Muses and Bruises by Fran Lock & Steev Burgess, ed. by Mike Quille

– Reviewed by Becky Varley–Winter –

This collaboration – featuring poems by Fran Lock, and collages by Steev Burgess – is gorgeous, both in the sense meaning ornate or beautiful, and the gorge rising in the poet’s throat. Muses and Bruises contains two poetic sequences, one responding to the Muses of Greek myth, and the other following two ‘Rag Town Girls’ as they explore the shivery, resilient clublands that Lock’s work often draws on.

Lock opens with a passionate defence of the right of ‘marginalised’ readers and writers to the full range of literature, the full range of cultural expression:

I came to poetry alone, late, and by chance. My first feeling at having found this beautiful, radiant thing was a mixture of exhilaration and relief, rapidly followed by a massive sense of blind and burning rage that something so essential, so sustaining, something so rich in sweetness and meaning had been kept from me. […] I love poetry, all poetry: the Lais of Marie de France, Chaucer, Milton, Blake, Clare, Keats, Yeats, Fiacc, Plath, Brookes, all of it. […] I was once told that my writing was inauthentic because working-class women don’t think or speak that way. Bollocks. I am a working-class woman, and I do write and think and speak this way.

The nod to Keats feels apt, as Lock’s style reminds me of Keats advising Shelley that he should ”load every rift’ of [his] subject with ore‘. Every line is crammed with raw invention. When Lock writes in ‘Euterpe, 1953’ (the muse of music and lyric poetry) ‘these village women envy / me my revels,’ she sounds a lot like Puck, and she often evokes a Shakespearean sense of the poem as a stage that her words cavort across, using plenty of alliteration and internal rhyme. For example, in ‘Melpomene’ (the muse of tragedy):

[…] I am sleazed in

the green of The Land, raining down

her birdsong in blows. The dubby

crush of my keening does his head in.

I sink kisses into screams like pushing

pennies into mud. And he says he is done.

From the wordy murk of my loss come

lanterns and daggers, and I am my country:

mean, gutless and Medieval; a dread

mess of battlements and spoils.

I’ve heard her read some of these poems, but they come across even more clearly on the page, with time to absorb each detail. The sound works on me first, then I look up new words, such as poítin, an Irish alcohol (that sounds a bit like poison); isinglass, a substance from the stomachs of fish, used in beer brewing; skirl, meaning ‘to give forth music’; sovvies, rings with a mounted sovereign coin on them; a farrago, a confused mixture; luciferase, the enzyme that causes bioluminescence. I want, rather than need, to look them up, and they create the effect of a cave of wonders, the poems being full of the pleasure of their own making.

Muses and Bruises is beautiful – the ending of ‘Melpomene’ (which you can read in full here) is especially, breathtakingly good – but it is also angry, siding firmly with the experiences of transient, migrant, traveller and working class women. In her note on the ‘Rag Town’ poems, Lock informs us that International Women’s Day used to be called International Working Women’s Day, and she places class politics at the centre of her feminism. In ‘Rag Town Girls Don’t Want To Be In Your Shitty Fucking Magazine/Anthology/Stable of Wanky, Middle-class Poets Anyhow’ she writes:

[…] The world is not something to traverse,

but something to survive. To keep us on our toes the city varies its monsters,

but sex keeps harping its long, fatal theme. […]

While this book wears its politics on its sleeve, there’s little sense of preaching to the converted; Lock writes as though she wants to grab the face of every reader and pull it towards the page. Her work is experienced and persuasive, and she describes her Rag Town Girls with familiar tenderness, as they ‘Slow dance in odd socks’.

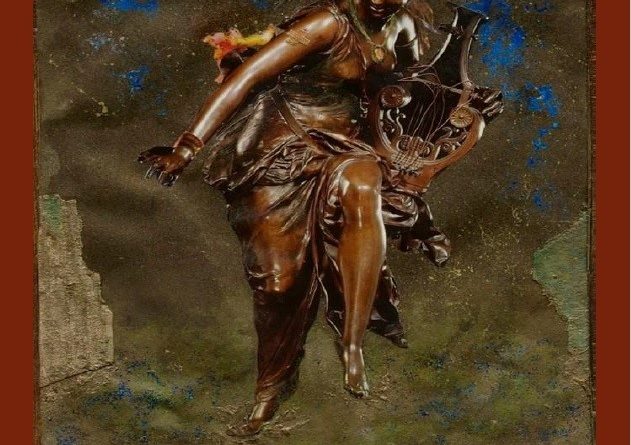

Every poem is accompanied by one of Burgess’ collages, which are extremely beautiful, moving from the golds and pale blues of ruined churches into increasingly vivid, ‘acid house’ colours in the Rag Town section. They feel Blakeian in spirit, and fit the themes of Lock’s poems without being merely illustrative of them, as Burgess notes:

I found that the solution was to represent the atmosphere, and bring the muses to the streets of modern day London (Camden town in particular) where I live and Fran once lived in a crumbling Georgian squat. I wanted to evoke the damaged walls of a squat, with naked wires and broken plasterwork painted with my pictures, painted over as people were wont to do as well.

In short, this book feels like an equal partnership between poet and artist, and their collaboration is quite dazzling. Lock’s themes remind me of Rebecca Tamás’ and Sophie Collins’ poems on witches and saints, putting her in good miraculous-feminist company, and I’d recommend this particularly strongly to anyone who enjoys their work, but it retains a style of its own. I came to Muses and Bruises already admiring Lock’s poetry, but was still surprised by just how much I loved this book, i.e., completely.