The Black Light Engine Room #8

-Reviewed by Alex Campbell–

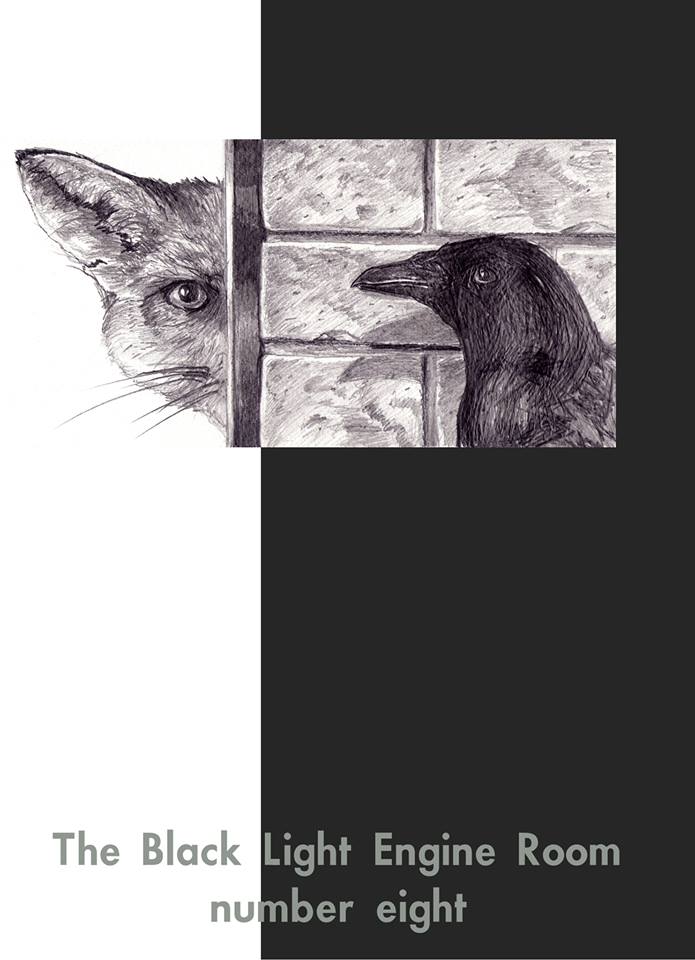

In line with the delightfully Gothic cover, there is a darkness that runs through this collection; by turns weird, creepy, bleak and hopeful, there is an undeniable strength of feeling in The Black Light Engine Room. Being from Newcastle myself, this Middlesbrough magazine strikes a chord with me, and I feel echoes of my home in a lot of the poems and short pieces. The grit and realism that feels characteristic of the North East permeates the collection. This is Poetry with bones of steel.

But like bones, there is something of an unfinished quality to the magazine. Sometimes this adds to the emotional impact; the lack of extra “flesh” lets the real, rawness of the emotion shine through more readily, as in A.J McKenna’s “25/5/13”, which reads like performance poetry (and a quick glance at her bio reveals that she is an accomplished Slam poet), and Andy Willoughby’s “Americana” which has overtones of Kerouac and Ginsberg, whose pared-down, beat style he shares, as well as having a similar content. Other poems in the magazine are less well served by this roughness.

Sky Hawkins’ “Empty Nest”, for example, suffers from lack of polish. A good poem overall, a few lines could still have done with a bit of judicious editing to improve the scansion, and the penultimate stanza feels trite and cliché, as if the poet is reluctant to dig deeper into the grief of an absent son. “Relief is brief/ Then turns to grief,” would have sufficed, or more in the same vein. On the page, the longer lines with their bouncy rhythm, shorn of the repeated “no more” refrain and the “Click clack,/ Don’t come back,” even look like they don’t belong. Without that stanza (or with it modified) this would have been a brilliant, authentic feeling poem.

And “Empty Nest” isn’t the only poem with such difficulties. A different, but related, issue surfaces in “Life and Death in a Northern Town,” by Harry Gallagher. A stark and bold portrait of economic depression in the North, its simple repetition of “This is how I fell,” generates pathos without being sentimental, and is overall a strong, emotive poem. However, the introduction of “Having Bi-Polar Disorder” near to the end, I feel, jerks the poem out of the path it had begun to beat. While I appreciate the poet’s openness and willingness to bare all, this feels forced. While the other issues are presented as single incidents which build up and layer to form a cohesive whole, mental health issues are an ongoing problem. Had they been presented as a singular event, in the form of an example of how this affected the poet, it would have blended more seamlessly, and I can’t help but wish it had been so.

Likewise, Juli Watson’s “The Bigg Market” spoils an otherwise gorgeously euphonic, alliterative poem filled with such gems as “streaked teak skin,” “A rota of replicas / Vicious variations…” “All shrieks and scripts,” with the addition of a final line “Prostitution 101?”. It’s a disingenuous question, introducing – unnecessarily – the writer’s overt moral judgement of her subjects, detracting from the reader’s ability to form their own opinion and sounding harsh and bitter. It betrays a lack of confidence in her own writing, which is thankfully absent from her other piece in this collection, “8pm”, which is stronger for it.

It’s not big things which pull this collection down. Tiny, rough edges like these, grammar issues, misplaced apostrophes and typos sadly dot the pages, but to carp about that feels petty, since there are, nestled in the midst of this collection, some wonderful, shining poems. The fantastic “25/5/23” by A.J McKenna. “Metrolife” by Pippa Little, which made me, I will confess, more than a little homesick, as did Margaret Williams’ “Letter to the Angel”.

W.N. Herbert’s “The Passionate Psychobear To His Love” was gloriously gothic, inventive, and was vaguely reminiscent of Andrew Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress – phrases like “then with my littlest claw… now / lo! Observe its pomegranate roe,” and “the shriek-owl’s song’s more to our taste,” have echoes of “The grave’s a fine and quiet place/ but none I think do there embrace,” but even for those who aren’t a fan of Marvell, this gruesome little love poem has a delightful lightness of tone that counterpoints the creepiness perfectly.

“Condom” by Tom Richardson is one of those poems that just perfectly captures an insignificant moment, and places it in a wider context, giving it all the significance of a lived experience. It’s short, but every word seems perfect – epitomising the saying that a thing is finished, not when no more can be added, but when no more can be taken away. David Rudd-Mitchell’s triptych of poems, “Pre-Match” “The Match” and “Post-Match” likewise have that economy of style and a precision that can’t but be admired, and the extended metaphor, comparing a testicular cancer scare with a football match, is elegantly executed.

But for me, the crowning glory of the collection is “Light Gardening in New Eden” by Robyn Ollett. Never having seen Night of the Living Dead, which the poem is a self-styled “transformation” of, I was concerned that I would not fully appreciate it, but I needn’t have worried. It is a rich, layered poem, full of gripping imagery (“outside they are young together in Napalm” “the scream Queen’s gone mute”), deft word-play (“It was a good year,/ in the tyre feet of / Goodyear” “One out of her head, one in a frying pan’s fire”), and a breakneck pace that, to me, evokes the ghost of Plath, let alone Romero. It is a joy to read, and an amazing centre-piece to a collection that, from first to last, refuses to let you go.