Poetry Bingo by Maria Taylor

-Reviewed by Harry Giles–

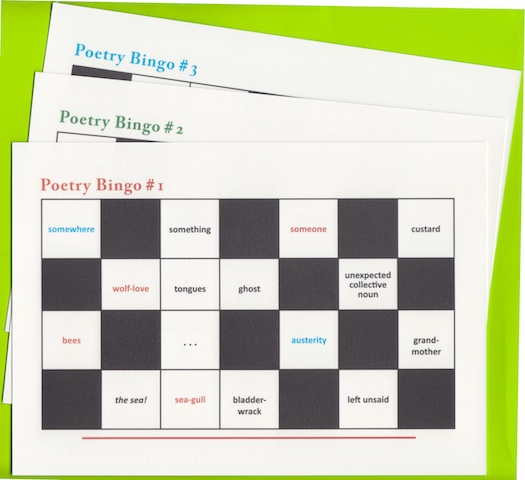

Poetry Bingo is, most obviously, a game. Each of Maria Taylor’s four cards features a traditional 7×4 grid with 16 carefully-selected poetic moves – from thousand-dollar words (“shards”, “breast”) to formatting conceits (“strike-through”, “…”), from structural ploys (“very long clever title”, “stirring epigraph”) to hard-to-find absurdities (“wolf-love”, “custard”). Taylor imagines a naughty audience at a poetry reading holding onto their cards, crossing off the moves and clichés as they appear, until somebody jumps up in the middle of a poem shouting “FULL HOUSE!”

Unlikely as that is to happen, the cards also function as an in-joke for poets. A bitter poet can wearily flick through the cards, seeing in the catch-all squares exactly the sort of poetry they despise. That said, though, I found the humour of the cards rather loving and gentle. As far as I can tell from the 64 selections, the cards are not prejudiced about form or movement – contemporary moves like “;-)” are alongside a more staid “elegies” and “rain”, “Freudian stuff” bangs up against “chickens”. And while finding a young-gun “austerity” next to a Laureatish “bees” makes me want to play spot-the-reference, the cards are mostly broad and innocuous enough to see any poet or poetry in them. Rather than a sullen jibe at a protective and mediocre old guard, or for that matter at an impatient and overreaching new generation, the cards through their abstraction are a fun-house mirror to hold up to any poetry.

I began to think about holding my own poems up to the bingo cards. What would it mean if I were able to hit a BINGO as I read through my own pamphlets? The cards are, in fact, mostly not skewering clichés – rather, they’re extracting a wide range of poetic moves from their formal contexts. In doing so, they make it easier to think about what each of these moves achieves, and so the cards can be imagined as a workshopping tool for poems. There’s nothing wrong per se in using a very long clever title, but it’s a decision based on a series of poetic traditions and expectations, not a piece of sui generis inspiration. Each move we make sites us within a politics and an aesthetics of poetry, and the arguments we make depend on the sequence of moves we play. This is not to say there aren’t still new moves to find – there are, and beating the bingo cards should come with a sense of triumph – but rather than there’s nothing wrong with making old moves in interesting ways. The bingo cards can be read as a kind of playbook.

They can also be read as a form of extreme visual poetry. In this interpretation, they have a lot in common with the types of suprematist and geometric concrete and sound poetry which seek to break language down into atomic components – except here, rather than breaking a word down into phonemes, the cards are breaking a poem down into its poetic strategies:

I remember somewhere dark very dark

ghostly mollusc love I think

gyrate waves salty fingers

memories O the sea silence

Here we find a concrete or perhaps found poem made up of common and uncommon components of poetry. There is a witty visual rhythm of consonances and juxtapositions which highlights the abilities and limitations of each component – we understand more what “mollusc” means and can do as it flows into “waves” and bashes against “gyrate”. The effect is humorous most of all – these poems are jokes – but all jokes are illuminating, because they reveal the assumptions and expectations underlying language, convention, and ideology.

If the cards have a flaw, it’s that they seem too terribly for poets – it’s hard to imagine a non-poet really getting the joke, and if there’s one thing poets don’t need its further encouragement to look inward. But in saying that, I start to think what would happen if an English class was handed a batch of cards before the Very Important Poet arrives to do their reading and bleak Q&A, and what would happen if, 20 minutes in, a well-known trouble-maker, who has been mysteriously attentive for this session, were to suddenly shout “FULL HOUSE!” That, I think, would be a much-needed sort of fresh engagement with poetry.