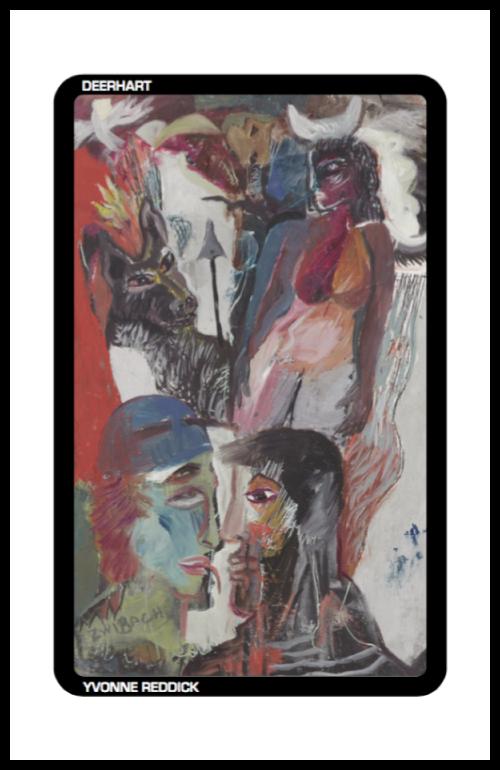

Deerhart by Yvonne Reddick

– Reviewed by Grant Tarbard –

I am writing this review in the corpse of the night, so let’s rip through it: Yvonne Reddick’s recent research focuses on British environmental poetry, working on a book-length study of Ted Hughes from an environmental perspective. Deerhart is filled to the gills with rock pools, life in miniature, rutting stags, and the ghost of ‘The Thought Fox’:

I imagine this midnight moment’s forest,

Something else is alive

Beside the clock’s loneliness

The first poem, ‘Devil’s Thunderbolt’, feels like Heaney-by-the-Sea, touring a secret world, the first layer of the earth beneath:

At a cliff’s foot

I hunt ammonites

in fissile layers

of flaky slit-beds.

I call it Heaney-by the-Sea as it reminds me of Heaney’s ‘Digging’ – the spade as pen, the belemnite as pen:

But a belemnite

tight as a rifle bullet,

finds me.I turn it between fingers.

Thick and unwieldy

as the graphite-tipped stub

that rounded my first

laborious letters.

Reddick explains that in Whitby dialect, the belemnite is referred to as a ‘devil’s thunderbolt’. The first line of Trilobite screams “read me!”

Curled like a human embryo-

Who could resist?

Curled like a human embryo-

compound eyes blank with mineral dreams.

Its frail armour still bracedto endure the undersea sandstorm.

Blank with mineral dreams, yes, that suits perfectly. A trilobite’s eye is like a chain mail strawberry, ripe pods of blackness. The poem is to the point, on message you could say, but that message is delivered with aplomb.

‘Sylvia’s Plait’ is a forlorn wire across the ethereal plane to Plath. The poem details her hairstyles down the years and correlates them to her mood at the time: breezy at the beginning, haunting at the end, as one might expect.

You pick through boxes of her oval writing

and stumble on the casket that holds her hair.

Warily, you lift the lid.

In the penultimate stanza the words rip through the post like a pack of angry dogs:

in 1962, when something came undone.

That winter, her hair hung lank, untressed.

Right next to it is a poem dedicated to Hughes, ‘Lined Notebook, Slight Foxing’. The muse here is Hughes’ spirit, suspended over Reddick, whispering in her ear:

I can hear you

through the page in front of me:

If you’re going to do summat, do it good.

The muse theme continues with

You cast bait for words

while raindrops slur the ink

Beautifully put. Although she’s talking about Hughes in this instance, he could be easily replaced with the poet herself. Poems about a death aren’t usually handled with this subtlety:

Now you’ve gone to ground

among these speckled leaves

where the dogs can’t dig.

This is a graceful collection. Anyone who’s not keen on nature poems need not fear; there is much here besides the usual trope of trout. You can watch the evening grow old with this pamphlet – it is comforting. The night has grown into morning. I’ll leave the last words to Ted Hughes, the revenant of this work:

The window is starless still; the clock ticks,

The page is printed.