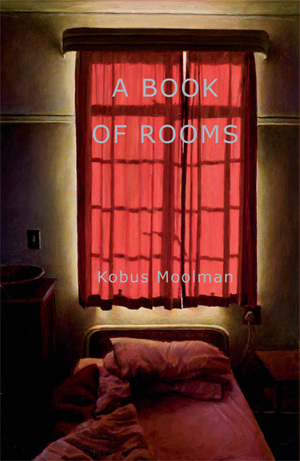

A Book of Rooms by Kobus Moolman

-Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey–

The multi-award-winning South African poet Kobus Moolman begins his seventh poetry collection with a quotation by Georges Perec:

Even if I have the help only of yellowing snapshots, a handful of eyewitness accounts and a few paltry documents to prop up my implausible memories, I have no alternative but to conjure up what for too many years I called the irrevocable: the things that were, the things that stopped, the things that were closed off – things that surely were and today are no longer, but things that also were so I may still be.

Moolman, like Perec, is a man haunted by his obsessions. A poet of deep sensitivity and integrity, he uses the extended conceit of rooms brilliantly, layering recurring images, the ‘yellowing snapshots’ of his youth, to summon up the ‘things that surely were’. But this is no ordinary series of reminiscences. These confessional poems are unlike any I’ve read before.

Divided into four sections, Who, What, Why and When, each poem is called after a room: The Room of Maybe, The Room of Green, The Room of Free-Falling, Forever, Not Downhill, The Room of Spillage, etc. The poems, written in the third person, are quite prose-like, most lines stretching right across the page. Although there are capital letters to start sentences, there are no full stops. The effect is of never-ending repetitions, an endlessness. And, although the images are bleak for the most part, and often sordid, they are compelling:

hands stained and sticky with hallucinations, his eyes swimming

straining, straining

like hungry dogs against the hot rope of their longing

‘I don’t believe in symbols,’ Pablo Neruda once said. ‘Simply material things.’ But when those material things accumulate and repeat, they become emotionally charged even when – or especially when – they are not pretty:

There is a smoky

room with a stuffed buffalo head on the wall outside the entrance

to the men’s toilet

stinking of urine and stomach gases, where dirty water lies on

the floor and crude cocks

are scrawled behind the cubicle door There are blacked-out

windows, a pool table

with heavy legs, and a television set in the corner without sound

playing soft porn

with Swedish subtitles (Ja Ja! Ja!)

Moolman creates setting like a cinematographer or playwright. (He has written several plays.) Many of these poems could be read as stage directions, bringing to mind Shakespeare’s ‘All the world’s a stage’.

But this is not the South Africa of the magnificent Drakensburg mountains, the Pacific Ocean, or national game parks. No wild flora and fauna, almost no beauty, even in the moments of love, or at least, sexual encounters. The world of this speaker is smeared, like a thin greasy film, with the cringing, sorrowful, material experiences of his upbringing, which exert a repelled fascination for the reader. This is a poet who does not shy away from the dark.

‘A Book of Rooms’ is dedicated to his recently deceased father, but his father is cast in a very poor light, without a single redeeming feature. Aside from rampant stinginess, mean-spiritedness and brutality, there are those moments observed by a young boy who imitates him after a spin-the-bottle game:

to force his tongue

inside You hurting me

just like he had seen his father do with Auntie Audrey (who was not really his auntie

just a good friend of his mother’s)

But if his father doesn’t come out of this collection at all well, neither does the speaker. One shameful event after another is described in forensic (if oblique) detail, suggesting a self-loathing, particularly in relation to the way he treated his younger brother. And yet, he retains our sympathy, especially in matters of love.

His first love is for his devoted mother. Then there is his first crush, who still has a hold on him. The vivid experience of his only night out with her exerts a preposterous power even decades later. When an older boy, a university student, steals her from him, we realize what the speaker is also up against:

And he (the boy with a hole in his heart, at the heart of

this story) feels everything

crumble and slide away beneath his small feet in their differently-

sized orthopaedic boots

and he leaves without saying anything to the girl

Although references to a congenital disability are oblique and fleeting, they are also subliminally pervasive.

Which is not to say the story is harrowing throughout. Some poems describe seduction. Even marriage:

There is

a tall blue sky without any railings He remembers He remembers

the woman saying

Marry me With this body I thee worship

While there isn’t enough lyricism for my taste (that ‘tall blue sky without any railings’ is all the more striking for being a rare example), there is a rhythmic power to the repetitions. And there is a dark humour too, and a certain recognition:

There is the same

old pine desk with four drawers filled with unopened NBS bank

statements and old

school exercise books he had bought because the girl with the

red hair, who had a

boyfriend waiting for her at home, had told him that all real

writers keep notebooks

for their profound thoughts and ideas But since he had never

had any profound thoughts

and ideas (or the discipline to be still and listen for them) the

books are still sealed

in their brown paper wrapping

Moolman is one of the rawest and most honest poets I have ever come across – not even Sharon Olds comes close. Building on the insights of his last collection, Left Over, where Kobus Moolman found a dramatic way to write about his physicality, this haunting collection brings home, forcibly, the sense that, as well as the room of our body, we live in the rooms of our memories, and it is from these rooms that we experience our life.