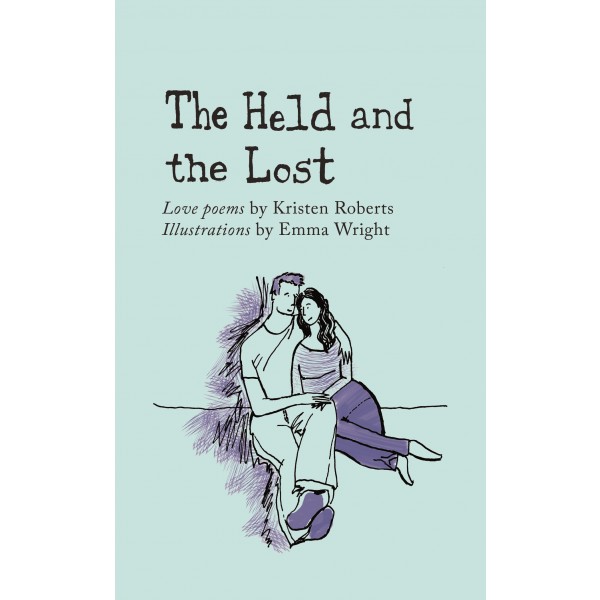

The Held and the Lost: love poems by Kristen Roberts; illustrations by Emma Wright

-Reviewed by Harry Giles–

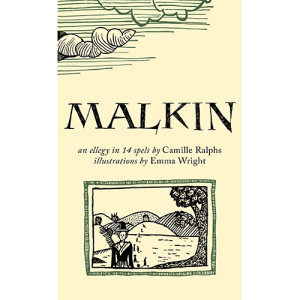

The Emma Press aims to publish “the kind of books you want to […] dip into on the train or while you’re waiting for the bus, as well as have on your ereader or phone like you would an mp3 of a favourite song”. I’m excited by this mission to make poetry accessible and desirable through suiting it to contemporary contexts. The Held and the Lost is the second publication from the press’s new Picks series, which presents new poets in beautifully-presented and affordable wee pamphlets. The design is charming and satisfying: slim, small and sturdy, so yes, absolutely right to slip into a pocket to bring poetry to the average commute

The poems are straightforward and direct, though not without depth. Stylistically, Roberts is unmannered and transparent; her language is mostly vernacular and without densely-patterned metre or rhyming. Lines tend to break at the end of a clause and almost every stanza finishes on a full stop, so this is poetry which feels easy to read, befriending the reader and holding their attention.

Though the language is lucid, it has its surprises. The chief pleasure in Roberts poetry for me is in surprising turns of phrase – those elusive poetic descriptions which are entirely new and entirely accurate. Frequently a lifeless object speaks or sings: in Night music a house is “exhaling a long sigh”; in Through a night window “the stars are humming”; in Going home “the gate squeals like a blues trumpeter”. Frequently the verbs and adverbs surprise with their unexpected suitability, as when in Through a night window “a spider sits thickly” and, naughtily, the season is described as “late spring uncoiling”.

Occasionally, though, the language drastically overstretches, as in Fracture when, tunelessly, “We tried to be emollient in our halving”, or in All kinds of sheep on the hills when shadows run, gather, spill, spook, follow and then “skim furrowed soil and bleed into flooding lakes”. The poetry is at its best when it is delicate and restrained; clusters of verbs and adjectives here sometimes overwhelm sense.

The poems tend to be descriptive in this way: they narrate brief nature scenes, with emotional events on their periphery, lending the scenes weight and meaning. A few of the poems are more intimate and interpersonal, as the cover’s loving couple might suggest, but the majority of the pamphlet describes scenes before or after the action has happened. The illustrations inside the pamphlet are thus sparse and evocative: they depict margins and edges of things through simply-sketched line-work, over which people cast faint shadows of movement.

I was most attracted to the poems with a depth of sorrow underneath the delicate description, where the tragic disjunct between careful words and rich raw feelings is most apparent:

The day we took our son to the sea

the swell was high and wine-bottle green,

the sky marked with curios of grace.

A dingy squealed the blues as it rocked up against the pier

and moaned whale-songs as it fell(To the Sea)

Here the power of Roberts’ description is apparent, allowing a carefully-shaped pathetic fallacy to carry her story. The facing illustration from Wright does its work beautifully too: beachgrass scratches to a third of the way up the page, with a few dotted human traces below and white space above. With poet and illustrator holding themselves back together, the sorrow of the poem sings through.

I was pleased by the pamphlet, though not delighted; I enjoyed myself, but wasn’t excited or overwhelmed. I tend to prefer poems that spark and cut, with shocks and jokes, to this more muted, imagistic work. Beyond that personal prejudice, though, I’d like commuter poetry to be a bit more adventurous. There’s no reason that a pamphlet designed for the pocket can’t challenge as well as please; there’s no reason that accessible work can’t take risks as well as entertain. But then, The Held and the Lost provides small beauties and quiet thoughts, and those are needed too.