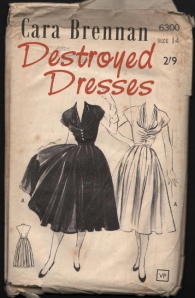

‘Couples’ by Michael Stewart and ‘Destroyed Dresses’ by Cara Brennan

-Reviewed by David Clarke–

Scarborough-based Valley Press is a relative newcomer, first established in 2008, but is quickly building a healthy roster of well-produced poetry titles with a distinct regional flavour. It has published a number of débuts, including Cara Brennan’s Destroyed Dresses (2012) and Michael Stewart’s Couples (2013). Both are pamphlet length, but – unlike many first pamphlets from new poets – these are notable for their cohesion and thematic focus. They are not just showcases of ‘best poems so far’, but rather carefully thought-through pieces of work which, for all of their brevity, are satisfying stand-alone collections.

Michael Stewart’s Couples is particularly notable for its use of the pamphlet form, presenting pairs of poems and prose poems which face each other on the odd and even pages of the book. Those on the odd pages are frequently justified to the right hand margin, so that they seem to lean into the poems on the even pages. The poems often talk to each other in a more or less direct way. For example, the openers ‘He’ and ‘She’ describe a bizarre suicide and the fate of the victim’s wife respectively. Similarly, ‘Him’ and ‘Her’ recount the sexual incompatibility of a couple from both perspectives. The trick here is that the reader understands more of the predicament than either of the subjects can, so that the pairing of the poems shows how it is lack of communication, not the problem of sex itself, which kills the relationship. The reader knows what needs to be said, but the characters cannot say it.

Overall, the collection’s take on love and coupledom is fairly bleak. Although it evokes passion and new love in some poems, the focus of the pamphlet as a whole is either on love gone wrong or, where the eponymous couples still survive, on the stagnation of long-term relationships. So, in ‘Cam and Shaft’, the man and wife have been ‘wearing away / like two moving parts / running together / until they stick.’ Similarly, in the prose poem ‘The Longest Married Couple’, a local journalist discovers that the centenarian husband and wife in question have survived by largely ignoring each other.

Stewart is also a novelist, and this is straight-talking poetry which shies away from simile and, for the most part, metaphor. Typically, the writing focuses on describing what people do and say, and refrains from any direct comment on those words and actions. In one of the most effective pairings of poems, ‘Clean’ and ‘The Spring Fires,’ we witness the reaction of a man and woman to the end of their marriages: she cleans her house until her fingers bleed, but he burns the entire contents of his on the back lawn. Stewart subtly comments here on the different ways in which men and women express hurt in our society, but does so skilfully by remaining on the surface of things. In ‘Clean,’ for example, we have the following description: ‘She scrubs the taps with Ajax, / she bleaches the bath with Domestos, / she scours the bowel with vinegar and wire.’ Clearly, it is the situation which is being foregrounded here and which is supposed to yield insight for the reader. A stress on musicality or a playful use of language are not strong features of this poetry, although occasionally Stewart will allow a rhyme to creep in as a parting shot at the end of a poem. Nevertheless, this no-nonsense, concrete style suits the subjects of the poems and Stewart’s unsentimental approach. It will be interesting to see how his future work brings this stance to bear on issues beyond the emotional and the domestic.

Cara Brennan’s collection is a more warm-hearted affair, in that the trajectory of the book roughly traces the move from the security of childhood through the dislocations of adolescence to the new security of a loving relationship. As the title suggests, clothing is a significant motif in the poems, both as a metaphor for identity and for that identity’s fragility. For example, the little girl of ‘Fifth Birthday,’ dressed in ‘pink and black check taffeta,’ is protected from a wintery outside world by her mother, whereas a slightly older version of this same child in ‘Bobble’ fears that the wind will pull off her hat as the family attempt to scatter her grandfather’s ashes. The fanciness and girlishness of this hat, ‘covered with scratchy fabric, / lace, a silk bow, pearls,’ becomes pathetic in the face of mortality and the hostile elements. In ‘Wool, Skin, Fur’, one of the most striking poems in the collection, a series of coats worn by the narrator at university charts her progress from insecurity and fear of exposure in her disorienting environment to a new confidence in a relationship with a partner whose coats now ‘hang with mine, against the door.’ Although not all of the poems focus on clothing, there are enough of these in the pamphlet as a whole to allow for a sense of progression and to tie the whole project together.

In contrast to Stewart, Brennan’s is a more conventionally lyrical voice. This is certainly not a criticism, but the poems do often focus on the perceptions of a female subject whose train of thought and feeling leads us to a moment of insight in which the details of the world around her take on a new significance. The already quoted ‘Bobble’ is a good example of this, ending with the fear that ‘A gust may take it away from me’; ‘it’ being not just the hat itself, but the loving family overshadowed at that moment by death. The language is far from showy, but Brennan is more willing than Stewart to develop extended metaphors, introduce evocative similes, and enjoy the sound of words. Just occasionally, these short lyrics fail to pack the punch of the best among them, as in the poems ‘Attic’ and ‘Sequin Dress’, where I found it hard in places to work out exactly what was going on. On the whole, however, Brennan is clearly a young writer who is capable of creating a world which is distinctly her own. She is unafraid of exploring her own vulnerabilities, but her work remains artful and controlled, so that her self-examination stays accessible to and engaging for the reader.

On the evidence of these two pamphlets, Valley Press has a good eye for emerging talent, and great care has clearly been taken over the design of the books. The cover price (£6 each) might seem steep, particularly in the case of Brennan’s slim pamphlet, though the RRP is no doubt a reflection of any bookseller’s potential cut. A better option for everyone is to buy directly from the Valley Press website where they are sold for only £5 each including P&P, or as an even cheaper e-book. Both pamphlets deserve readers, who will hopefully take advantage of the opportunity to buy direct.