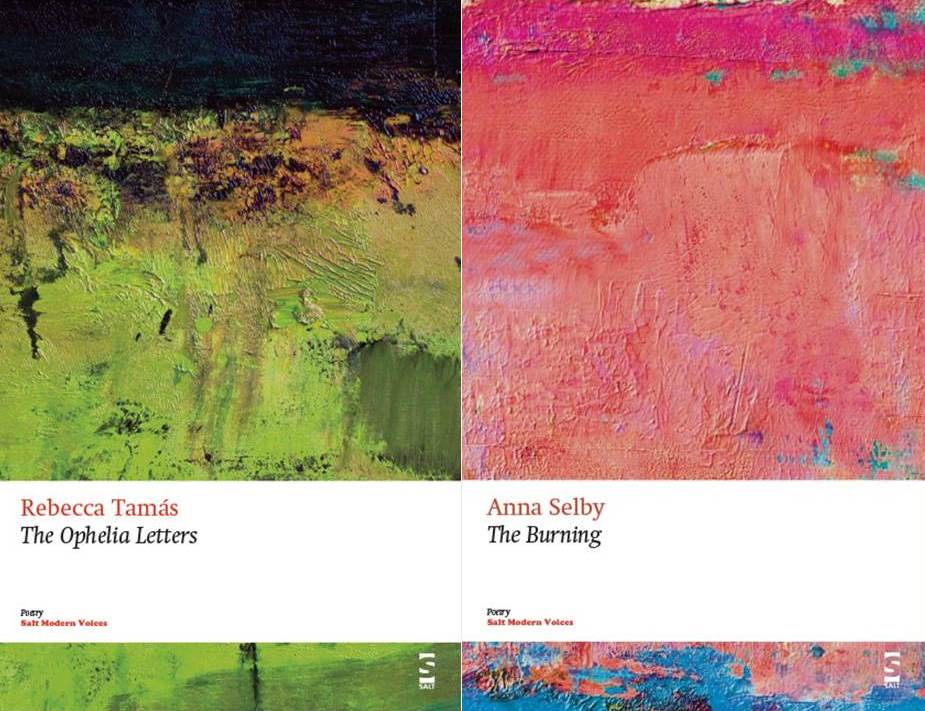

The Ophelia Letters by Rebecca Tamás and The Burning by Anna Selby

-Reviewed by Paul McMenemy–

The first poem in any collection has a lot of work to do, introducing themes, images, a tone, which will be developed in the rest of the work. Often this burden can make it the least satisfying in a collection. And ‘Hare Window’, the opening poem of Rebecca Tamás’s collection, The Ophelia Letters – indeed all six of the poems preceding the long title sequence – seems at first a distraction from the main event, which could have sustained a pamphlet on its own. However, on repeated readings, it becomes clear that the initial poems prepare the ground for what comes after.

Even within this context, though, ‘Hare Window’ seems anomalous. The other introductory poems take us on a tour of wild and cold places – the Small Isles, Dorset, the unnamed locale of ‘A trip with Werner Herzog’; even Edinburgh is presented as ‘Vertigo City’, a rock in a sea of sky. ‘Hare Window’, though, takes place in a domestic setting, and is, in part, about the end of wildness. Nonetheless, many of the forthcoming themes are set up: the hare is brought in “limp in its own blood” – blood splashes the white of many of these pages. The poet has previously seen the live hare “familiar like the flicker / of a lover’s shirt on another back / amongst the crowd” – this engaging simile foreshadows the absent Hamlet of the title poem. The living hare’s eye was “a capsized star / marking the pull of light around the fields” – this concern with light and emptiness is central to the collection.

But there is something else happening in the poem. The poet sits “hotly” in the midst of the scene, obscurely mortified by the presence of the cooked hare. The living hare is identified with the poet, or her poetry – it is

“a hung note stretching the song

between the word and its sound,

language riddled with blue pockmarks,

acres of sky.”

She imagines that should she taste it, dead, she would taste her “own slick tongue.”

This heat seems to sit uncomfortably with what follows: the hungry earth of Eigg, pulling cars, houses, people into itself, flattened by the weight of the massive sky, the isle’s edge-of-the-world feeling subtly captured. ‘Rùm’ is perhaps less successful: the island’s incongruous Scotch Baronial palace, constructed by a bisexual Victorian industrialist, is nicely depicted; its juxtaposition with the story of a modern woman working on the island “without any of her old lives, / her difficult past” jars. The two form a diptych of tales of running away – or to – but, as with that redundant line, “her difficult past”, one feels that the poem aims too hard for summation. But again the final lines, “She drinks her water unfiltered, / mouth to the stream” – too easy in the context of the individual poem – reinforce the coolness and clarity intrinsic to the collection.

Coolness, clarity and an oddly visceral impersonality: ‘Compton Abbas’, about the poet and her mother, is full of “brief shouts of rain”, “wide mouthfuls of air”, “grey light”, “wind”, “waters” and cunningly empty of the hinted-at strained relationship; yet Tamás presents the consolation of the initial gift given her by her mother – life – as something more than cliché, without sentimentality or idealisation (her mother – to whom the collection is dedicated – “threw me out of her blood”.)

All of this is a subtle preparation for ‘The Ophelia Letters’ themselves, nineteen sections written in a character composited of Shakespeare’s Ophelia and, apparently, Tamás herself – one suspects that the cold of Elsinore has been transplanted to Edinburgh. The letters detail the obsession of love, now turned outwards towards the absent lover:

“I used to dream you were my brother,

at least then we could kiss in public,

share the bath.”

Now, and more often as the poem progresses, inwards:

“Soft and sharp like an opened pear

my womb ticks away.”

The whole thrums with a beautiful (indeed, Herzogian) bleakness. At one point Tamás says, “Clarity, that’s what I keep looking for”, and each image has the precision of a clap heard in the dead silence of a bright midwinter night. An example – perhaps the key to the work – is a reminiscence of sex on a snowy day: “A whiteout, a miracle delivered to my own measurements.” The poet (or Ophelia) identifies herself with the erasing snow, as she seeks annihilation in love. “We were invisible […] We were no one, / our own ghosts, […] It was so cold we couldn’t really have been / said to be alive.”

“For a second I could peer down the empty brightness

and think of loving you.

“If only it could always be like that,

clear, appalling,”

Into this glacial landscape erupt jolts of carmine physicality – the whole is a mixture of blood and bloodlessness – which nonetheless do not thaw the whole; but towards the end we do get images of melting – a cold, washed-out spring – which remind us of the end of Hamlet’s Ophelia. Perhaps also it gives us a clue to the “hot” discomfiture of the poet at the start of the collection, another Ophelia, dragged live from her coolness back into the messy world.

Despite its title, Anna Selby’s The Burning also begins in the cold. But ‘The First Time I Saw Your Winter’ immediately discloses a difference of focus. It deals with language as a window into another’s way of looking at the world. In a sense The Ophelia Letters are a young person’s poems (Hamlet and Ophelia were as intense, as adolescent, a pair of lovers as Romeo and Juliet). Tamás’s sequence is stark: not black and white, but black, red and white, mainly. There is little outside the lovers’ world (and really, outside Ophelia’s world and her conception of her lover) – they exist in blankness. In ‘The Second Dance’, Selby also describes a pair of lovers, but they are warmer, more corporeal, perhaps more real in terms of how they see themselves:

“We will be realising

we don’t love each other,

but we haven’t told our bodies

and our hands have made a spitting fire

the buds of our knuckles unfold to.”

Yet these poems, too, have a coolness (“the burning”, we are told, is a term describing phosphorescence). A poem like ‘Washing My Father’ is not as physical as we might expect, till near the end: “Why do you lift your father like a drowned man? Sadness asks. / Huge waves are breaking over the burnt-out pier.”

Many of the poems are set in, or by, water, which creates a kind of remoteness which, in the most successful poems, emphasises feeling, as in the ‘Death of the Fish March’ which begins by describing gulls following a trawler as mourners mixing disingenuousness with real grief:

“Gulls flipping themselves over with grief,

a flurry of grief, grief the slow motoring

chug, grief the car kept ticking, grief shoving

grief out of the way for a glimpse, grief the white handkerchiefs

waving them off […]”

Before: “My grief wonders what my grandfather whistled, / what tune it was that made my grandmother follow.”

As the extract above shows, Selby is more obviously interested in sound than Tamás. Poems like ‘How Sundays Would Sound if People Described Them’ (‘A fly dies on a windowsill. It rains / a lot in a small town’) which fizzes with ‘s’s and ‘x’s and ‘f’s echoing these initial two images, produce a crackling euphony that is extremely satisfying. However, this perhaps masks a lack of intensity, a certain complacency, in some of the poems. ‘Timelapse’ deals with the uneven, unbelievable speed with which life passes, ending with “You should lie down now. Have a power nap. / It will be autumn next time you wake.” There is a composedness about that last line which does not quite sit – it replaces horror with a shrug – it is a little too pat, too finished: we are reminded that we are reading a poem. This might be best summed up in the last poem, ‘Duck Eggs and Keats Instead of Grace’: it is a perfectly pleasant-sounding recipe for content, but perhaps a little cosily middle-class? There are too few moments where emotion spills out; too little jeopardy. The danger of water quickly evaporates. ‘52 Versions of Hope’ warns of the dangers of exposing one’s feelings, and the greater dangers of not doing so (again, in a slightly too-artful manner). This collection could do with heeding that advice.

Ultimately, these pamphlets are both very good, and comparing them does not necessarily do a service to either. One thing they do both do, though, is highlight how disappointing it is that Salt is soon to stop publishing single-author collections. Also, one wonders – at £6.50 each – just who exactly these nicely, but obviously cheaply, produced pamphlets are aimed at. I would happily read a longer collection by either of these poets, so I must hope that Salt reconsiders its policy, or another publisher steps into the space it has left.