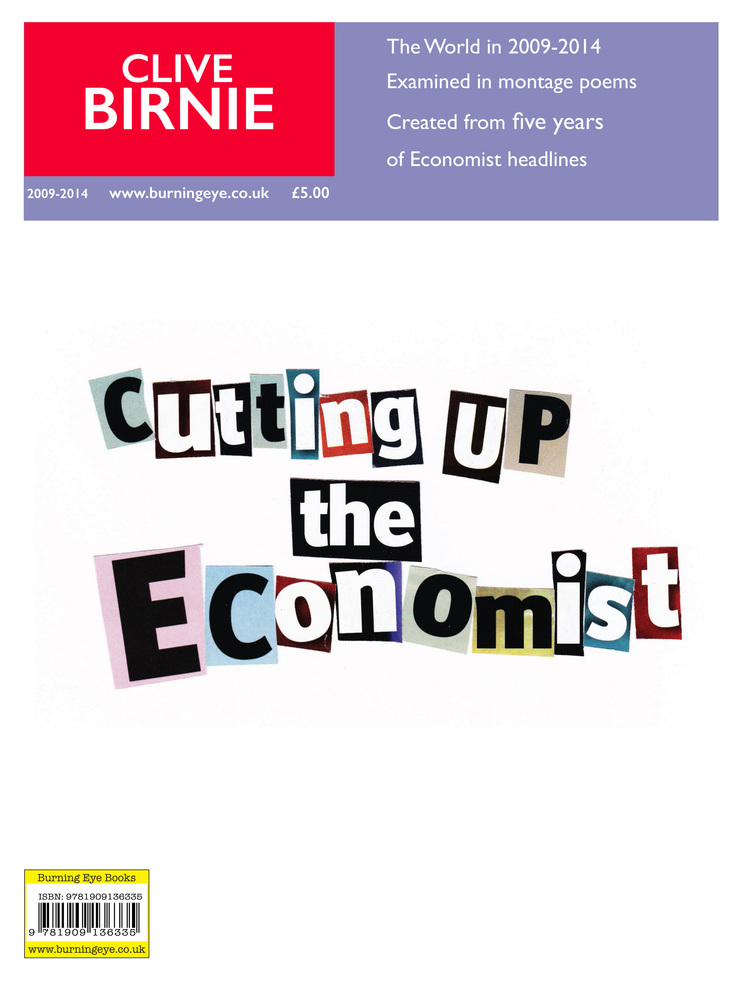

Cutting Up the Economist by Clive Birnie

-Reviewed by David Clarke–

Clive Birnie’s pamphlet Cutting up the Economist is the result of a five year project in which the author created cut-ups of headlines and contents pages from the eponymous news magazine in order to produce poems which reflect on the economic upheavals of the period 2009-2014. The poems are presented against a backdrop of digitally and manually manipulated images of pages from the magazine, none of which remain legible, and The Economist’s format is imitated in the physical presentation of the pamphlet: Birnie’s name appears in the characteristic red box at the top of the cover, where the name of the magazine would usually appear, and the size of the pages echoes the publication from which the text is culled.

This imitation immediately raises questions about the poems’ relationship to the magazine from which their words were taken, but Birnie is swift to clear up any potential assumption that he wants to take a critical look at the magazine and its world-view. In fact, the words ‘[t]his is NOT a critique of The Economist’ (emphasis in original) are the first that confront the reader in the pamphlet’s brief introductory text. I can see why this disclaimer might be necessary. After all, Birnie has been given permission to use the cut-out fragments of text from original copies of the magazine in his pamphlet. Nevertheless, this seems a curious premise for a work of this kind, a premise which is also evident in the sub-title on the pamphlet’s cover, promising that Birnie will offer ‘the world […] examined in montage poems created from five years of Economist headlines’. There seems to me to be a questionable assumption in Birine’s presentation of his work in this way. That assumption, as expressed in the sub-title cited above, is that, when we read a newspaper or magazine, we are able to examine ‘the world’, as if the language used by journalists was merely a transparent and objective medium through which information about that world could be communicated. I would argue, on the contrary, that any framing of reality in a particular kind of language is just that: a framing. Birnie may well be able to examine how The Economist uses language to present the world in a particular way, but he cannot claim to simply access that world objectively via the journalists’ language. This is no less pertinent when one considers The Economist’s own stated preference for economic liberalism, de-regulation, and so on (despite its claims to be beyond the left-right divide).

It is hard to know whether Birnie is serious about his disclaimer, and perhaps it does not matter greatly, but it might have been possible to dispose of this caveat in the introduction if he had chosen to use only the words from The Economist rather than copyrighted elements of its layout. This would arguably have constituted fair use in terms of subjecting published work to criticism, and the language is so dripping in cliché (more of this later), that it would in many cases be bizarre to claim that it was the intellectual property of the magazine. What is perhaps most interesting about the pamphlet, however, is that the poems themselves often escape Birnie’s stated aim of ‘NOT’ criticising The Economist.

To begin with, we see how journalists frame the causes of the financial crisis, which is a central concern of the pamphlet, in terms of blame. In one poem listed under the ‘Finance’ section (none of the poems have titles, but they are organised according to the magazine’s various rubrics), the term ‘BANKSTERS’ is repeated in capitals, down the page, interspersed with short comments on the banking sector. Although the first of these comments refers to the ‘rotten heart of finance’, by the end of the text the assignment of responsibility has shifted from a potentially more sweeping critique of the financial sector and its place in contemporary capitalism to the scapegoating of a few ‘[r]otten eggs and gadflies’: ‘Hold your nose’, the magazine instructs its readers. Implicit in such rhetorical manoeuvres is a desire to channel the ‘public anger’, which the journalists’ language acknowledges, into an appropriate disgust towards individuals presented as aberrations rather than products of the system. The poem captures this excellently, but that does not sit very neatly with Birnie’s proclaimed non-criticism of those journalists.

A number of the poems highlight a stereotypical use of language, demonstrating a similar disconnect between surface observation of the phenomena of the global crisis and any attempt at analysis of its causes. Given that Birnie has chosen to concentrate in the main on headlines, the province of sub-editors in search of eye-catching puns and pithy humour, this effect is particularly pronounced. One poem on the Euro crisis provides a typical example:

Time for Plan B

Bite the bullet

Hopes raised, punches pulled

Sovereign remedies

Unlucky for some

The next domino

Hard landing

Muddle, fuddle, toil and trouble

They’re bust. Admit it.

The labours of austerity

Northern lights, southern cross

A bank bail-out by

another name?

Every which way but solved

What is fascinating about this recourse to cliché and word-play is that, in the context of news reporting, it serves to obscure the underlying assumptions of a particular view of the crisis, which is solution-oriented in a very narrow sense and obsessed with a kind of perceived toughness (‘Bite the bullet’, ‘They’re bust. Admit it.’) whose human costs go un-interrogated (‘Unlucky for some’). This kind of thinking, where the best solution is the one that leads to the re-establishment of the status quo ante as quickly as possible, leaves no time for critical reflection on fundamental causes (not one of which is alluded to here) and encourages a sense of urgency and crisis (‘Time for Plan B’) conducive to unthinking haste. By estranging these pat phrases from their original context and placing them together in this montage, Birnie effectively brings into focus the weaknesses of the discourse and (whether he intends it or not) makes it possible for the reader to critique its ideological premises.

Another particular favourite of mine was a poem on German Chancellor Angela Merkel, which draws attention to the way in which female leaders are habitually referred to by their first names (a fate not shared, for example, by Vladimir Putin, who is the subject of the poem which follows this one). By repetitively listing such headlines (‘Angela at bay / Angela the dragon-slayer / Angela’s dilemma’) Birnie’s text rather comically suggests that we are dealing here not with the leader of Europe’s largest economic power, but rather with the plucky heroine of a series of children’s stories. I began to wonder: what will Angela get up to next? This poem speaks volumes about the gendered representation of female leaders, but can also be read as a commentary on the personalisation of politics, which presents the political as a series of soap-opera-ish conflicts between personalities, again obscuring underlying issues about the organisation of the economy and society.

I am aware in writing this that my interpretation of Birnie’s pamphlet may seem wilful, given the clarity with which the author defends the source of the language he is borrowing for his various montages. However, this defence is also undermined by the distortion of the pages which form the backdrop to the poems: Some appear melted, some appear scribbled over with black pen, others are torn or scrunched up, suggesting a sense of violence and disorder beneath the apparently confident and consistent discourse conveyed in the language of the poems themselves. Ultimately, whether one takes him at his word or not, Birnie’s poems perform the useful function of estranging the reader from the language which not just the journalists of this publication, but also the mainstream media more widely, have used to talk about the financial crisis. That does not get readers closer to understanding why that crisis occurred, but is potentially useful in terms of helping them to understand how the consensus over our response to it was manufactured.