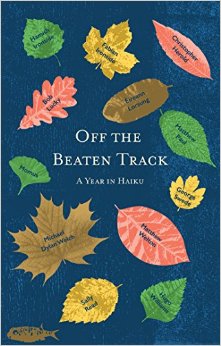

Off the Beaten Track: A Year In Haiku ed. by Boatwhistle Books

– Reviewed by Simon Zonenblick –

Off the Beaten Track purports to document a year in haiku, and is accordingly arranged into twelve poets with a month apiece, with a black and white illustration by a different artist for each section. The poets produced one haiku for each day of the month: half the featured poets had already published large numbers of haiku, while the other six were known for other verse forms, but new to haiku. This mix, the editors felt, would result in poetry both informed by the experimental style of seasoned haiku practitioners, and the ‘beginner’s mind’ that is traditionally considered an important element of haiku in a more literal, perhaps purer sense… So while this is a book of English language haiku, it is one that is indeed off the beaten track. This information comes as an Afterword, and might have helped me as a reader to make sense of some of the entries, which greatly differ in style and substance from what I have come to regard as haiku. But more on that later.

January is entrusted to Hugo Williams, and begins beautifully:

What we have here

is a gate in a wall

with its timetable of opening hours

But the “haiku” soon veer into a less meditative territory:

Not much chance

of getting away this weekend.

But wait, there might be

and a tone of intellectual humour and wit which is ill-at-ease in the context of a 17th Century Oriental verse form derived from Buddhism:

You’re writing things down

because you want to.

But suppose you don’t want to.

Do you drop things?

We drop things all the time

(this includes breaking them)

The second example above is positively obscure, and would surely be more at home in an anthology of surrealism or as part of a longer poem spoken in the voices of different characters. It does not really seem to embody the essence of haiku in any recognisable sense. Nor are many of Williams’ offerings particularly evocative of January, from whichever viewpoint that month’s significance is interpreted.

I find myself in the strange position of defending traditionalist interpretations when I demur from pieces such as:

Never mind what you’re thinking about

its what you’re not thinking about

that counts

not because I favour an inflexible approach to poetry – I don’t – but because haiku itself is not inherently flexible. I was schooled in the form by the great Keith Coleman, a veteran haiku poet who counts among his achievements translations of Basho, and prolific publication in journals such as Presence and Blithe Spirit; he rejected the prevailing “rules” about using certain numbers of syllables (which may make rhythmic sense in the Japanese in which haiku were originally composed) in favour of the founding values behind haiku. While I believe it is perfectly laudable to invert verse forms, create new ones from old, write in “neo” or related styles, or dispense with regulations altogether, I feel that to take a form like haiku, and use this as the name of the particular kind of poems you are composing (as opposed to simply “short poems”) does imply a moral obligation to abide by the precepts of that form. What differentiates haiku, with its essential traditions of reflecting two separate images juxtaposed by a kirji (“cutting word”) , from similar forms of poetry such as senryu is surely its detachment from personal, or personalised, observation and opinion, yet quite a lot of the poems in Off the Beaten Track do not adhere to these precepts. The piece quoted above reads like an aphorism from a fortune cookie, or the sort of thing sometimes posted on facebook, and is presumably intended to be profound. But it is surely more of a philosophical argument than a piece of haiku poetry.

Williams does, however, return to the presciently observational – and the poetic – with lines like:

The natural world

is shivering and shaking

as if it could see into the future

Febaruary’s haiku come courtesy of Hamish Ironside, and include such deceptively gentle depictions as:

cloud smothering sun…

secondguessing

my subconscious

my only query being why the poet chose to combine secondguessing as one word – surely the meaning of the phrase is more clearly underlined when appearing as two distinct words.

There are several true gems:

showing them

how it’s done –

the mason’s gravethe surgeon’s wink

just before

I’m undersmall-town charity shop –

I tell an old lady

I’ll never be back.

and the following jest:

proofing a text

about mindfulness

without reading it

Earlier, I berated the inclusion of witty jokes as distinct from true haiku, and I still maintain that even the above poem says nothing about the month or season it is written in, but it posesses a certain self-deprecating humour that I can somehow imagine being employed by Basho. The same ability to have fun with haiku is found in:

a fuzzy tannoy

rendered dub poetry

by the busker’s reggae

while compassionate poignancy is delivered in:

long-distance-call –

years fall away

for a few secondsa wren

explores the forest

of a single pine

In March, Matthew Paul delivers various thought provoking haiku which sometimes rest too much on name association or worldly knowledge. He does, however, serve up some delightfully tangible and plausible images:

over the railway

two ducks synchronize

their rapid descentnight rain

the warmth of her kisses

on my spine

In April, Michael Dylan Welch provides a slightly ironic feel:

pinker

against the blue

graveyard cherry blossoms

with a lovely twist of wit which, like that of Hamish Ironside, somehow feels appropriate:

national haiku day –

where’s a scrap of paper

when I need it

Matthew Welton‘s poems for May also experiment with ironic or contrasting images:

apricot tree

blossom the colour

of lichen

sometimes verging on the eerie or macabre:

birdless back yard –

too early to be

this awake

I do not intend to trawl exhaustively through the remainder of this collection, but it is sufficient to say that if the succeeding months pursue any sort of seasonal narrative, it is too frequently interrupted by irrelevancies that render it somewhat inconsistent or incomprehensible. For example, on a random page for October, we have:

They talk about going

To New York

But will probably stay in Berlin.

and

He failed in art because he was

Too proud

To suck Klaus Biesenbach’s cock.

The more I read and re-read this collection, the more I grew convinced that the vast majority of the poems would easily qualify more as senryu than as haiku, and the more it felt apparent that the sequencing, perhaps intentionally, does not particularly reflect a linear or seasonal approach to chronicling a year through verse. But whatever its pitfalls or anomalies, Off The Beaten Track contains a considerable number of truly enigmatic, moving and original pieces, which work as poems regardless of what name is given or not given to their supposed genre, such as :

the longest day

a tugboat tows a barge

towards the rising moon(Christopher Herold – June)

rainy season chill

policeman on the edge

of the demonstration(Bob Lucky – September)

and the beautifully surprising verses of Éireann Lorsung, whose December haiku round off the collection:

A bulb tossed months ago

in an empty bed

has two bright leaves