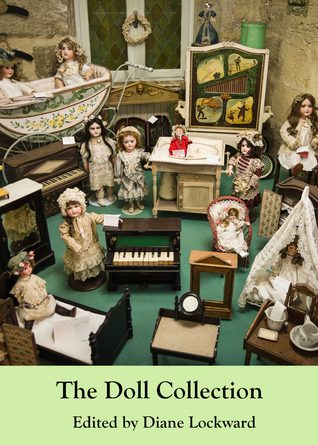

The Doll Collection edited by Diane Lockward

-Reviewed by Deirdre Hines-

This anthology celebrates the representation of dolls in present day American poetry, in all their diversity. Of the eighty-eight poems that chart the compulsion with dolls, each one stands against the blandly cosmopolitan standards of dominant media corporations. The different voices, styles and language of each poet reflect the truth that in order to be universal, good writing must be local, rooted in a specific culture. Dori Appel’s ‘Raggedy Anns’, Jeanne Marie Beaumont’s ‘journey with a dream doll’, Paula Bohince’s paper doll likenesses of the Dionne quintuplets, Luanne Castle’s marriage doll, Caitlyn Doyle’s elegiac reference to Egyptian stone dolls, Ann Fisher-Wirth’s elemental rat doll (echoes of Ted Hughes here), Jessica de Koncik’s golem of memory, Susan de Sola’s ‘Frozen Charlotte’, Gail Fishman Gerwin’s elusive ‘Sparkle Plenty’, Nicole Cooley’s pregnant doll, Susan Kelly De-Witt’s ekphrastic cloth doll, Adele Kenny’s emblematic Ginny doll, Denise Low’s histories told through a Delaware dance doll, Mary Makofske’s yearned for ‘Bambi’, Lori Desrosiers ‘The Room at the House in Croton’ all entrance and redefine the doll. There is a doll with magically growing hair called Velvet, an acorn doll, potato head doll, apothecary doll, Red Riding Hood flip doll, a cyborg, a Dresden China boy, Matryoshka dolls, puppets, ballerinas, teddy bears, Barbies, and a Madame Alexander Amy doll, and they populate these poems as a unifying symbol. They too, serve as routes to a new understanding of childhood, rites of passage, identity, worship, the illusory nature of reality, the sexual politic, class relations, changing fashions, sexual fantasy, paedophilia, pupaphobia, venustraphobia, auto da fes and gender construction.

There are many poems in this collection which stun either through their expert handling of form, or with imagery that haunts the reader long after the book has been closed. David Trinidad’s sestina ‘Playing with Dolls’ subverts beautifully the straitjacket of norms in what is a tightly controlled form. This is a clever move, as it makes the speaker’s transgressions all the more focused for the reader in lines such as these:

It isn’t normal!”) faded as I slipped Barbie’s

perfect figure into her stunning ice blue and

sea green satin and tulle formal gown…..

His closing envoi could have been a little more tightly reined in, but he more than succeeds in redefining playing with dolls. Barbies appeared in 1959, and how the socio-political norm affects perceptions of relationship and class division is well handled in Julie Kane’s ‘Alan Doll Rap’. The humorous twist in the final lines “Where’s that giant hand/ used to make him stand/ used to make him walk?’ echoes the frustration of many women everywhere, and is also a clever play on the metapoetic.

Lauren Camp’s ‘The Model of Perfection’ brought me back to my own childhood. The nightly ritual the speaker of the poem’s sister enacted: her “whispered good night/ to dozens of pursed lips” in

“the eyeful dark” haunts. In many ways, this anthology is full of eyes. Susan Elbe’s ‘Colleen Moore’s Doll House’ on display in the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago Illinois is what the speaker of this poem falls for, instead of the suspended octopus, or jars with fetuses. The “Field-trip voyeurs” peer through its “incandescent windows” at opulent miniature furniture and at “ …tiny books, some first editions, some handwritten, older than a century”. The tour de force of this poem lies in the stark contrast between the doll’s house and the speaker’s own home, with its chilly bedrooms without “a bedspread made of golden spider web”, and in how the speaker with eyes “occult as oil-smudged isinglass” is steadied by the imagination, that she learns “only opens with the word.”

Doll culture is much much more than doll as object, as this anthology excels in showing. The doll embodies cultural histories, and are more akin to Joseph Cornell’s memory boxes than anything else. The doll also embodies emotional histories and traumas. One of the most thought provoking lines in this collection is from Roberta Feins’ ‘Metal Doll’ “Who is this can injure me so easily?”

The sheer individualism of Jane Ebihara’s child “content/alone with my child” endeared me to her immediately in ‘In the Milk House.’ Ann Fisher-Wirth’s stunning prose poem ‘Snake Ladies’ brings doll culture into the numinous, the ritualistic and the transformative. I loved it.

so we slithered to the toy shelves

and chose four animals, mine was my teddy bear

Fuzzy, my little sister’s was her bear Kathy, our friends had

Tigger and Roo, and writhing in the darkness, we held them

to our nipples.

Richard Garcia’s ‘Doll Heads’ is unsettling and visceral. The metaphor isn’t as simplistic as it first appears to be. On one level, they are symbolic of present day beheadings by insurgents, on another, as they drift in on the tide of human affairs, they are the flotsam and jetsam of the senseless loss of life in the wars we wage, decisions made by heads not hearts. The shadow side of doll culture, also explored by Jendi Reiter in ‘The Fear of Puppets and the Fear of Beautiful Women’, is written in couplets that steadily chill until the final terrifying line “the fist of the one who holds you on his lap.” Our love of dolls is a bulwark against grief and loss, as Jessica Piazza’s sonnet ‘Pediophilia’ depicts. A dead daughter’s room is filled with a “thousand eyes that cannot shut”. A solution to this shadow side is offered by Hayden Saunier in her ‘Flip Doll: Red Riding Hood’, with the closing line “You’ll have to save yourself”.

With this fascinating collection, Diane Lockward has succeeded in editing an anthology that places the doll centre shelf in the poetic canon.