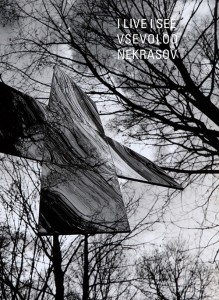

I Live I See by Vsevolod Nekrasov (trans. by Ainsley Morse and Bela Shayevich)

-Reviewed by Sarah Hymas–

the cause of death

was livingthe immediate cause

of death wasliving in Moscow

This review will only scratch the veneer of this immense selected works. It will have far too many words, words that only have one meaning whereas the words used by Nekrasov are sparing, ambiguous and treated with great reverence. They teeter on the precipice of expansion and containment, of humour and deadly earnestness. It is this precariousness, and the risk taken by such a position, that gives his poems such power.

The translators’ introduction states that Nekrasov was awarded the Andrei Bely prize in 2007 for “the uncompromising revelation of the poetic nature of speech […] an outstanding contribution of a new poetics, for half a century of creative self-sufficiency.” Creative self-sufficiency is probably what fueled and sustained such a searching, witty, angry and exacting body of work.

Nekrasov began writing in earnest in 1950s Russia, where this selection begins, running right though to his death in 2009. His work both reflects the time in which it was created and rejects it, or at least, reaches beyond it. This stretching – back and forward – is perhaps more evident in the latter two sections of the book, where he overtly, and ironically, compares Stalin and Hitler, and where he considers the society beyond his lifetime.

This last sentence probably implies work more literal than it is.

The translators deserve a prize too: for their ingenuity as well as the sheer volume of what they’ve translated. Nekrasov was fond of repetition, of puns and idioms, often playing with a single word or phrase over and over in one poem. This lack of context creates a difficulty highlighted by the example of “nichego” which means both ‘it’s alright’ and ‘nothing’. If that single word is repeated for the poem, then which meaning should the translators choose?

There are plenty of poems throughout the collection that repeat words or phrases (of the same words in varying order) pushing at their meaning, forcing a change of meaning, shifting the tone, and challenging the reader to reconsider what they mean. Poem after poem, year after year: his questioning of how language is used and received was his life’s poetic expedition.

The poem that opens this review is a short shot of an example that highlights how the repetition gives unexpected weight to words, symbolism and meanings shift and expand and then are undercut by the enforced change in tone that comes after insistent repetition, and a mocking or ironic commentary appears.

When used in less forthright poems, this repetition reveals Nekrasov’s other interest, for which he won the aforementioned prize: the poetic potential of speech. He called his poems ‘scraps’. Their abrupt beginnings and endings simulate those conversations either overheard or half-formed, but nonetheless urgent. Despite their self-depreciating moniker, they are not throw-away. This didactic mode highlights the surface meaninglessness of what we say, how we say it: perhaps most evident in institutional conventions. Of which he had plenty to mock.

well and

well and

well and

well and

well and

well and

well andand how

whatever

I think

like

most likely yeahbut like most likely

nolike no

the sky shouldn’t look like that

In this selected the ‘scraps’ are as plentiful as the piercingly accusatory poems that call for freedom of speech and for comparisons between religion and politics. Then amongst these is the short section from 100 Poems. This is a sequence of reprinted visual poems that dance around the photocopied pages in the form of flow charts, pie diagrams, clenched lettering, concrete poetry of the most scant shapes, playing with punctuation marks that create a powerfully continued energy within this section. Each facsimile has a corresponding page for non Russian readers, translating the words and giving any explanation to the ambiguity of word choice, and context. These add to the space of Nekrasov’s intention, and allow me to enter it twice – as visual reader then with literal comprehension.

I particularly appreciate the space the publishers give to the ‘scraps’ and other short short poems that fill the selection. Two line poems are, rightly, given an entire page to inhabit. You cannot set anything else on the same page as

The Soul

/just kidding/

without stealing its thunder, its humour, everything that has gone before, and continues to go around, it.

There is plenty of humour cut through the collection. Wry, knowing humour that rises so simply from all the devices I’ve mentioned. Then there are the footnotes that create boxes of the poems. Footnotes which are often small poems/‘scraps’ themselves, some of which then have their own footnotes. And so it goes. This mockery of officious documentation and extensive addendums is one way Nekrasov implicates place within the poems.

People are named as occasionally as place, but the themes transcend the localised politics of the poetry, even if they are what ignited the poems. Freedom, rules, unity, the mother, secrecy and obscurity are picked at, reframed and repeated.

I repeat

this

cannot

be repeatedI repeat

this

cannot

be repeatedI repeat

this

cannot

be repeatedthis

cannot

be repeatedthis

cannot

be repeatedI repeat

Picking out poems to illustrate this review has been difficult. The collection is huge, providing poems to enjoy and others that do little for me. And while perhaps this ambitious collection is, at first, over facing, I do think this many poems are needed to present his lifetime of work fairly. In one sense, it’s a small book: at 18x12cm it has the feel of a Gideon’s Bible, which I’m sure Nekrasov would find amusing. Sideways on and it’s hefty – running to over 500 pages. The five sections are taken from non-samizdat collections, privately published visual poems and unpublished poems that appeared only on a friend’s website. They are both varied and unified, presenting a clear and focused vision Nekrasov had for his work, which appears unchanged through and beyond the demise of the Soviet Union. That adds another dimension of weight to this brick-sized volume…