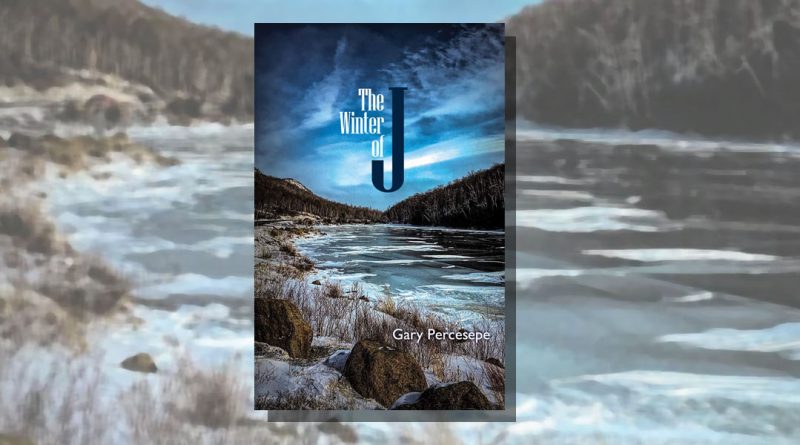

The Winter of J by Gary Percesepe

-Reviewed by Alina Stefanescu-

The Winter of J, a chapbook by New World Writing associate editor Gary Percesepe, resides firmly in the camp of broken hearts, the chapel of wist, the porch of pain and sorrow.

The poet leads us through a six month relationship with J, it’s beginnings, ending and residual burn-marks. The first section Meeting begins in ‘The Boat’, a prose poem about meeting J, the loose ends of exes and past lives between them, but it is the next poem ‘December 17’ that alters the tonal landscape. The lines are long, but disciplined, broken by lineation:

When she finally arrived it was like a cello playing inside me.

I became interested in what I might become. In a candlelit room

of North Pole elves and children’s notes, she whispered, Stay.

Outside, the furious season, blowing. Faith is a hunger. It took

me a long time to see my life, I’ve stood on top of myself, looking.

Inside her felt more like home than a visit.

The poem ends with the claim: “I’m saying everything I wanted was in that room.” ‘Blizzard of Two’ brings us closer to J, into waiting, where a storm is used as a vehicle to convey the tension and sense of foreboding between two lovers at the brink of something big. It is exultant, hoping towards lightning. In “that winter”, we learn of her “twitching bunny nose”, the eros of “newly sexed hair / disturbing the air”, ‘White Room’ ends on this erotic, tangled note.

The next section Break-Up begins with ‘Buffalo’, the place from where the narrator finds himself looking back, suffering “from the fear / of what already happened.”

‘Say Her Name’ throws us into the thick of it, beginning “Bodies matter, the way they break / open, the way fluids spill.” The narrator swivels between dream and meditation, looking for an answer to why he is here and not with J. In this interior monologue, he brings metaphors to bear on decoding, from Helen of Troy to Rilke’s terrible angels to Keat’s urn. The narrator surrounds himself with the arsenal of grief in poetry. In the first stanza, the words move quickly, a loose web of associations, a hallmark of the grieving mind:

I’m here to

document the disease of naming what we want and never

wanting what we get, the way she has become both the poison

and the cure. She is one hundred countries I’ll never

visit, ten thousand islands where like Crusoe I’m stranded.

Why am I here? I am here to learn again the calculus of

loss, the difficult arithmetic of the recalcitrant heart.

The second stanza makes a sort of music through repetition and similar pacing. The construction of the poem is powerful and effective:

Every angel is terrible.

All bodies know how to open, one needn’t choose;

any wild animal may enter any open door. Why am I here?

I am here to learn again the calculus of loss, the difficult

arithmetic of the heart.

‘My Old Jeep’ is a long prose poem, or a flash creative nonfiction divided into sections. It is a ride in the narrator’s Jeep to experience how this moving space has been colonized by the memory of J. And “anywhere”:

the glitter of her teeth

will become the lights

of the city you left.

This ardorlogue, or diary of a love affair, is almost over. The last section Memory is framed by an epigraph from Albert Camus about the “invincible summer” he discovered inside himself during the dead winter. Remembering is the lover’s eternal task: “as in death our deeds follow us” the narrator says in ‘new world’. The new is some variant built from what’s past and the variation holds all the origins inside it. Percesepe watches the women known “only from their leavings” make their way through the world in ‘Just Wrong’. The lovers unfreeze and mingle like water in a lake, the solidity absent, the liquid present.

The final poem, ‘Another Poem That’s Not About You’, shows the poet at his best in a block of lyric prose, its brave absence of elegy, its lack of recrimination: “The mystery of beginning, resumes.”