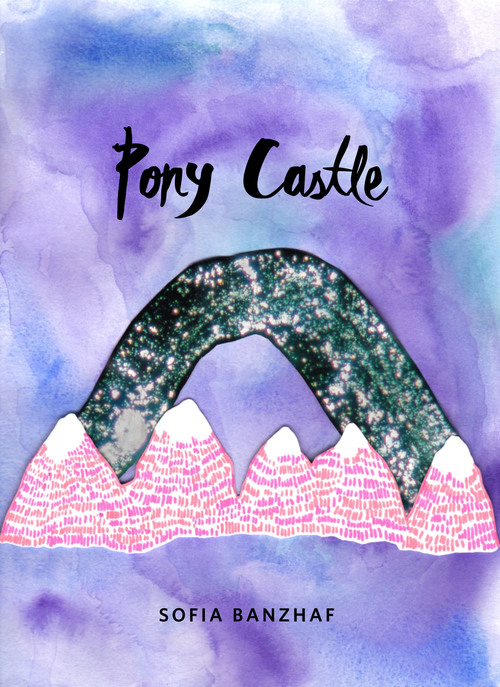

Pony Castle by Sofia Banzhaf

– Reviewed by Bethany W. Pope –

Sofia Banzhaf’s Pony Castle is a work of beautiful entropy that centres on a dark metamorphosis. Over the course of the novella we witness the nameless narrator’s slow dissolution into a flurry of drugs and sex. There are two central images; the plastic Barbie pony and the image of the butterfly emerging from the chrysalis. These two images are double-edged; in western culture ponies and butterflies are considered to be very ‘little girl’ things, but the narrator is not a little girl and although at least one of the butterflies has pink wings, they’re formed from a Rorschach-blob of smeared period-blood. As for the pony, the one referenced in the title is sweetly pathetic; it’s slowly shedding her pretty nylon mane.

The narrator is in trouble. Her brain is breaking, overwhelmed by self-loathing and the drugs she’s taken as a means of avoiding thought. She has a boyfriend, a second boyfriend, and an older man that she occasionally sleeps with. Banzhaf has developed a voice that is fragmented, annoying, and absolutely perfect for the character. Mingling uncomfortable insight with self-deception, the narrator engages in activities that she thinks she ought to enjoy while her real, lost self creeps in at the edges:

I am thinking about the colony of moths that has settled on my bedroom ceiling. I’ve been watching the larvae cocoon and after some time, a fully formed moth drops from the ceiling into my bed. I’m not sure what to do about it. The man is watching me, waiting for me to perform. What I feel like could be happening but isn’t happening at this precise time, although in some ways has started happening: I am cheating on my boyfriend and I am cheating on the boy that I am cheating on my boyfriend with.

Most of the narrator’s time is spent avoiding thought, avoiding anything that would force her to interact with what the rest of us would call the ‘real world’. This is not a new trend; apparently she’s been doing this for most of her life:

Mozart died from eating pork chops. The world is dangerous and my mother once told me that happiness comes from the heart, not the places you go and I say good, because I’m not leaving my room and I will draw circles in this notebook until my wrists break.

Ordinarily, refusing to give a name to a narrator is a sign of either laziness or pretention on the part of the author. That’s not the case here. This girl, this drugged-up, broken woman, is attempting to unmake herself. She is not aware that she is suicidal; the reader absorbs that knowledge through the text. This refusal of a name is one subtle side-effect of the death-wish. And in the context of this novella it is an extremely effective device.

It is typical of this narrator that she is totally unaware of how much of herself she has lost. Kurt, the jerky man she is having an affair with, gives her a bracelet to ‘help her break bad habits’ (an act of care that is totally lost on the narrator who doesn’t believe that anyone could ever hold positive feelings for her) and her mentally-ill French roommate moves out in an attempt at preventing her own relapse. The friend, Anita, who accompanies the narrator on her drug trips spends her paycheque, sells her jewellery, and then her body in an effort to keep up with her habits. The narrator is aware of Anita’s deterioration but has no mirror to scry her own in. Instead, Anita becomes her mirror:

Anita is throwing up in the bathroom just like old times, but this is new. She took too much, she should have known. I hum the melody to “Orinoco Flow” by Enya loudly so she can hear it and feel comforted. She’s moaning and muttering something. I open the bathroom door and she turns to me with red eyes and puke on her black velvet dress.

In the end there are no real butterflies; the plastic pony is taken, packed in a box by the French girl as she evacuates the narrator’s decaying life, and the narrator herself is still denying her chance at redemptive self-awareness. This novella is very short, a bare 47-pages, but it is incredibly effective at what it does. Its themes are too big to be comfortably compressed into the span of a short-story and the plot is too tense to stand to be stretched into a full-length novel. It’s the perfect length to read over the course of a half-hour commute, but rest assured that if you start it then you’ll be thinking about it for the rest of the day.