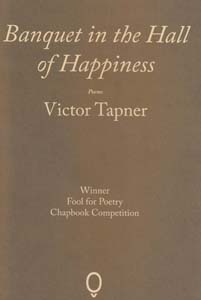

Banquet in the Hall of Happiness by Victor Tapner

– Reviewed by Roisin Kelly –

Victor Tapner has already had several poetry collections published, so Banquet in the Hall of Happiness (a joint winner of the Fool for Poetry Chapbook Competition 2015) is hardly a novelty for him. For those of us who are coming to his work for the first time, there is plenty of originality and inventiveness to be found in this chapbook, which does what comes with natural grace to Tapner’s writing: it presents us with new ways of looking at the world.

Take the opening poem, ‘Kalashnikov’. Comparing a rifle to a woman could have become grim and seedy in the hands of another writer, but although the Kalashnikov is described as “promiscuous and unashamed”, “stroked by many hands”, it is infused with an agency of its own. The poet achieves this by letting the rifle speak for itself. It inhabits a surreal, twilight world, moving between a hiding place in a quiet suburb and waiting for daybreak in the rubble of an apartment block, “cradled in rough arms”. The rifle refers to its many lovers, with a hint of gentleness towards one previous owner, “the corpse of a boy” that the rifle lay with for hours before it was discovered. However, it it is In the closing lines that the Kalashnikov’s autonomous power and independence is truly asserted. At the grave of someone described as merely a “one-night stand”, it is fired in salute:

It’s at such times I laugh. Head raised,

I cackle at the heavens. I feel no loss.

Tapner is poet of place as much as anything else. From the Kalashnikov’s ruined city we come to the Orient Hotel in an unspecified country, where an ambassador and his wife are taking afternoon tea, as per the title. It’s so very (presumably) British, which turns out to be the point of the poem. Whereas the Kalashnikov inhabited the quietly surreal, devastated landscape of war, here we are invited to a space outside of such gruesome happenings. Ferns stir in the air conditioning, cocktails are poured, “Hemingway, Coward, Nehru, Mountbatten” are immortalised on the wall, and smiles are “as light / as […] lemon cake”. The author need say nothing about the dark syrup of colonialism that is surely rising through the floor of the Siam Lounge. Each delicate, air-conditioned image speaks for itself.

A universal empathy towards those who make their way in this world however they can is the chapbook’s overriding emotion. In ‘Girls With Sideburns’, the narrator allows her legs to be shaven by her client in his hotel room before he puts a white towelling robe around her: “It was like I’d gone to live in America”, she says with an unexpected sweet naivety. As cool air drifted through the Orient Hotel in the previously-mentioned poem, here the sprinklers are “cooling grass” while the narrator is fed oysters and fruit. Tomorrow she’ll be back on the beachfront, again plying her trade with the other “girls with sideburns”, who also happen to be skilled in the art of concealing their bruises. The man who peels a pear for her, and the Orient Hotel’s ambassador and his wife, are creatures from another world in this context. But, Tapner reminds us, this is the world we all must live in, one way or another.

His empathy is not limited to those less fortunate; a gilded prison is still a prison. ‘Banquet in the Hall of Happiness’ is written from the perspective of China’s Empress Dowager Cixi, who takes her meals surrounded by silent eunuchs. It is forbidden to touch the “woman made Buddha”; her maids wear white lace gloves when they change the empress’ gown for her evening walk. Although she herself is “[f]orbidden by rank / to smile”, Cixi finds escape from the mirrored hall in the sensuality of her meal. In the way she walks for pleasure in the marigold garden at dusk, she peels an iced lychee “for its scent” and to see, in contrast to her own whitened face, “its skin red as a berry”.

Different places and people surface throughout these sixteen poems, and Tapner wastes none of them. ‘Dead Sea’ places the poet at the “world’s lowest point” where he and a companion lie on sunbeds beside the salt-lake that can trick “migrating flocks into stopping / for the cruelest drink”. Tapner still manages to find beauty in the harshness of the landscape, describing the growth that occurs after rain, when “Shulamit’s Hair” thrives beside waterfalls, and the sea “is flushed as bacteria bloom”. This is how he finds a way to speak about the damaged relationship at the heart of this poem, and about the healing of something damaged even if the cure is as impermanent as the greenery that the rare rains bring.

My favourite poem is ‘Outback’, in which Tapner describes another unforgiving landscape, where desert meets sea. It’s fearful and dangerous despite its bleak beauty: scorpions and spiders are waiting below the rocks, and he is tormented by sandflies in a place that some people have said “is close to paradise”.

Some mornings I sit on the rocks

and watch young sharks

circling in their nursery offshore,

wondering how they judge

when it’s time to leave

for darker waters.

Like Tapner, I too have tried to write about looking at the sky from a different perspective on planet Earth. He does so more beautifully than I could. As night falls over the desert, he looks up at a sky in which someone once pointed out the constellations to him, back in their “safer world”. So far away from that person, that word, and the familiar night sky above that hemisphere, he now has “a whole galaxy to decipher”. The implication is that this will be a lonely and arduous journey. But after reading this chapbook, I believe that Tapner will be irresistibly drawn to the discovery and deciphering of countless new galaxies.