In January 2021, the Poet’s Hardship Fund UK was set up for charitable donation, by Alex Marsh, Tom Crompton, and Dom Hale. The fund printed its first issue of the associated pamphlet series Ludd Gang in February 2021, the second followed in April, the third in June. The fund has helped support many poets in precarious situations and needs with donations from inside and outside the poetry world to continue.

Each issue comes with a strongly stated epigraph. In the first issue, printed in red, ‘official language’ is cast as ‘the inheritance of bastards.’ It is announced that the putative hero of the poets represented in these pamphlets, ‘King Ludd’ may even ‘lose his sceptre.’ King or General Ludd refers to a weaver from Leicester, Ned Ludd (b.1799), who came to be seen as the symbolic leader of the Luddite protests in Nottingham in 1811, that took aim against the automation of weaving through investment in textile machinery. The organisers of the hardship fund believe: ‘Poetry is an apparatus, the threat of something moving on the way.’ They don’t want this fund to be the centre of administering poetic support, but one example amongst many of progressive reforms that disregard ‘executive truth.’

Poets are selected for each anthology as though donating their work in solidarity with the fund. There is no editorial oversight exactly which has the paradoxical effect of only making the choices seem more deliberate, more significant. In the issue from February, Maggie O Sullivan develops a line from Etel Adnan: ‘one of the animals of this earth.’ Tom Betteridge pivots through various ‘positions’ looking to remember that ‘movement makes sense.’ Lotte L.S. aims to ‘bring into convergence/three activities of being-what I’d seen, what I’d read, what I’d drawn’, making ‘an addressed constituency’ from ‘paced circles of a monthly rolling tenancy.’ In ‘Death of BAME’, Zibby Ibn Sharam tackles ‘the cop in your head’, the internalised ‘saboteur who criticizes you’, making BAME individuals think ‘you ain’t worth anything.’

These are not simply lockdown poems, but works that try to register the political iniquity that becomes more obvious during a pandemic. In the fifth part of Glacial Decoys, Luke Roberts imagines the pandemic as the confirmation of successive crises that have held poetry back: ‘I start explaining my theory: that the 21st Century still hasn’t begun. All we’ve hard for twenty years is decades. In the long chain of catastrophes, stuck sometimes up to our ankles, our necks, our waists, we were doing our best to start it.’ Sarah Crewe repudiates the class politics of Eliza Doolittle in an effort to refuse ‘to forget our own language’, amidst the weak forms of ‘praise & opportunity’ that mean ‘payment methods’ are ‘not a sinecure.’ The last poet in the first issue, Geraldine Monk, writes of ‘Songings & Strangerlings’: ‘In the land of strangers be/lost be lost/in me.’ The word ‘strangerlings’ captures the tension between the new and the unfamiliar that is perceptible in each issue of Ludd Gang.

Together these three pamphlets call for poetry to be recognized as work. The contributors are all allies of Peter Gizzi linking poetry and work: ‘when I said work, and meant lyric.’ This is the opposite of elevating poetry above other forms of work. Rather, the implicit assertion of the Ludd Gang pamphlet series is that poetry must be understood and rewarded as work similar to and useful as any other. Elsewhere, in another pamphlet uniting similar poets, no relevance (2020) that is available from red herring press, one of the Ludd Gang contributors, Lotte L.S. warns of the ‘dangerous liberalism (too often disguised as militancy) of trying to claim that people don’t need books like they need food, housing, work, warmth.’ no relevance is available here: https://redherringpress.bigcartel.com/product/no-relevance-1

The Poet’s Hardship Fund has already received some high profile attention, especially, in an essay by Helen Charman in The White Review, that makes a very useful comparison of the fund to poetry awards: https://www.thewhitereview.org/reviews/holding-the-room-on-holly-pesters-comic-timing/ What emerges from this comparison is that the Poet’s Hardship Fund is seeking a more equitable model for a trade union for poets than is currently achievable by the Society of Authors and the prizes it administers for writing. Charman is also featured in Ludd Gang 3, writing a ‘Failed Address to my enemies’, a poem that looks forward to a time when protest ‘marches’ are free of ego: ‘have stopped or rather they’ve/no longer a need of you […] I hope that nobody ever again/has any need of you.’ The Poet’s Hardship fund explains on its website that for those wishing to make a request for financial support, of up to 50 pounds a month, that: ‘The money doesn’t have to be for a project or a book; you’re a poet if you write poems. That’s it.’ The fund is free of reciprocal commercial expectation, or potentially, exploitation, which makes it so different from most poetry awards. Full details of the fund are available here: https://poetshardshipfunduk.com/. The fund is permanently open to donations.

]]>I’ll be the first to admit I haven’t stayed at Sabotage for as long as I expected to. However, if the last two years have taught any of us anything, it’s that sometimes things work out a little differently to how we expected, and I think this is just one of those times. There’s a big old writing world that I want to dive head-first into, and I know deep down that Sabotage Reviews deserves a fresh face at the helm – and that Heddwen is most definitely perfect for the role.

The director@sabotagereviews.com email is still live and kicking, but it now belongs to Heddwen so please do make sure that all future correspondence is marked accordingly. Heddwen has my personal email so if anyone needs to contact me, she’ll be able to put you in touch.

I’d like to thank everyone who has guided me through, worked with me, and generally had a good old laugh with me over the last four years. It’s been a blast. But I can’t wait to see what happens with Sabotage Reviews next.

Stay safe and keep making beautiful things.

Charley x

]]>Congratulations, again, to all those who were shortlisted this year and, of course, to our winners, who we can now reveal…

Best short story collection

The Evolution of Birds by Sara Hill

Best spoken word performer

Joelle Taylor

Best magazine

Butcher’s Dog

Best literary festival

Leeds Lit Fest

Best novella

Crossing the Lines by Amanda Huggins

Best poetry pamphlet

Lemonade in the Armenian Quarter by Sarah Mnatzaganian

Best regular spoken word night

Verbose (Manchester)

Best spoken word show

Becoming marvellous by Cathy Carson

Most innovative publisher

Victorina Press

Best reviewer of literature

Josie Alford

Best collaborative work

Same But Different by Katrina Naomi and Helen Mort

Best anthology

81 Words Flash Fiction Anthology (Victorina Press)

Once again, a thank you to all. There are big things ahead for Sabotage Reviews so do keep in touch, and keep connected with our new Managing Director, Heddwen, will be rolling out her plans shortly.

]]>Note: I have endeavoured to provide links to relevant websites and purchases pages. That said, some artists and organisations can be harder to pin down than others and I’m also aware that preferences may have changed in terms of what information is being shared and promoted here. If you would like your information to be edited somehow, please do email me at director@sabotagereviews.com.

The form for the second round of votes is now available HERE.

While you’re here, why not take a browse at our accompanying festival line-up? All of our events will be taking place online this year so they’re easy to attend, and we’ve tried to collate a programme that caters to a wide range of needs and interests. The listing is available just HERE.

Best Short Story Collection Shortlist

- Fauna by David Hartley

- The Evolution of Birds by Sara Hill

- 100neHundred by Laura Besley

- No one has any intention of building a wall by Ruth Brandt

Special mention to:

- Only About Love by Debbi Voisey

- Dreaming in Quantum and Other Stories by Lynda Clark

- I Am the Mask Maker and other stories by Rhiannon Lewis

- The Map Waits by Sharon Telfer

Best Spoken Word Performer Shortlist

Special mention to:

- Jasmine Gardosi

- Ilaria Passeri

- Elizabeth McGeown

- Kathryn O’Driscoll

Best Magazine Shortlist

Special mention to:

- Ellipsis Zine

- Finished Creatures

- Streetcake

- Ink, Sweat and Tears

Best Literary Festival Shortlist

Special mention to:

- UniSlam

- Ledbury Poetry Festival

- StAnza

- Flash Fiction Festival

Best Novella Shortlist

- Crossing the Lines by Amanda Huggins

- Kipris by Michelle Christophorou

- How to bring him back by Claire HM

- Hairy on the inside by Tracy Fells

Special mention to:

- The Listening Project by Ali McGrane

- What will says by Lynne Buckle

- Taking flight by JT Torres

- Small things like these by Claire Keegan

Best Poetry Pamphlet Shortlist

- Lemonade in the Armenian Quarter by Sarah Mnatzaganian

- If All This Never Happened by Vicky Morris

- Pneuma by Faye Alexandra Rose

- Weeding by Jess McKinney

Special mention to:

- I am a Spider Mother by Flora Cruft

- The Kidnapping of Self-Kindness by Chris Singleton

- My Name is Mercy by Martin Figura

- May We All Be Artefacts by Chloe Hanks

Best Regular Spoken Word Night Shortlist

- Verbose (Manchester)

- Sayin? (Manchester)

- Fire and Dust (Coventry)

- Flash Face Off (Online)

Special mention to:

- Blue Balloon Theatre (Manchester)

- Tonic (Bristol)

- Flight of the Dragonfly (Online)

- Switchblade Society (Manchester)

Best Spoken Word Show Shortlist

- Turtle by Broccan Tyzack-Carlin

- Outlier by Malaika Kegode

- Dancing to music you hate by Jasmine Gardosi

- Becoming marvellous by Cathy Carson

- How to be a better human by Chris Singleton

Special mention to:

- I am 10,000 by Harry Baker

- Lady Ilaria’s Drawers by Ilaria Passeri

- Dry Season by Kat Lyons

- Bold by Nathan Evans

Most Innovative Publisher Shortlist

Special mention to:

- Fawn Press

- Broken Sleep Books

- Fairlight Books

- Fair Acre Press

Best Reviewer of Literature Shortlist

Special mention to:

- Melissa Todd

- Dzifa Benson

- Vic Pickup

- Laura Besley

Best Collaborative Work Shortlist

- Offcumdens by Bob Hamilton and Emma Storr

- GenderFux by Jem Henderson, Jonathan Kinsman, JP Seabright

- Eat the Storms convened by Damien Donnelly

- Same But Different by Katrina Naomi and Helen Mort

Special mention to:

- The Candlelit Sessions produced by Kathryn O’Driscoll

- First Line Poets Project

- The Dirigible Balloon

- The Conversation by Jo Burns and Emily Cooper

Best Anthology Shortlist

- 81 Words Flash Fiction Anthology (Victorina Press)

- Elements: Natural & The Supernatural (Fawn Press)

- Snow Crow (Ad Hoc Fiction)

- Songs of Love and Strength (Mum Poem Press)

Special mention to:

- Hit Points: An anthology of video game poetry (Broken Sleep Books)

- Ten Ways the Animals Will Save Us (Retreat West)

- The Weight of Feathers (Retreat West)

- What Meets the Eye? The Deaf Perspective (Arachne Press)

Thanks again to everyone who voted. If you’d like to cast you in this second round of voting, you can access the voting form here.

The 2022 winners will be announced at a LIVE awards ceremony taking place at the Library of Birmingham on May 14, 2022. Tickets are available NOW for anyone who would like to come along to see our winners announced, and to network and re-connect with new and long-standing literary friends. The ticket purchase page is available HERE.

Warm wishes,

The Sabotage Reviews team!

]]>Please read the instructions carefully to make sure your vote is registered.

The voting form is now available here.

To add to that excitement, we’re also delighted to announce that tickets to all festival events are now available too. Everything will be online this year – although the award ceremony proper will be live and in Birmingham – and all tickets are just £5. You can find the full programme, including direct links to ticket purchasing, by clicking here.

If you have any problems, questions or queries relating to the festival or the voting process, please do email Charley at director@sabotagereviews.com.

]]>The programme is available in full below, including links to the relevant pages for ticket sales. If you’d like to take part in the voting element of the Saboteur Awards Festival 2022, the voting form can be accessed now by clicking here.

Monday, May 9: A publishing panel featuring Isabelle Kenyon (Fly on the Wall), Aaron Kent (Broken Sleep) and Scarlett Ward-Bennett (Fawn Press). Our three industry experts will be talking with transparency about their respective experiences of establishing independent press companies, all of which have a strong ethos and mission statement at their core. Following the discussion, Isabelle, Aaron and Scarlett will welcome questions from attendees about the realities of getting work published and liaising with publishers in the independent world.

Tickets for this event are £5 and they are available now by clicking here.

Tuesday, May 10: An evening of ecopoetry from the edge with Kinara. Kinara (meaning an edge, shoreline or border in Hindi/Urdu) is a collective of women poets with inherited histories of migration and South Asian identities. Members include Anita Pati, Gita Ralleigh, Rushika Wick, Sarala Estruch and poet and translator Shash Trevett. With shared experiences of global migration and colonialism, our readings will trace links between colonial pasts and post-pandemic futures of climate crisis and global instability. The collective aims to explore how a truly global ecopoetry might include overlooked voices, from the Chipko movement in 1970’s India to the present day. Each poet will read for up to five minutes, placing their own work in the context of a global approach to the climate crisis and expanding on how their own histories have shaped and generated this work.

Tickets for this event are £5 and they are available now by clicking here.

Wednesday, May 11: Christina Wilson will facilitate a Writing for Wellbeing workshop on the theme of compassion and community, as part of her doctoral research. The workshop will put into practice Christina’s research about accessibility and inclusivity, gathering feedback from participants to contribute to the development of a methodology of inclusive practice for literary festivals. Focusing on curiosity about writing and expression, the workshop will be open to new and experienced writers; there will be no pressure to create ‘polished’ pieces of writing. Workshop participants will be invited to write from a series of writing prompts, including poetry and images, exploring times we have felt welcome, and how we might connect with ourselves and welcome each other into a writing/festival space. Christina will facilitate the opportunity to write a collaborative poem that will reflect on the feeling of welcome and community within the writing workshop.

Please note: Tickets for the workshop will be limited, particularly in comparison to other events, and all participants will need to sign a consent form ahead of taking part. This is due to some of the results from this research being used in Christina’s doctoral research.

Tickets for this event are £5 and they are available now by clicking here.

Thursday, May 12: An evening of poetry under our Best of the West Midlands banner, we’re delighted to welcome Liz Berry, Roz Goddard, and Casey Bailey (current Birmingham Poet Laureate) to the festival for an evening of rich and emotive poetry. This collective represents a wide span of writing perspectives, all of which speak to the roots of the West Midlands to some degree. Borrowing from their shared expertise in regional writing, Berry, Goddard and Bailey will deliver solo performances during this event to showcase their work and the evening will conclude with a question and answer session. During this, all three poets will welcome questions from audience members and they look forward to this open discussion dealing in poetics, publishing and pride for your roots, both in terms of writing and geographical setting.

Tickets for this event are £5 and they are available now by clicking here.

Friday, May 13: A panel featuring Rym Kechacha and Magda Knight as they discuss collaboration in a time of crisis. The cultural construct of a writer is someone holed up in their bohemian garret, toiling in solitude and silence to bring a work of genius to the world from a single, lauded soul. The reality of literature, publishing and reading is a cacophonous mess, a glorious riot of conversation, discussion, disagreement with writers and readers talking over each other across time and space. How to bridge the perception and reality? This panel will discuss the ways in which working with other writers and creators is not creatively invigorating but essential to the emerging culture of the twenty first century. The panel will consider: different kinds of collaboration within writing; internal and external barriers to collaboration; how we as artists can move away from the hero’s journey, to make our stories more representative of the collective. The panel will mix presentations, reflections, recommended reading, while also allowing for questions from the audience.

Tickets for this event are £5 and they are available now by clicking here.

Remember that alongside our festival events, we’re also orchestrating our annual awards ceremony and the first round of voting is open now. If you’d like to register your vote, you can do so by clicking here. Any questions about the programme or awards can be addressed to Charley via email at director@sabotagereviews.com.

]]>Winner of the Poetry Business’s International Book and Pamphlet Competition, In Your Absence is a striking pamphlet of poems which explore the aftermath of trauma, and the stages of grieving. Written in a fractured, almost hallucinatory style, these are many-voiced poems in which form and content marry to create an immersive experience. Unnerving visions and echoes bounce around in these poems, with the pamphlet’s title becoming a repeated refrain, alongside a series of images of everyday items which become shocking in the context of loss. In ‘Things I See on the Hard Shoulder’, the poet on their commute between home and hospital captures just how strangely the world is reframed in times of stress:

1. Shreds of sheeting grey as your skin whip-torn, forlorn, a vast ghost

flapping down the whole sad length of the M62

2. A never-ending diesel slipstream

3. A hard-hat, white, rolling like a skull

4. An oily rainbow a parallel universe a dark holding place a reverse

film on slippery celluloid we are the flickering ones streaming past each

other frame after frame.and three animals

I saw them love lying between us”

Here, the mundane is made uncanny, and the trope of a repeated number three is introduced, echoed later in poems which discuss the calming effect of counting and listing: “White Lies/ Feather/ Magic” and “Blood cells/ Hope/ White Light” as juxtaposed in the poem ‘House’ provide a stark and purposefully jarring contrast to the inkiness of the aforementioned poem.

Jill Penny comes from a theatrical background, and these poems demonstrate her adeptness with theatrical forms, often composed of fragmented dialogue in the vein of the late Sarah Kane. This post-dramatic approach is fitting, effortlessly evoking the confusing round of voices that punctuate hospital visits, and highlighting both language’s failures when faced with the task of processing death, and how grief rewires our brains. In ‘Dream I’, this phenomenon is explored through an immersion in white, the supposed colour of absence, interrupted by a host of voices wishing for the speaker’s attention:

Woman

The first white number according to the rules for colouring numbers

is 66. I find this significant in ways I can’t explain. Finding myself lost

in colour, especially the number blue, I wrap my arms in your aban-

doned sheets and fall asleep before it gets dark.Daughter

Dream poem.Woman

You kissed me in the blue lit public toilets

You were passionate as never so in life

You were eating peas out of the bird feeder

I said that was unhygienic.Man

Irrelevant.

In a book that offers no easy answers, the best the poet can suggest is a synthesising of a personal symbolism that serves as a testament to loss and love. In ‘Garden’, the penultimate poem in the first part of the pamphlet, the speaker tries to track the presence of the one they’ve lost, and can only leave us with a perpetually unanswered question:

Your presence lingers

on the lane

around the piano

behind the silent sewing machine

through each season

of this terrible year

in the white flowers

and objects I reflect on

in my garden.How can you not be here

in this wild white abstraction?

In Your Absence is a memorable excavation of the mysteries of death, populating its wild white abstraction with details that build a testament to a life lived, and the sadness of losing it.

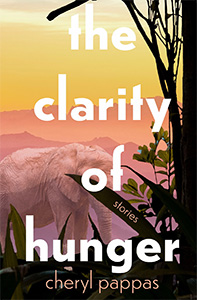

]]>Cheryl Pappas’ debut collection, The Clarity of Hunger (word west press), contains sixteen pieces of mostly experimental flash fiction. The stories take the form of hermit crab flash, prose poetry, hybrid, as well as more traditional realist and magical realist narratives, and often read like distorted fables. Whatever form each story takes, they all have something in common: a craving, a need.

Everything in this fearless short collection is symbolic, including the title; we all hunger for something. Robert Olen Butler promotes a compelling theory on this: he insists a story must have yearning. Kurt Vonnegut once put it another way: ‘Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.’ They’re both absolutely right. And Pappas is on to that. Magic — often dark — and allegory abound: the collection begins with a frozen old woman in a factory of women. She has been bent over, immobilised, for 24 hours, yet not one person has noticed. It’s only when the manager, a man, looks into the old woman’s eyes that he sees the problem. Inside each eye is a frozen lake. Immediately, he warms her in the fires of a basement furnace so that work in the factory above can continue. A metaphor for 21st century existence in the shape of a dark fable.

The two stand-out stories, for me, are ‘Tending the Elephant‘ and ‘Stranger‘. ‘Tending the Elephant‘ is in traditional form but has a magical realist narrative. A woman washes one side of a circus elephant, wondering if the man who washes the animal’s other side will arrive in time for them to work together.

The movement of the narrative, the passage of time is represented by a background Ferris wheel. It’s a magnificent embodiment of a natural clock.

The man arrives, staying “on the other side of 30,000 pounds of flesh.” In fact, the woman has never once seen him, though their work together tending the elephant is a shared physical experience. From either side, they talk while washing the elephant with lavender-scented soap. Alas, the immediate smell of her husband’s coffee calls her back to her realist duties, and her life. Reluctantly she leaves the unseen man to return to the obligations of marriage, the duties of motherhood.

The elephant is primarily a prop, an ocean, a land mass between two individuals who operate in different time zones. Their passion for the tending of the elephant is singular, but shared, yet they never get to see each other in the flesh. Everything is implied — it’s symbolic of the modern age, the internet, Twitter, Facebook, yet it’s delivered via magical realism.

‘Stranger‘ is beautifully written realist short fiction. Claire lives in Paris. Jacques lives in Orlando. She is married. He is not. They begin corresponding through short messages and photographs that zoom in on only specific parts of their bodies. Here, again, two people deeply connect from a distance, across time zones. The story magnifies the power of even the smallest exchanges — a reoccurring theme in Pappas’ work. Claire takes a flight to Paris to meet Jacques in person. In a restaurant they sit facing each other. “This was a mistake,” she said. Jacques sees things differently:

“But we are together. Do not take your hands away. It was you who invited me to sit here with you. I have come; I am here.”

It ends like a Paul Bowles tale and is flawlessly written — as poignant, as true, as any writer specialising in that genre.

Pappas also has the ability to meld genres and play with form, creating unusual, unsettling and sometimes superb hybrid pieces, with visual images and metred, lyrical prose.

‘Profile‘ reads like the melding of a prose poem and vignette: “curvy highways littered with plastic keychains”, and it is this clashing of forms — this hybridization — that Pappas does so well. If you’re a fan of Kathy Fish, and who isn’t?, then you’ll love this. Like Fish, Pappas is also absolutely fearless with form. The final story ‘Homework‘ is hermit crab flash in the shape of a multiple-choice questionnaire. It begins:

“Q: What is the end of your life?

A: Is it: a) a door closing slowly b) a meadow flush with golden buttercups, a rejoicing?”

The cold, objective delivery of the question, followed by the choice of striking imagery allows for the emotional response. And it does so indirectly, creating a greatly enhanced effect for the reader.

Clever. For students of flash this is a must.

Find out more about The Clarity of Hunger on the word west press website and visit Cheryl Pappas’ author website.

Reviewed by Peter Jordan — Peter is a short story writer from Belfast. He has won numerous bursaries and awards, including three Arts Council Grants. In 2018, he was nominated for Best Small Fictions and Best of Net. In 2017, he won the Bare Fiction prize, came second in the Fish and was shortlisted for the Bridport. He has also been shortlisted for the Bath flash and short story awards on three occasions as well as receiving a Pushcart nomination. Over 50 of his stories have appeared in literary magazines and journals. His award-winning short story collection, Calls to Distant Places, was published in 2019. A new short story is being produced by BBC radio. He is currently working on his second collection and a novel. You will find him on Twitter @pm_jordan.

]]>

Jill Widner’s chapbook, A Middle Eastern No (Southword Editions) is a collection of three short stories. Each story features a female protagonist who is learning to navigate the intricacies and complexities of her encounters.

Sylvie, the main character in ‘When Stars Fell Like Salt Before the Revolution’, is unable to recognize the limitations of her knowledge of the language and culture in Iran. She and her mother are about to leave Shiraz for Ahvaz—both located in Iran—before Sylvie must return home to the US for school. Before their departure to Ahvaz, they go to the local bazaar because her mother wants to buy Kilim. Sylvie is able to skilfully barter while she is at the bazaar.

However, language fails her at the end of her interaction with a goldsmith. After he has crafted a pair of earrings for her, the goldsmith, a man named Sahar Jazim, “writes something on a sheet of graph paper […] and Sylvie watches the Persian script appear”. He gives her the handwritten message and—in English—says, “‘What I have written is for you. Not for anyone else. Do you understand?’” Sylvie nods in reply. However, she doesn’t understand why he instructs her to keep his message private—a message she can’t read because it’s written in Farsi.

After Sylvie leaves the bazaar, she comes upon a young man in his late teens named Hussein. Hussein wants Sylvie to practice English with him. In the end, Hussein translates Sahar’s message for Sylvie. The message—a poem written by Hafez—reiterates Sahar’s request to keep his note private:

“I beg you, to no one else show/These words

I send in such a hidden way.”

Yet Sylvie’s curiosity drives her to decipher the poem which exposes the intimacy Sahar felt about their meeting—in spite of its brevity:

“Read these words in some safe place you find […]

You may speak any language to me / Love speaks

every language beneath the sun.”

For Alice, the main character in ‘Alice in Abqaiq’, opportunities for her to meet new people and make friends are prevented by language and cultural barriers. Both barriers bring to the forefront the loneliness she feels as an expat living in Saudi Arabia. At times, her loneliness manifests as frustration, exacerbated by language barriers that prevent her from understanding and communicating with others around her: one day while she is riding a company bus, she listens to a discussion among the bus driver, Sudip, and two women—all of whom are speaking in Hindi. At one point, it is obvious that the trio are speaking about Alice when “The word ‘American’” is “mixed into the wash of Hindi that [comes] from Sudip’s mouth.”

Alice’s emotional state is further complicated by the romantic feelings that she begins to develop for Sudip. As she continues to listen to the three speak in Hindi, Alice feels “herself growing uncomfortable again. She didn’t know how much Sudip might be telling them about her. About his relationship with her. Though the existence of a relationship between them had not been expressed.”

Their quasi-relationship never progresses because Alice always becomes guarded when she discovers that Sudip knows details about her and her life that she hasn’t disclosed to him or she hasn’t yet discovered about herself.

To the reader, Alice’s behaviour may seem odd though since, while riding the bus when Sudip is driving, Alice acknowledges that, “[s]he had thought that she knew him to some extent, and that he knew her.” Once they reach a certain level of intimacy, Alice confronts Sudip with a volley of questions. After she asks her questions, she realizes that it’s unrealistic to become romantically involved with him:

“‘Do you think you will marry me? Do you think my father will arrange for you to move

to the United States? Is that what you want?

‘I only want to be alone with you. I only want to smell your skin.’

‘You live in a room in a boarding house behind the Abqaiq Souk. You will never be for

me. I can never be for you.’”

As an American expat, Alice’s status in society is much higher than Sudip’s. Their short-lived romance is over before it has a chance to bloom making one wonder if this disastrous ending could have been avoided if, at the outset of their romantic connection, the two had an earnest conversation about their intentions and hopes for a possible union in spite of their social status in Saudi Arabia.

Yalda and Gillan’s friendship is also short-lived in the short story, ‘Yalda & Zhila’. A barrier of understanding is what eventually prevents Gillian from forming a closer relationship with Yalda. Initially, Gillian, whom Yalda’s mother continuously calls Zhila, is drawn to Yalda and the two girls are inseparable.

As time passes, and during the interactions that she shares with Yalda, Gillian discovers that Yalda can be impatient, insulting and dismissive: while the girls are spending time together one evening, Yalda informs Gillian that her mother has visited a friend as this “friend of hers is getting a divorce.” Gillian admits to Yalda that her parents too, “‘are getting divorced […] That’s why I’m spending the summer with my sister.’”

Instead of acknowledging what Gillian has said, Yalda changes the subject: “‘I’m not sure I believe her, though. I think she might be seeing someone.’”

In spite of Yalda’s less attractive qualities as a friend, Gillian continues to spend copious amounts of time with her. However, it is after Gillian sees Yalda’s behaviour towards their neighbour, Georgie, that Gillian decides she doesn’t want to be friends with Yalda. Georgie is in Yalda’s class at school and has Tourette Syndrome. Georgie’s episodes become normalized for Gillian. However, one day in late summer as the three girls are outside, Georgie has a bad episode. Afterwards, Yalda points at Georgie and says, “‘Only an imbecile pees on the ground in broad daylight’” before laughing and running away. Once Gillian bears witness to Yalda’s cruelty, she recognizes that, “[…] that was the was the day the way I felt about Yalda changed.” Gillian maintains the pretence that she is friends with Yalda. However, Gillian exacts revenge when she steals a family heirloom from Yalda.

Sylvie, Alice and Gillian, the protagonists in the short stories in Jill Widner’s chapbook, A Middle Eastern No, don’t always navigate their relationships honourably: Sylvie ignores Sahar’s only request, Alice confronts Sudip about their inequalities and Gillian steals a precious heirloom from Yalda.

Even though the language and cultural barriers — as well as barriers of understanding — are prevalent in the stories, they primarily serve to highlight the underlying problems that cause the three protagonists to abandon relationships they aren’t interested in pursuing.

And yet, in spite of these barriers, each short story provides a glimmer of hope as readers witness characters showing acts of kindness, extending a helping hand, and proving that their love can conquer all. Those moments of hope are ones that we should cling to as the world around us becomes even more divided. Widner poignantly captures the complexities of multicultural relationships and is a writer I hope to read more from in the future.

Find out more about A Middle Eastern No and Southword Editions chapbooks on the Munster Literature website.

Reviewed by Mikiko Fukuda — Mikiko obtained her MA in English Language and Literature from The University of Victoria in Canada. She has worked as a language and literature instructor at post-secondary institutions in Canada, Japan, Kuwait and Oman. She worked as the Editorial Manager at a publishing firm in Shanghai. She currently works as a freelancer for Oxford University Press.

An avid reader, Mikiko runs a book club and enjoys writing poetry and short stories.

Instagram: @mikifoo82 | Website: https://thetravellingeditor.blogspot.com/

]]>

The tradition of insect poetry has some illustrious examples; John Donne’s ‘The Flea’ written in 1633, being the most well-known. However, it is the poetry we intersect with as a child which resonates the longest. I received a copy of William Roscoe’s The Butterfly’s Ball and The Grasshopper’s Feast with nature notes by Richard Fritter and beautifully illustrated throughout by Alan Aldridge as a birthday gift from my godmother. It opened up another world beneath my feet. The Bee is not Afraid of Me is a cornucopia of forty-six poems and accompanying black and white illustrations, interesting facts with web addresses, project ideas for the enterprising parent or teacher, and an interview with a working entomologist which includes advice on how to approach a career in entomology. Inspiration takes many forms as all poets know. This book had its genesis from Fran Long’s former role as Project Insect Education Officer on the Oxford University Museum of Natural History’s Heritage Lottery Funded HOPE for the Future Project, and from the award winning poet Isabel Galleymore’s abiding passion for ecology and our human place within it. Poetry projects that arise from lofty intentions rarely realise themselves as well as this little gem of a book has. I absolutely loved it, and have no doubt it will open up the eyes and ears of children for generations to come.

The book opens with Myles Mcleod’s poem ‘Questions for an entomologist’, using questions in delightful wordplay that even brought a smile to this rather jaded ear. My favourite was

Do fleas flee like flies fly?

Do butterflies like butter?

Do horseflies fly horses?

Do bumblebees have bums?..

Celia Berrell’s ‘True bugs are suckers’ jaunty rhythm explains what I had never understood until now:

A true bug’s an insect,

but insects aren’t bugs

if they eat by chomp-chomp

instead of glug-glug

Anyone who has read poetry to children knows how often small hands creep into school satchels to nibble on something hidden there. Kate O’ Neil’s poem ‘Café Six’ is sure to be a hit with these munchers. Her café offers ‘fleas flambé’, ‘mosquito mousse’, ‘caterpillar curry’ as some of the more alliterative of dishes.

Of the poems written in the voice of an insect, Elli Woollard’s ‘Song of the Dung Beetle’ will garner not only a lot of chuckles if not guffaws at the implied colloqualism for excrement after “But I live in a pile, a big steaming pile, a HUGE steaming pile of….”

We learn there are three different types of dung beetle: rollers, tunnellers and dwellers, and that each is named for the way they use the poo they find. Susan Byrne’s ‘Our Planet’ follows this little fact box, and in it we learn how dependant we are on the small dung beetle. Poets have used natural imagery to discover important relations between the image and human experience. What is new in poetry are the poems inspired by deep ecology – the philosophy based on the belief that humans must radically change their relationship to nature. In a sense all of the poems in this collection reconnect the reader with the wild, bear witness to our insect brethren, and envision a place for the humble insect in children’s parlance. One poem in particular calls for a resistance against the way we have been conditioned to behave when met with what too many deem to be pests. Gabrielle Turner’s ‘A pest’s request’ could be read as a plea against intolerance of difference per se.

You call us creep crawlies

and you tell me I’m a pest,

but just like you, I’m living too

and I’m only trying my best.

No poetry collection would be complete without at least one acrostic poem. I do not know of any classroom that hasn’t an example pinned on the wall. They are often the first point of entry into poetry for children, and Nina Hoole’s ‘Dazzling Dragonflies’ is an excellent example of the genre. I was particularly impressed with: ‘Lace-veined wings fingerprint each species scientifically’. Jane Mackenzie’s ‘The Mayfly’ is a haiku which adheres strictly to the 5-7-5 syllabic count, but which relies on its title for seasonal reference. For those budding entomologists without recourse to computers or who do not have access to Wildlife Trusts, Ros Woolner’s poem ‘Pond Dipping’ charts a course. Its four lined verses move from iambic to tetrameter in a gently swaying motion, with an abcb rhyme scheme, lulling the reader into grabbing one of the below:

You don’t need much for pond dipping:

an ice cream tub or plastic tray,

and a net ot sieve to catch things in.

Got them? Good. Let’s go today!

I cannot think of any forgotten insect in these forty-six poems: butterflies (cabbage whites and fritillaries) moths, mayflies, termites, beetles, cockroaches, ants, honeybees, pond skaters, marmalade hoverflies, crickets, ladybirds, shield bugs all abound. Two poems have the Latin names of the genus as their chosen title: Pyrophorus Noctilus (Snapjack click beetle or Headlight beetle) and Episurphus Balteastus (or a case of mistaken identity), of which the latter has a lovely modernist twist in its take on the poetic couplet. I am still curious as to why it didn’t end with a full stop, but perhaps one of my younger co-readers will solve that particular mystery. The most arresting simile in the whole book comes from Robert Ensor’s ‘Aerial Gymnast in the Clothes of a Clown’ a paean to the honeybee. In line nine he says ‘yet you’re fragile as a child in the jaws of a hyena’. Elizabeth F. Hill’s ‘Name-calling’ is a fitting poem on which to end this review, reminding us that somewhere in our recent past, insects were thought important enough to name collectively; ‘bike of wasps’, ‘loveliness of ladybirds’. Long may they remain to flutter in kaleidoscopes of butterflies. And now to find a sieve to sit beside my local pond with. Published by Emma Press.

]]>