Alderburgh Poetry Festival 2-4 November 2012

-Reviewed by Judi Sutherland–

Aldeburgh – huddles of poetry lovers, but not very festive?

Arriving in this quiet Suffolk town on a Friday afternoon in November, you’d be forgiven for not realising there was a poetry festival going on at all. Where were the banners, the bunting and the buskers? I am more used to the Henley Festival, the Edinburgh Festival and Towersey Village Festival, where a range of sideshows, posters and children’s events create a joyful atmosphere of celebration. The liveliest thing in Aldeburgh was the smoked mackerel stall on the shingly beach. Maybe I’m missing something, but for a festival, it wasn’t very… festive.

To be fair, the Aldeburgh Festival is mostly not in Aldeburgh at all. The audience outgrew the cramped Jubilee Hall, and in this 24th year the events moved to nearby Snape Maltings, where larger venues are available. Aldeburgh veterans told me the whole event felt more ‘corporate’. For the first time, a free shuttle bus took the huddles of poetry lovers off to the huge and well-appointed theatres six miles away; a logistics solution that worked pretty well. Poets of all ages, shapes and sizes mingled in the foyer of the Britten Studio, where books were on sale, and the TLS and the Poetry Paper were interesting, learned giveaways.

Before we got there, we knew we weren’t going to hear everything we wanted to hear. I booked my tickets on line a month in advance but even so, many events were already sold out. Are the venues not yet big enough? Some other festivals offer festival tickets or day tickets, with which the punter can wander about and get in to any event where there is space. I found that the Aldeburgh Festival system denied me the spontaneity of the impulse-buy. Nonetheless, I settled in for the Friday night main reading with eager anticipation.

Friday – Nancy Gaffield, Leland Bardwell and Christopher Reid (Olivia McCannon strangely absent …)

It was strange from the start. The compere, Naomi Jaffa, first of all announced the winner of this year’s Fenton Aldeburgh prize for best first collection, who is Olivia McCannon. Jaffa told us she hadn’t met McCannon, but believed she was somewhere in the theatre; she wouldn’t invite her down to receive a large cheque because the prize money was nowadays paid by direct bank transfer, and then she misquoted the name of McCannon’s collection, which is, for the record, Exactly my Own Length. We were then treated to a reading by last year’s winner. As a PR exercise, this is a disaster. Imagine building up to the announcement of the winner of Strictly Come Dancing 2012, and then only showing us clips of Harry Judd’s 2011 performance? Here was a winner, sitting in the audience, with a prizewinning collection to read from, and she was silenced for a full twelve months, allowing all the fizz of interest to dissipate like flat coke.

Nancy Gaffield – last year’s winner – did read beautifully. Her spare and thoughtful collection Tokaido Road was based on a series of woodcuts she encountered when living in Japan. But, for a selection of ekphrastic poems, could we not have seen the inspirational artwork? I know there was a screen and overhead projector in the studio, because it was used on Saturday. Wouldn’t some visuals with Gaffield’s poetry have transformed our experience of the work?

Leland Bardwell, the 90-year-old Irish poet, was our second reader. The aptly-named Bardwell suffered a stroke three years ago, which has left her unable to read, but she recited some of the poems she has from memory. Her son Nicholas read her other poems, and they colluded memorably on the introductions. This woman has very definitely been A Character. In an aside to the audience, Nicholas Bardwell wryly commented ‘I’ve been around the block with this one’. After a fervent round of applause, Bardwell fairly danced back to her seat.

Christopher Reid, who is currently championing the long narrative poem, topped the bill on Friday night. In Nonsense, he thinly disguises himself as the ‘lately widowed and chronically befuddled’ Professor Winterthorn, off to an academic conference on the pursuit of futility. Reid tends to over explain the extracts in advance; the audience can pick up the narrative more easily than he expects. To my ear, Reid, who reads his poetry with a minimal emphasis on the rhyme and rhythm, sounds very like David Lodge or Tom Sharpe, whose bewildered academics inhabit the world of prose. I preferred Reid’s shorter pieces, which seemed more meaningful and less self-indulgent.

Saturday part 1 – John Stammers, David Wheatley and Julia Copus

The beauty of a festival like Aldeburgh is the chance to hear poets you know little about. Being a relative newcomer to poetry, I had heard of all three of the poets reading on Saturday morning, but knew very little about their work.

John Stammers was our first reader, whose low-key style was immediately likeable. I love the way some poets can take on popular culture as a basis for poetry. Stammers’ poem ‘The Other Dozier’ wonders about a forgotten Tamla Motown songwriter:

Turns out he had a tin ear

for everything except irony,

so his lyrics all emerged as modern verse

David Wheatley, followed, his poetry sailing close to the coast of zany. Several of his poems were shorter than their titles. There were many poems about birds and birdwatching, a popular subject for the introspective nature poet. My favourite, though, was a magnificently mad piece about the mediaeval habit of putting animals on trial. I’ve got to find that poem again.

After a comic first half, we regrouped for a change of atmosphere from Julia Copus, who apologised for not being so cheerful, reading from The World’s Two Smallest Humans. Most striking among these poems are Copus’ account of IVF treatment, in the sequence Ghost. It was not the most comfortable material to hear, but it faithfully charts an important modern human experience and it needs to be told. Lightening the atmosphere was the vibrant ‘L’Esprit de l’Escalier’ – a poem about the perfect putdown.

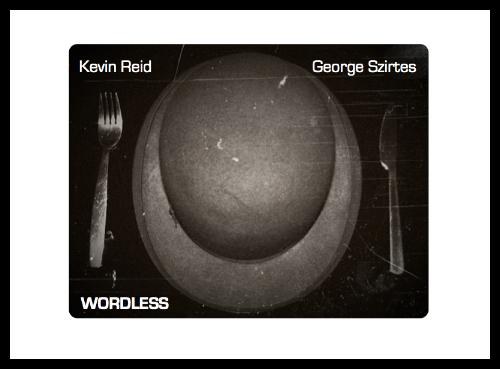

Saturday part 2 – The Song of Lunch (stealth-poetry?)

Time to grab something to eat – a difficult exercise, as Snape is somewhat under-catered at peak times – before The Song of Lunch, the BBC film of Christopher Reid’s poem. A middle aged publisher, played by Alan Rickman (Reid in another thin disguise), arranges to meet an old flame in a Soho Italian restaurant. First, Greg Wise, who wrote the screenplay, and Reid, discussed the making of the film in 2010. How depressing it was to hear that the BBC had to be cajoled and implored to film some poetry. ‘It isn’t a genre piece’, said Wise, ‘so the commissioning departments didn’t know what to do with it. We felt strongly that it shouldn’t have to be good for you, like broccoli or cod liver oil. The audience should not realise what it is watching’. So there. The only way to make an audience, or a broadcaster, like poetry is to smuggle it past them unawares. How utterly depressing. Despite the fact that the Aldeburgh festival is now too popular for Aldeburgh, it will be a while before poetry is the new rock and roll for our public service broadcaster.

Saturday part 3 – Anthony Thwaite, Ghassan Zaqtan and Jackie Kay

Anthony Thwaite, whom, we are told, is in his 83rd year, showed himself to be completely up to date with a poem called ‘Predictive Text’. I’d noticed that sometimes ‘good’ comes out as ‘home’, but Thwaite made a thoughtful poem from it. His poems were charming and witty. Thwaite told us, jovially: ‘I used to be studied in schools. Now they think I’m dead’.

The second poet, Ghassan Zaqtan, is Palestinian, and read in Arabic, with translations from Fady Joudah. Zaqtan speaks for his displaced nation, eloquently charting their suffering. ‘Pillow’ is an example:

Mother,

good evening,

I’ve come back

with a bullet in my heart

There is my pillow

I want to lie down

and rest.

Jackie Kay came after that harrowing reading, her warm personality illustrating the other end of the poetic range. There were of course some very moving moments in her reading; the eighty year friendship between two Scottish ladies charted in ‘My Fierie’, and the tender poem about her four year old son waking after an epileptic fit. But Kay reduced the audience to near hysteria with ‘Ma Broon’s Vagina Monologue’. As I grew up with the Sunday Post, I got the references straight away, but this poem is really about many women of a certain age, women of our mothers’ generation, and their ignorance of sex. At one point, Ma Broon cries: ‘But I haven’t got a vagina! I’m a cartoon!’ which made the Britten Studio shriek. It was so good to remember that poetry, although often serious, does not have to taste like cod liver oil.

Sunday – the collections of Sam Willetts, Fady Joudah and Andrea Porter

My last event of the weekend featured three first poets presenting their first collections. I was overjoyed to see that they were all over forty, therefore there is hope for those of us who come to poetry a little later in life.

Sam Willetts is ‘famous’ for the ten years he spent as a heroin addict. He quoted Beckett in the preface to his reading from New Light For the Old Dark: ‘It passed the time, but the time would have passed anyway’. His poems were indirectly about drugs, charting lost relationships and dead-end jobs, such as his time working with a rag and bone man. The poem about piles of salvaged furs in a freezing warehouse appealed to me -I’ve got a thing about work poems that allow us into unusual occupations, and this was vicarious labour par excellence.

Fady Joudah read his own work from The Earth in the Attic. Joudah is a Palestinian-American who works as an ER physician in Houston, Texas. He has also worked in Africa for Doctors Without Borders, and his poems describe operating theatres, refugee camps, and soldiers committing sex attacks. I listened, wondering about Western poets who attend workshops and take part in writing exercises in order to tempt a jaded muse. Joudah’s poetry is fuelled by an insistence that we should see what he has seen. For him, as for Zaqtan, poetry is an imperative.

If I was close to deciding that Western poets often write about trivia, Andrea Porter made me reassess that assumption. In A Season of Small Insanities, Porter addresses brutal aspects of modern life. In ‘Night Shift at the Petrol Station’ she records her daughter’s job, which included putting black modesty wrappers on porn magazines. ‘Haike With Her Dictionaries’ portrays a friend who worked as a simultaneous translator for the War Crimes Commission:

They brought six soldiers here. They dragged six boys here.

They executed them here. They shot them here.

Gesture left to speak.

They buried them here. They hid them here.

Gesture left to speak.

Pause. Rewind. Play Kosovo.

Her most personal series of poems was about a fatal car crash, caused by a drunk driver, in which Porter lost her partner and her unborn twins. If there is grief to be charted in Africa and Palestine, Willetts and Porter show that there is also grief in England.

I wasn’t able to attend a conversational exchange between Reid and Anthony Thwaite, but I am told they spent some time listing out their favourite bedtime reading. A canon of international poets from Eastern Europe to South America was mentioned, but not one single woman poet counted among their influences. I’m afraid that preoccupation with the usual suspects shows in their work.

Coming back next year?

The three of us who shared a seaside cottage for the weekend were all Aldeburgh newbies, and we all want to go back next year. It was exhilarating to spend so much time listening to very high quality poetry. There were lots of events I missed; the fifteen minute close readings, for example, that I’d like to make more of next year. I hope the festival takes over the enormous Snape Concert Hall with even more poetry. I was left reflecting on the atmosphere of the event. There was nothing much for children, there were none of the fun poetic sideshows that livened up last summer’s Poetry Parnassus. There were no collaborations with visual artists or musicians. The formats of the events I attended were unremittingly similar – three mainstream poets and a lectern. There was no slam, not enough workshops, and no bandstand for open mic busking. There is so much more the Poetry Trust could do with this, the largest poetry festival of the annual calendar, to showcase the whole world of spoken word.