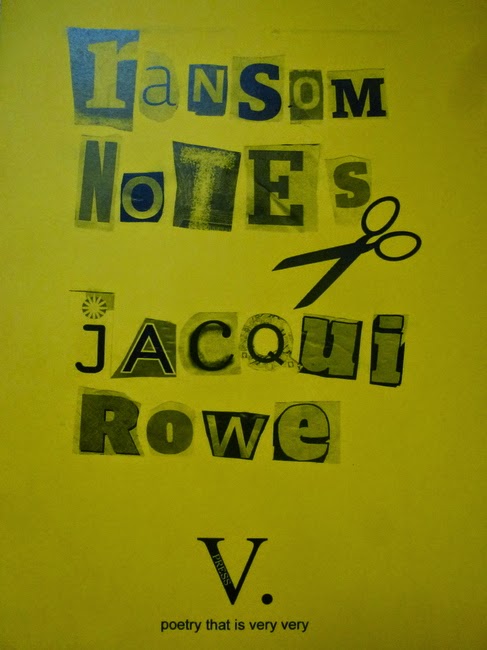

Ransom Notes by Jacqui Rowe

– Reviewed by Alice Tarbuck –

Ransom Notes is Jacqui Rowe’s fourth pamphlet, and focuses on the fraught relationship between constructing text and constructing meaning. The collection operates as a series of ‘ransom notes’, as the title suggests, in the long tradition of found poetry. Traceless fragments are collated and shaped by Rowe to form a series of curious poems that create a scale, from the almost syntactically straightforward to oblique, fractured works that gesture toward linguistic chaos. Of the former, perhaps the most interesting is ‘Gullet’. Occurring in the middle of the collection, it is the work that most clearly attempts a narrative arc, albeit a fantastically surreal one:

bodies were stashed

over the sink in a sack

of ceiling its belly

The reader encounters a hoard of bodies, bundled into a space above a kitchen. Sibilance softens the shock of this discovery, the plosive ‘b’ of the bodies modulated by the whispering ‘s’. Throughout this collection, Rowe explores the way in which aural correspondence between words can operate as an alternative syntax, inviting readings of tone and pairings of words beyond the constraints of grammar.

She is also invested in the grammar of spaces – both the space of the text and the spaces in her poems. Here, the house is figured like a body, with ‘its belly’. This transference of epithets through lack of clarifying punctuation is one of Rowe’s strengths in this collection.

House as body is developed in the next stanza through the image of ‘blinds / lined with yellow smelling / skin’. The blinds here might be decomposing eyelids, or simply have the qualities of skin. This unsavoury ambiguity lingers through the poem, culminating in the final stanza, where the dead, perhaps, fall from their hiding place and kill the inhabitants of the house:

in corridors one day wrinkled

jam on a plate the dead

would flatten them

Rowe does something interesting here, the visual image of ‘wrinkled/jam on a plate’ suggestive of oozing blood, before the dead flatten their subject. This foreshadowing reinforces the house’s eerie sentience, and walks, once again, a fine line between the literal and the metaphorical. This appears to be both a grim tale and a poem about the force of memory, the jam a Proustian catalyst.

Rowe’s collection also holds some works that are considerably less polished: instead, she has allowed snippets of found text to maintain their unexpected edges. These poems offer the reader a different type of reading experience. Rather than working toward discovering meaning and internal cohesion – a strong temptation in works such as ‘Gullet’ – the reader is directed toward a more experiential type of reading, wherein aural and textual components are released from syntactic pressure and allowed to operate independently.

One such poem is ‘Cottage’, which makes frequent use of non-grammatical text arrangements to demonstrate and challenge traditional allegorical archetypes commonly found in fairy tales:

one of the gifts is misremembered

as intelligence saved her from hovering

women beasts undergrowth if not

The ‘gifts’ might chime with the gifts given to princesses at the beginning of fairy tales, usually addled by a curse from the uninvited ‘Bad Fairy’. Here, ‘intelligence’ may be the gift – certainly it takes on a salvific quality – but we are not on firm ground. ‘Hovering’ takes us up, out of the narrative we are entering, and instead places us amongst ‘women beasts undergrowth’. These three words might triangulate around ideas of female genitalia and its oppression, but they also may well ‘not’, as the poem suggests.

This investment in keeping multiple possibilities for meaning open can also be seen in one of the last poems in the collection, ‘Chrysanthemums’. The beginning, ‘cars fold in the window a hand / clap between them’, offers us a glimpse into a specific perceptive: are the cars seeming to disappear due to the orientation of the window? Or are they tiny cars, paper cars, something else entirely?

Rowe enjoys playing with meaning, but is also aware of the potency of the non-meaningful in found poetry. Whilst the collection can feel, on first reading, as if it has no internal coherence, themes and characters, faintly glimpsed, emerge on further exploration. Additionally, as a poet interested in new ways of reading language, the tantalizing lack of punctuation makes this poetry feel flexible, as if what is found there might alter according to the reader’s whim. A fascinating pamphlet.