Claire Trévien’s Low Tide Lottery Launch @ The Phoenix Artists Club

It turns out Claire Trévien, Sabotage’s Poetry Editor, is a bit of a poet herself. I attended the launch of her first collection of poetry: Low Tide Lottery (published by Salt Publishing) at the charming Phoenix Artists Club.

I say she’s a bit of a poet, in fact she’s really very accomplished with writing published in Under the Radar, Ink Sweat & Tears, The Warwick Review, Nth Position and Fuselit and winning the Leaf Book’s 2010 Nano-Fiction competition.

The Phoenix Artists Club is a lovely little basement bar, with a kind of prohibition-meets-bohemian-Paris kind of feel. It seems the kind of bar in which you should be able to exchange poetry, prose or paintings for pints (but, to my knowledge, they only accept money).

Her themes

Seem to be the clash of sea and cities. Of old and new. In ‘The Swan’ (a wonderfully dirty and forlorn poem) a lonely German Shepherd, at once ‘a lonely dog’ and a ‘god transformed’, ignored by pedestrians on the streets that are ‘sweating trash’ trained only to look forwards and never take in the world around them. ‘Rusty Sea’ gives us an environment failing you, of something taken as a constant that turns on you, leaving the people to ‘wait for the tide to start again’. And ‘Low Tide Lottery’ seems to blend the ocean and the urban. It describes in spiky language the ‘rusty city’ exposed when a tidal pool shrinks and you can see the detritus sunk within. In her poems cities become wild and tempestuous and tides turn on you, becoming rusty and urban, while the mundane mixes with the mythical.

Her language

Trévien makes images and language do things they don’t normally do. In ‘Beg an Dorchem’ she comments that ‘the sky is crooked’ and hears ‘laughter catching fire’, showing us a landscape writing over itself. Her turns of phrase are lush and often playful, lines like ‘drunk on tables that spread their freckles’ resound with the anarchic revelry of bygone bohemians. Her language is contradictory and wild, but also often neatly beautiful, equal parts spiky and silk smooth.

Her performance

Is perfectly pitched. Her strong voice and grasp of tone makes poems like ‘The Shipwrecked House’ seem ghostly, all cracked and bereft. In ‘Belleville’, she revels in her language on the streets of Paris ‘minotaurs pulse from wall to wall’ and the ‘Rue de Belleville’s shirt is open’. When read, it sounds lively and joyous, her delivery setting off the poem perfectly. ‘Love From’ sounded like a well-thumbed poem, much like the postcards it described. Each place seemingly faded over time, let down by the correspondent who fails to identify the landmarks he’s sending. Her performance is precise, but brimming with meaning and emotion, bringing out her poems’ meanings.

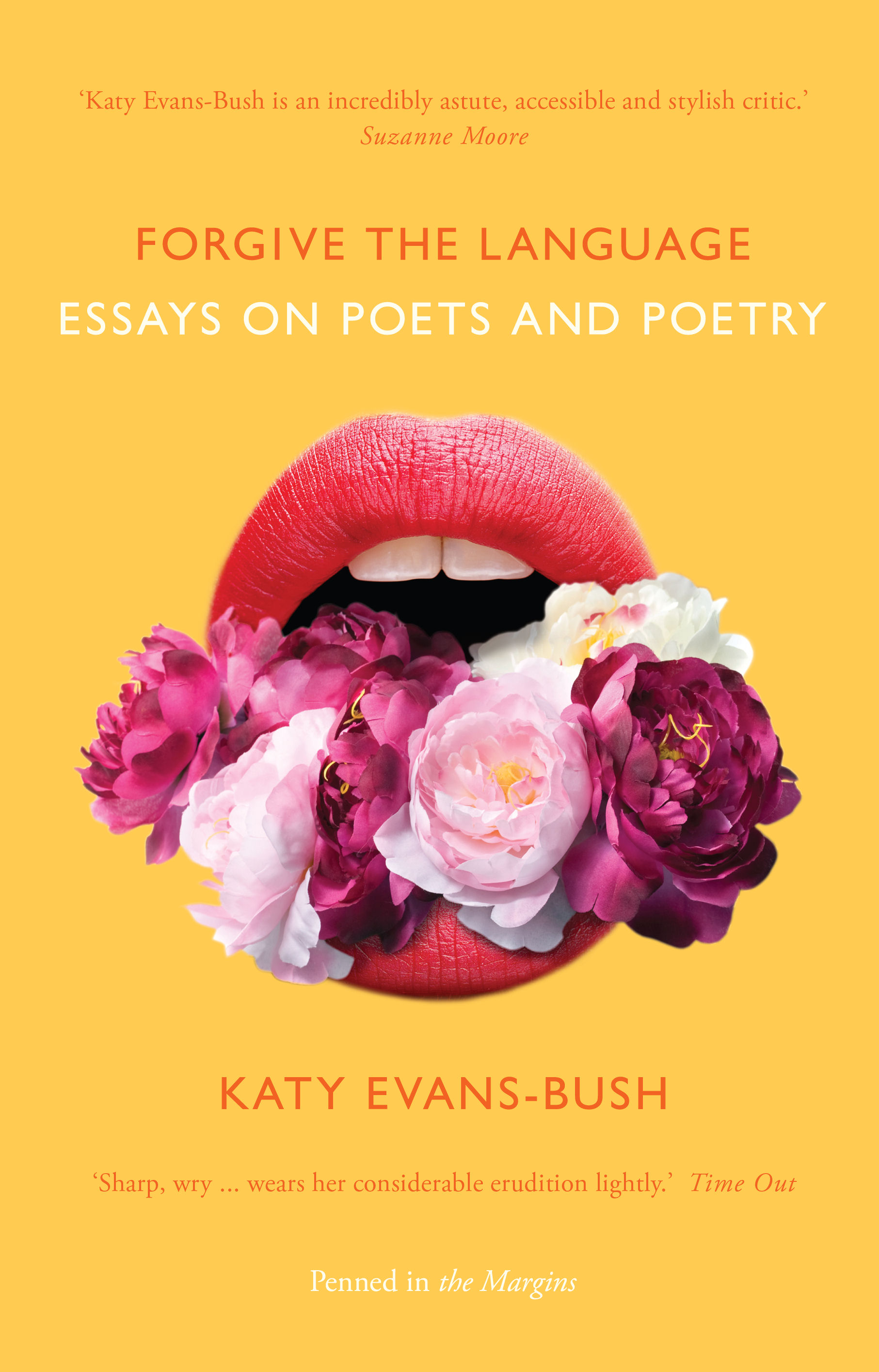

Also present to celebrate the launch and entertain the audience were poets Luke Kennard and Katy Evans Bush.

‘To read him is to be startled into remembering exactly how exciting and energetic language can be’ Andy Brown

Luke won the audience over quickly, his good natured jokes on writing and anecdotes about bookshops were amiable and showed a witty charisma that sparkled through his poems.

His humour

Is very apparent. The staccato matter-of-fact and intrusive absurdity of ‘Tragic Accident’ is both a caustic condemnation of journalism at its most base and uses repeated staccato jingoism for hilarious effect. ‘4 Neighbours’ idiosyncratic characters are united in their comic absurdity, from the meticulously described meticulous neighbour to the man who seems ‘embarrassed to be alive’; and the final character who writes about his neighbours in a column, commenting upon the narrator’s habit of staring is a worthy punchline.

His way with words

Is somewhat unique. You see it in the blend of the humdrum and haunting of the narrator exclaiming ‘that’s the last time I have sex with a ghost’ before the ghost takes the narrator to ‘A Pergola of Exceptional Beauty’ (also the title) ‘and a tower block collapsed in his chest’. To ‘Spade’ where he takes a symbolist view of a spade describing it as a ‘lever that punctures the world’ or as ‘opposite of a knife, it cannot be used accidentally’, its use and meaning becoming more abstract until the object is divorced from itself. His verbal dexterity is impressive; his phrases seem to bend language over itself in new and flexible ways.

His charisma

He seems dryly and quietly confident in performance. His knowing banter combines with an assured delivery that makes his poems easily accessible. Take ‘The 6 Times My Heart Broke’, a fragilely beautiful and increasingly surreal tale of heartbreak (sometimes literally). Or his ‘Mouthful of Stars’ in which he states ‘I’m converting to optimism’ describes a surreal kind of captivity that also keeps his audience captive.

Her Tone

She’s softly spoken, her delivery careful, caressing and quiet. The language in ‘Thibault’s Ribbon’, a super-cute poem on Gérard de Nerval’s pet lobster (‘un philosophe de la mer’) for example seems languid, but as words build and twist round each other it seems more coiled. ‘Rilke Puts Hammershøi out of his Element’ lightly sparkled, a supposed debate between two artists, she made the silence speak instead. The tone of her delivery coaxed the varied tones out of some very different poems.

Her Words that Enliven

Her poems seem to give life to the still, to build life and colour around little things. ‘Interior of the Great Hall at Lindegarden’, meanwhile, used phrases like building blocks, constructing a place for the audience to explore. ‘The Fabiola’ About an artist’s collection of portraits of St Fabiola, all copies as the original is lost, that form ‘a city in a room’ becoming a population or a congregation.

Her Words that Distance

The other side of her poetry, to me, was to create distance between objects and sometimes words themselves. ‘On a Note by Louise Bourgeois’ takes a phrase and tumbles it over, repeatedly rephrasing it, playing with ‘my memories are moth eaten’. With light nimble wordplay and ethereality to her words (‘my memories are the sails with which the moths fly), she rolls the phrase over and over until it’s out of sync with itself: thus reflecting the state of the subject. While ‘Portrait of Ida’ presents a portrait of a portrait being made, the subject and painter both alone, joined only through the brush on canvas.

It was a lovely evening, filled with some fantastic poets and poetry. I recommend you check them all out.