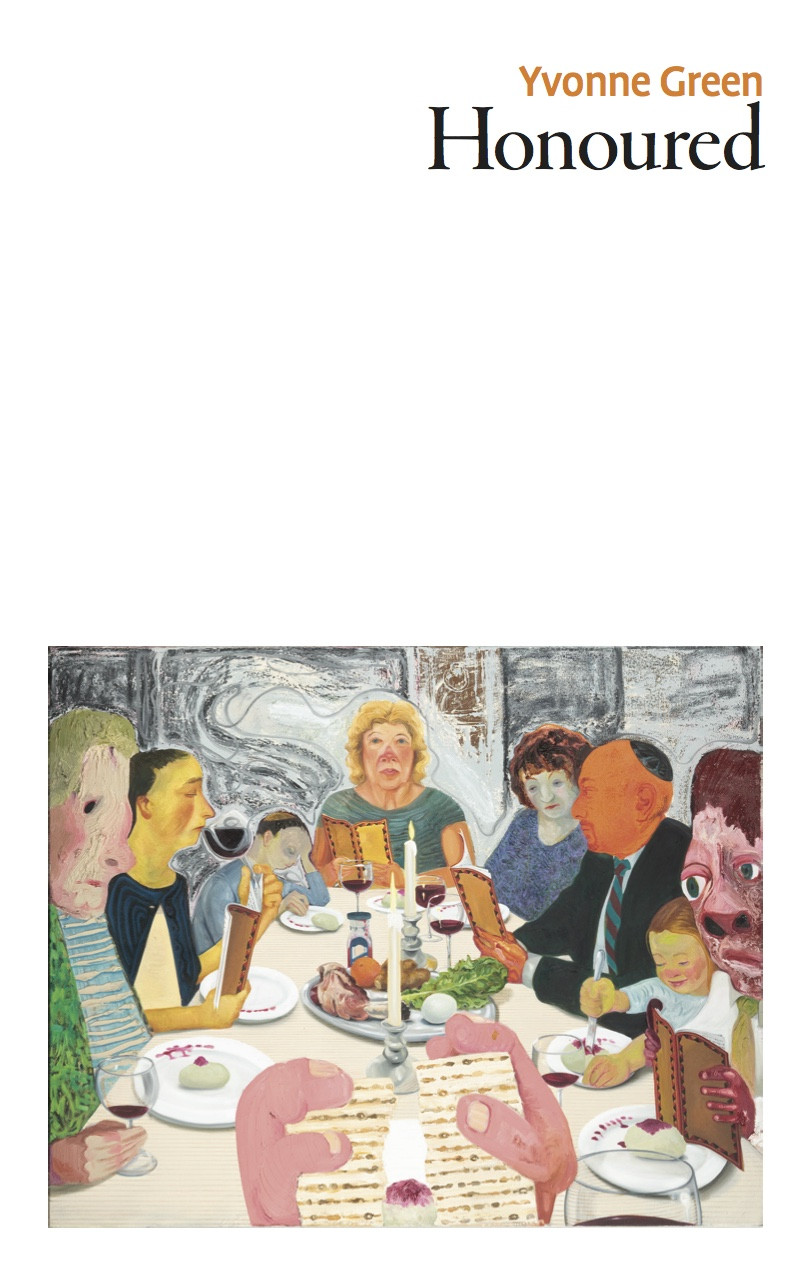

Boukhara and Honoured by Yvonne Green

– Reviewed by Angelina D’Roza –

Yvonne Green won the Poetry Business Book & Pamphlet Competition in 2007 with her pamphlet Boukhara, poems that focus on home, identity and heritage. These themes continue to run through her work. In the title section of Honoured, Green’s fourth book, “Advice” catches something of the collection’s cultural and linguistic complexity, embodied in the speaker:

You say learn my language,

forget your own,

it brings new ideas, possibilities,

gives you an alphabet you never had

as your mother whispered secrets

she’d learned from hers,

which she never understood.

This is an intricate set up – the mother possessing the secrets of an alphabet, passing those secrets on, neither of you understanding what they are or mean. Language contains more than communication: translation involves trying to transpose culture as much as words, which underpins the line “It brings new ideas, possibilities”. But why doesn’t the mother understand what she’s learned? Perhaps because of that second line: “forget your own”? That’s a big thing to say: that you should let go of your first words, the words you think in. Is the implication that you have to fully belong to this other language in order to – what? Free it? Be freed by it? As though your own language is trespassing in the new one. What do we lose when we forget our own language? In the last lines of the poem, this is answered, although the reader might not believe it – you lose nothing, gain everything:

There’re no questions you can’t answer, re-answer,

change your mind about

if you listen, fine tune, use my cadences,

don’t be afraid, you won’t lose yourself.

“You won’t lose yourself”: that’s what this poem comes down to. Many of the poems preceding this explore freedom, violence, oppression, of/against women, and language seems to play its part in this. If “everything’s a part of speech / and everything’s translatable”, then so is our identity. We are the language we speak. Whether or not we take this poem’s advice will determine who we are, what we think.

In Green’s pamphlet, the identity and translation of the speaker are central: “We speak English now and gratefully. / […] We have / translated ourselves” (“We Speak English Now”). Boukhara offers a life, and way of life, the impact of heritage on its descendents, often through first-person observation and experience. Even where the “I’ belongs to quoted speech, the distances between “you”, the speaker, the listener, are negligible:

‘My mother told me a long time ago

you can eat a mountain of salt with someone

and still you cannot know them.[…]

At our table we did not eat a mountain of salt.

Together we ate maybe this much.’

His hands and his mind’s eye reckoned outa mound from his belly to his chin.

In Honoured, the “I” is perhaps less prevalent, or maybe the view is more often panoramic. Observation is used to consider a breadth of potential identities, search the possibilities of empathy and dialogue:

Poles renovate London; swing picks

and hammers, tense strong backs,[…]

When this newest workforce goes

will the houses they build back homereplace the being there, that’s in the children

they’d sent, dainty, to our schools, libraries”(“First Generation”).

Or in “That Kind of War”:

We’ll change our clothes, hair,

food, learn the languagesof the women who aren’t free, the ones who are

and of those who will never be.

This collection has more distance, and the result is sometimes less immediate, but not less moving. It is intelligent and provoking.

The last section, Jews, takes in conflicts and landscapes that, I think, unpick reductionist political lines: “she’s trying to listen, watch, see the difference / between her enemy’s wife and her. Her child, / his, her grandchild, his, her mother, and his.” (“Arab Spring”).

This section moves towards the present out of historical events and figures, celebrates place, language and ritual through exile and excavation. “Sabena Spielrein”, for example, hiding her diary in the Rostov shul, railing “against a void” or “Korczak”, who set up a children’s home, writing to the British Consul to ask for napkins. Korczak and his charges die in Treblinka, so the line about these napkins, “they’d sent enough for generations to come”, becomes devastating. It’s hard to balance a line like that without pulling down the whole poem. I think it works because of the detail, which keeps the poem tilted towards the ordinary in extraordinary circumstances. These are poems about people rather than legacy:

We’re neither poems for you to fetishise

nor emblems of the murdered of the twentieth century,

we don’t hold all possibilities in our Talmudic minds

live burdened with the grief you want us to.

[…]

There’s no monopoly on suffering(‘Jews’)

Green writes in a clear, plain style that presents complicated ideas without the highfalutin weight of their own intrinsic difficulties, but also without simplifying them. These poems are like knots that look easy to unravel – until you try.