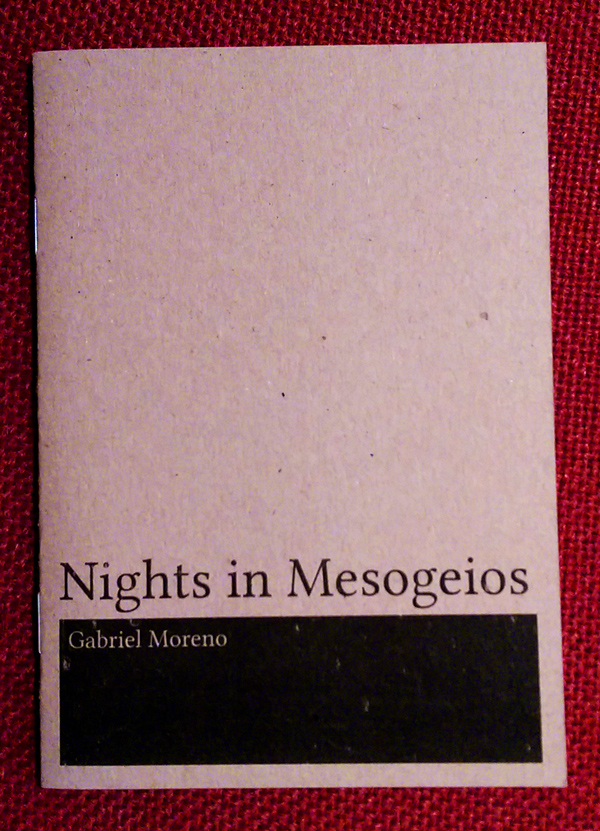

Nights in Mesogeios by Gabriel Moreno

-Reviewed by Owen Vince–

Properly, the subject of Gabriel Moreno’s Nights in Mesogeois is song and the voice that sings. It is a lyric poetry that grounds itself like an electric current in a poetry of celebration as well as mourning. Each of this pamphlet’s six poems offers a heady, bristling language to deliver its meditations on love, the death of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, songs of Gibraltar, cigarettes and playing hooky in a park. But, across its short pages, it also tests the possibilities of archaic forms and diction in contemporary poetry.

To begin with, in “A few things mattered”, Moreno sets up a dramatic romance that counteracts the poem’s politely humble title, in a way both humdrum and elatedly romantic –

The night was propitious,

all the bars in the world were aligned.

There were more words in your flesh

than in all the scrolls of the Red Sea

His lover, the poem’s subject, is given to us in both delicate and dramatic words. It is a drunken imagination of love, of its youthful splendour – “we buckled ourselves to romance / with the straps of our drinking”. But for its grandiose romance, the poet also winks at himself. The poem’s smile raising line of “My limbs wailed / when you spoke. I quit puberty” lambasts the brilliance of aureoled romantic words and sonnets. “It had to end”, he says, “it always does”.

The meat of the collection, however, are its more imagistic explorations into history and literature. “On the death of Elizabeth Barrett Browning” is a beautiful, though perhaps ill-fitting, poem. It is the poem most unlike the other five poems in the pamphlet. But it is also very clever in its lyricism, its line breaks perfectly, adroitly handled, and is worth quoting at length –

I want a slow fall

from any coloured terrace.

Past the violet hour,

escorted by a breeze

of aureate flowers.

Naked, my organs lit

like chestnut fire

This is what Moreno does so well – to hand the reader concrete things, beautiful and almost glittering in their rightness (“my organs lit / like chestnut fire”!), but also to lift them away, to transcend them. Is this Browning the poet, an imagined suicide note, a message from beyond death? Its coordinates hint at something beyond, while its language – however effervescent – bubbles away in the present moment, as with “the poppy / dispossessed of its petals”. In these lines, Moreno is being the poet we all want to be. He has that sure handling of “literary” and historical subject matter which Burnside also has, a way of talking about it without us needing to know much about Browning or her poetry – if we don’t -, without having to read the verses alongside some literary biography.

This is most appropriately reflected in the pamphlet’s wonderful “Ballad of the death of Federico Garcia Lorca”. Appropriately, for its form, the poet celebrates the man, the poet Lorca, dancingly. Its lines use a loose meter of iambs and trimeter to give a pleasingly musical effect to the reading – an effect that also gives it a powerful imperative ability to make declarations and to ask questions –

Where are the gypsies, Lorca?

mocks the captain of the men,

are they coming to the fiesta?

Are they hiding in their caves?

Appropriately, the poem closes with a ferocious and romantic image that suits so well Moreno’s talent, and does not – quite – suffer the problem of sounding hollowly archaic – “rage for the son of Granada”. That the final line grounds itself in this trochee allows the poem to close like a fuse burning out. Moreno in fact returns to Lorca in the accompanying poem, “Upon the murals of Lorca’s sleepless city”, which again casts around in a language which reaches toward the modern as well as the archaic – with “plucking the strings of your lute / as they fecundate themselves” against “baseball capped pistoleros / spin around in monster trucks”. Perhaps at times these archaisms ring faintly inauthentic, to my ear, but Moreno generally does a masterful job of recovering them through modern contexts and imaginations – the lute and the monster truck, underground fumes and “the coterie of your words”. Here, Moreno seems to be asking of poetry whether it can sustain its epic form, its drama and romanticism, in a world of modern selves and sensibilities (it can, though with some fragility).

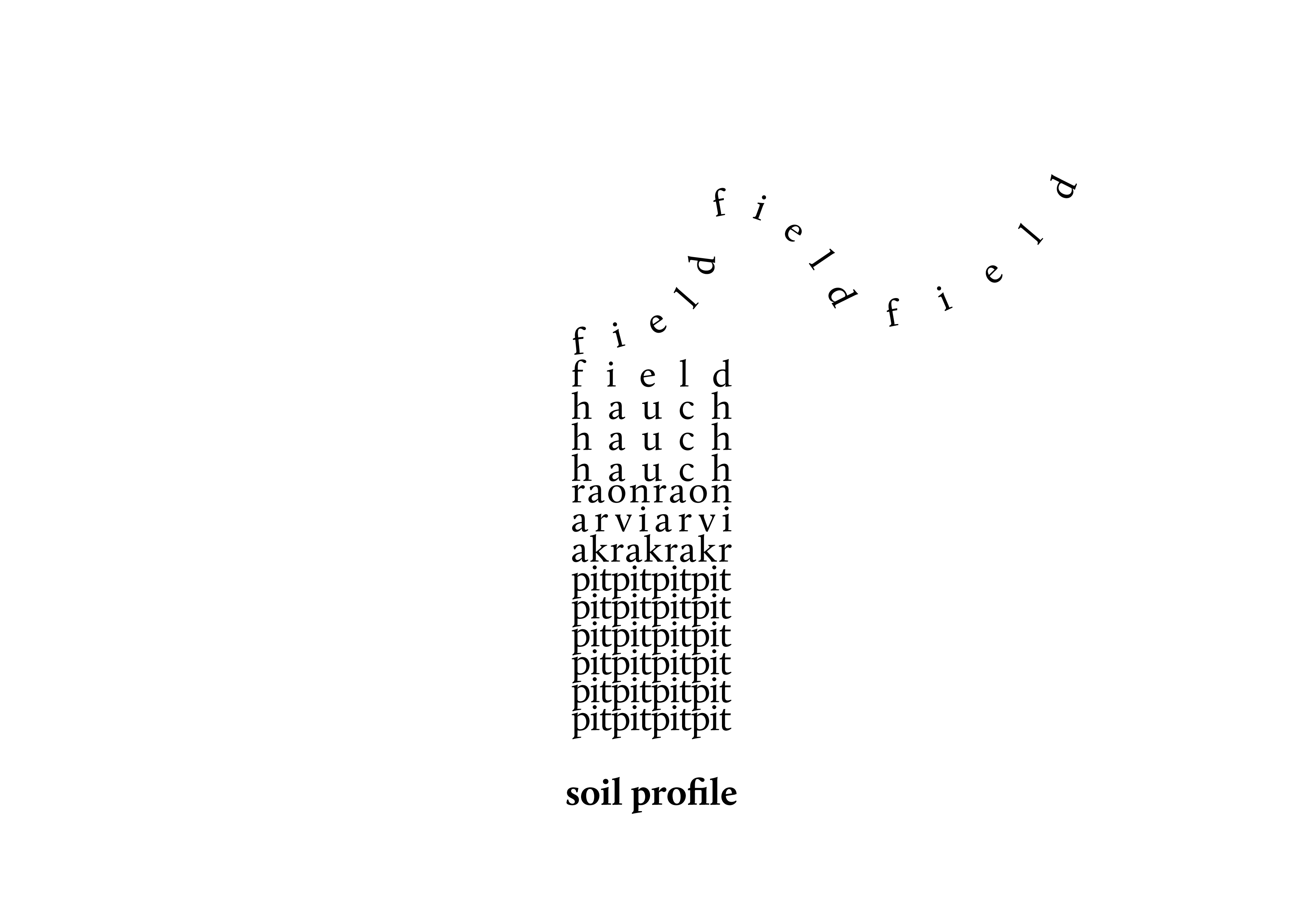

On a more physical level, it’s also hard not to be pleased with the minutiae and delicacy of these little, brittle Annex pamphlets – it has a rough paper cover and a minimalist arrangement of title and author. Its covers are like box lids and its pages pleasing to flip among, almost like bible paper (albeit, a little thicker than bible paper). It has the same oily quickness to it, the pleasure of a well-made thing.

But regardless of the object of the pamphlet, Moreno is so successful – in his verse – because he singingly turns his poetry toward both its histories and its present. It celebrates poetry as a medium for lyric story-telling, for conversations of love and the importance, thenecessity, of words (and, as such, of poetry – as a kind of song or singing). Such necessity is emphasised in the pamphlet’s very final line, of “Remember to write me, I say, / don’t forget to keep me alive”. It would not be so strained to say that this is not Moreno speaking, or one of the poet’s subjects, but poetry itself.