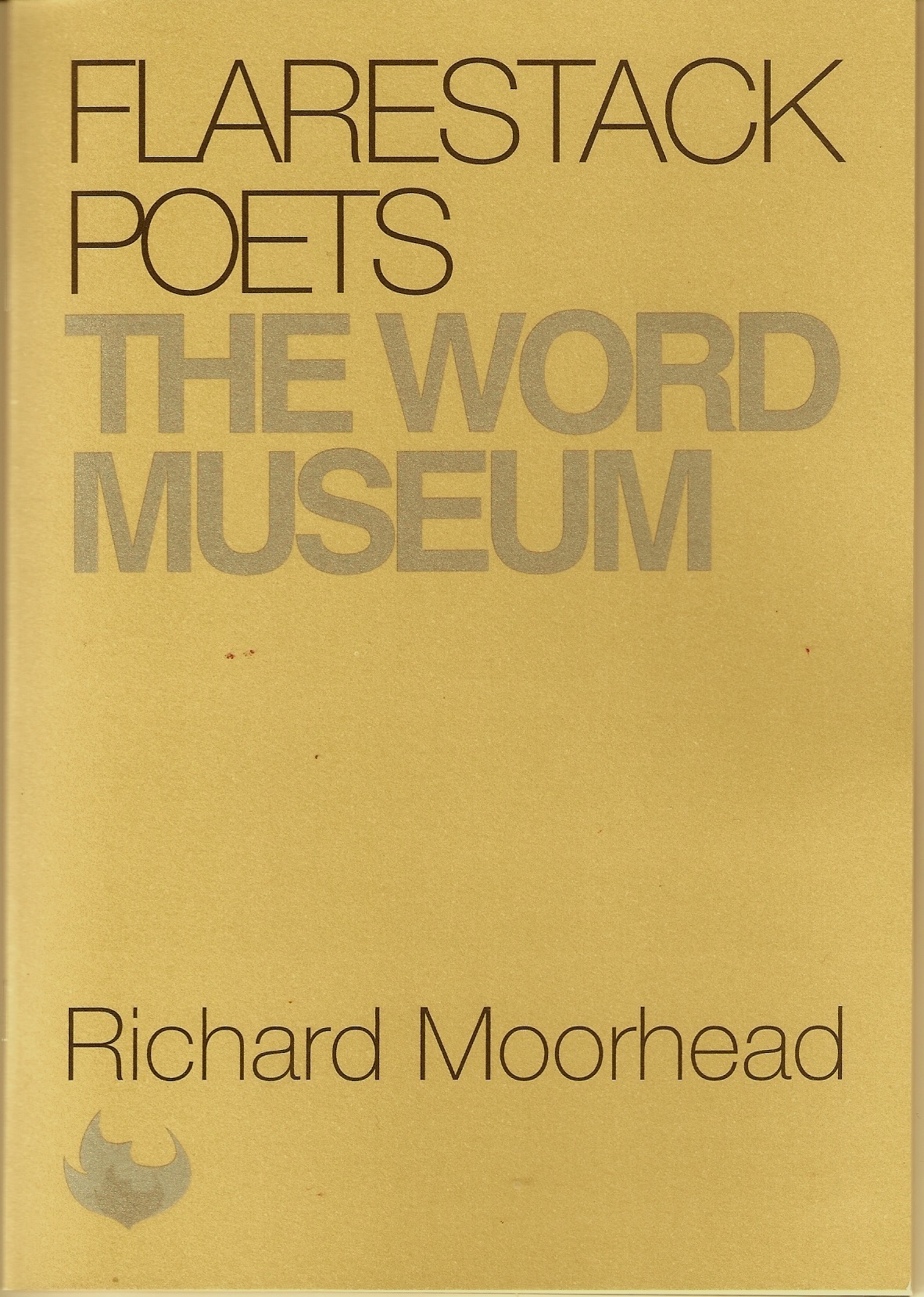

The Word Museum by Richard Moorhead

-Reviewed by Claire Trévien–

Richard Moorhead has a reputation for being a poet with a taste for poetic sequences particularly well-suited to the pamphlet format. His first pamphlet, The Reluctant Vegetarian, was a sequence of poems presented as if they were dictionary entries, defining and redefining fruit and vegetable. His new endeavour, The Word Museum, upgrades from comestibles to walk us through an exhibition of stories.

Framing the pamphlet is the language of curation, and it manifests itself even in the metadata, with the list of acknowledgements of previously published poems treating them as exhibits that have been ‘returned and restored. They belong here.’ The pamphlet itself is structured as a (self?)-guided tour, each poem headed by a note explaining its location within a house, such as:

Once you have paid for your ticket, you may examine the exhibits. Pass through the hallway, which broadens by the staircase. On the left is a small table with an assortment of post. Personal letters cannot be read. On the table they are fanned out. All addresses appear to be written in one hand, neat rather than elegant

This commentary pretends to be dispassionate, but it clearly isn’t. It imposes restrictions, ‘the letters cannot be read’, or dictates value judgement ‘neat rather than elegant’. This header appears to be a guide, as neutral and definitive as the voice it imitates, but what follows is a 5 part meditation on the instability of envelopes and the ambiguities they contain, particularly clearly expressed in the fifth part ‘A set of limitations’:

unsure what each page says of us,

or how the past spellsfutures we’ll know

soon enough.

As the reader is moved across the house, each carefully curated room triggers a story: the setting of a bathroom summons an ‘Anchor’ (‘A mile down everything tastes of glass:/glass and iron. The opposite of fire’), a side room with a kettle and biscuits brings up a ‘Kit-Kat’ (‘His tinfoil’s thin / and peels like Marjorie’s / sun drenched skin’). While poems such as ‘Player’ appear to be all surface (‘Here the trophies are of sex / each a solid guillemot of jet’), others fully exploit the relationship between header and poem to dive in and out of understanding. Case in point, a poem set in ‘the large bedroom’, on the bed of which is an envelope ‘with a handwritten label: “Instructions”’. The accompanying poem is titled ‘Lot’, immediately drawing parallels between the made bed and the Biblical character. The focus is on a husband in the first part:

Someone’s wife, no – husband,

dreaming of a soup

to dip his spouse in.

The years taste like her

or cream of artichoke

with a little lick of sin

This is a complex poem, meshing what appears to be an acrimonious divorce with the Biblical tale. In particular, Lot and his wife’s departure from Sodom, which famously ended with his wife disregarding instructions and turning around, to be transformed into a pillar of salt. Common to both are a disproportionate need to control women, which the sales language of the second part cements, meaning that this poem leaves a particularly bitter taste in the mouth.

Sometimes the setting makes the poem abundantly clear, as with ‘Noose’, which is prefaced with a description of a bent pipe on the ceiling, before a grotesque yet haunting study of the effects of strangulation:

How it thrilled the cartilage

strummed the pipesof bird bone in your neck,

the damped guitar strings of your voice box,

choked the tiny vole asleep there.No music, even at the end. Just the hollow

groan of pendulum. Its swing and creak.

Is the ‘I’ and the ‘you’ and the ‘her’ in these poems the same person? While the objects are allowed definition, people remain largely unnamed, unclaimed, like visitors drifting in and out of a museum. It’s tempting to try to read a narrative in these steered vignettes, but the hunt for a satisfying conclusion is ultimately frustrating: The Word Museum should be accepted for what it is (or isn’t): curiosities gathered by a collector of words.