessary. #romance, with its emphasis on what passes, ends, disappears, and fades away, tells an aching and raw story of its speaker’s early adulthood. Whether or not that story is destined for the same “half of a bottom shelf” where the library keeps its “useless ancient monologues” (“Scratch Your Degree”) is perhaps beside the point.

Pingback: » Archive » Two reviews at Sabotage Reviews