Boscombe Revolution #3

– Reviewed by Jennifer Edgecombe –

Issue 3 of Boscombe Revolution is a collection of 21 poems and prose, by 17 authors, on the following themes:

*work which interprets ‘revolution’ from a women’s / feminist perspective

*work from Black women and other Women of Colour

*work from poets and writers of all genders, sexual orientations and dis / abilities

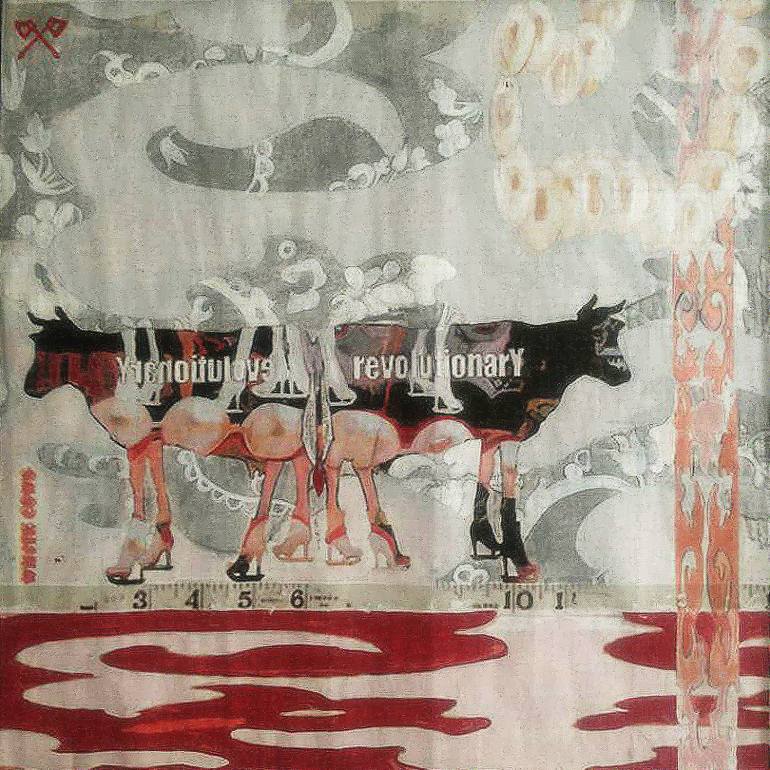

The cover art is by Birgitte Moos, from ‘White Cows’, featuring two cows back-to-back ice-skating on a ruler. Moos explains that it is an anti-commercial image based on the fact that the first fashion show in Copenhagen was located in a former slaughterhouse. Moos goes on to say that she was labelled as a ‘White Cow’ by her studio landlord, because the slang represented the culture of radical female obsession with beauty at that time. The mirrored cows, a tribute to Lacan’s ‘Theory of Mirrors’, show how women copy the model of classical beauty imposed upon them by financial corporations. This leads to women narcissistically ‘mirroring ourselves in other women’s eye-catching appearance.’ The three poems I review below show the extent that each gender measures itself against this model for self-recognition and self-approval.

The character in the first poem, ‘Orca Play’ by Lucy Humphreys, stands in front of a mirror preened and presented to amplify her assets, ‘De-haired, moisturised, pink thong, push-up bra’. She anxiously repeats, ‘I don’t want to’. The poem cuts to a vicious image of a heavy and lethal whale dragging down a victim by pushing down on it with its weight, before tossing it into the air and eating it:

The killer whale body-surfs his weight onto his prey,

drags the toy out to deeper water,

flings it, spinning loose-bodied, into the air –

guzzles down, grunting.

My first notion is that she feels prey to the whale and is drowning underneath her own heaviness, underneath the fat she sees reflected or imagines around her body. The sexual connotations of her dress suggests that the whale could also be her own self-image as she descends on a lover. Her fat has become disproportionate – so large that she can ‘body surf’ and she guzzles instead of kisses. However, it could also be argued that the whale is instead a man having sex with her, and she is the delicately spruced ‘toy’ being tossed around.

The final stanza suggests that both images are correct:

She doesn’t cry, wraps herself in her blanket’s embrace,

dreams of ballet dancing and violations on the staircase.

The last line, ‘ballet dancing and violations’ crudely contrasts her sexual frustration – if only she felt better about her weight and self-appearance, if only she was ‘weightless’ and light enough to delicately ballet dance – with her feeling after the apparently sexual act. She has no lover but only a blanket to embrace her, and her dreams of ballet dancing are mixed with the horror of violation.

This character has absorbed society’s model of a ‘perfect body’ and is reflecting it against her body in the mirror. Even with ‘improvements’ (a ‘pink thong’ to suggest provocative beauty and a push-up bra to enhance features to a larger and more sexually-gratifying proportion), she feels ‘prey’ to her own weight and image. In the second reading, her image has become manicured to that of a ‘toy’ that is worthless.

This simple 10 line poem expresses the concern within both female and male society to look a particular way and to regard natural parts of the body as insufficient or disgusting. We don’t know the end part of the sentence ‘I don’t want to’, and this omission expresses that something needs to be vocalised. By hiding it, and instead producing the image of the whale, the reader is subjected to her anxiety and stress.

Emma Lee‘s poem is just as short and just as powerful. It begins by following on from her title, ‘Smile, Baby’:

Is not a friendly hello,

is not even a greeting.

Brings to mind the song, Don’t call me…

or ‘That’s not my name…’

Lee questions a person’s right to command somebody to do something that will make them appear nicer to that person. This action is belittling, not using a name, but ‘Baby’, a word that is stereotypically derogative. She is shocked by this person assuming that her face should look how they want it to look, and that she should be smiling for their gratification:

It jerks me from where I am,

jerks me from who I am,

jerks me into noticing not you

but your belief public space is your space.What if I said, Wash your hair,

go on a diet, work out,

smile for me?

Would you?

The use of the word ‘jerk’ three times in the middle stanza not only implies her ferocious feeling towards the ‘jerk’ who has insulted her but also implies that the stranger has mentally shaken her from her original path. It also alludes to physical abuse and anger that suppresses a woman into a certain model. Lee’s frustrated response indicates various factors that she feels she has to conform to in order to fit in with socially-accepted appearance; dieting, working out, washing and styling her hair.

This zine also features a poem by Markie Burnhope called ‘aboy’. It begins with a schoolchild, ‘a boy’, hanging his coat on a hook with a daffodil on it. The poem winds down the page in one or two-line stanzas in the shape of a curve or a hook – a backwards ‘S’ shape:

my nursery school hook

nailed to a ceramic tile

of a daffodil

me to my mother

helping me with my coat

when I grow up

to be a girland the long space left

in place

of a response

As well as the shape of the hook, the curving form reminds me of the feminine ‘S’ shape, the natural curve of the body, also the shape female models are asked to bend their bodies into in order to create the hourglass deemed most attractive for posing.

Just as Lee was caught or ‘jerked’ into a place where she didn’t expect to be, Burnhope’s character is caught out by this hook. ‘The long space left in place of a response’ indicates both the dismissal of gender preferences and the reluctance to talk about it. We don’t know how long the space was left; it could have been until the character was a grown up, still dealing with this issue.

We shouldn’t have to measure our weight, appearance, sexual orientation and gender preferences against any model, but are continually falling under constraints imposed by the other side of the mirror, the ‘classical model of beauty’. The poems in Boscombe Revolution are perfect at subtly highlighting this and showing that such problems are far from over.