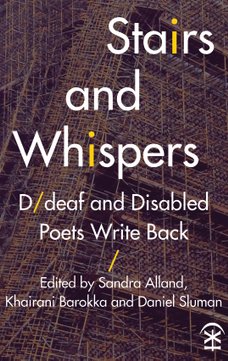

Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back, ed. by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka & Daniel Sluman

– Reviewed by David Mitchell –

It would be impossible to provide an honourable mention for every poem and performance I enjoyed in this skilfully-edited anthology, which these few words can’t do justice to. Stairs and Whispers offers 260 pages of quality poetry, essays, links to YouTube videos and soundcloud performances. Despite being subtitled ‘deaf and disabled poets write back’, deaf poetry is only a modest percentage of the work featured, which explores a spectrum of physical and invisible disabilities. The editorial highlights the intentionally inclusive nature of the book, and the depth of work by authors of varying self-identifications, orientations, cultures and ethnicities powerfully demonstrates that disabilities do not discriminate.

This book challenged me in ways I was not expecting. I come from an era before political correctness, an age of compulsory brave faces, stiff upper lips and false bravado. Or, as Georgi Gill skilfully puts it, “overcome the odds… or accept failure and be ill quietly.” This book measures modern attitudes within an array of disabled communities, and sadly, the discrimination and marginalisation it describes are still very real.

‘The stars are maps’ by Gary Austin is a wonderful BSL (British Sign Language) poem, presented as a short film in which a signer performs to a silent soundtrack, as words and images appear on screen. The movement of a boat becomes hypnotic, as waves rise and fall. The already powerful poem is joyfully enhanced, thanks to the signer’s performance. All the short films were a pleasure to watch, and Jackie Hagan‘s poem about a day in a ward for the mentally ill was moving and wonderfully performed. She is a poet I am keen to revisit.

Many poems are accompanied by links to audio files. Cathy Byrant is on fine anarchic form with her poem ‘Ms Bryant is Dangerously Delusional’, comprised of statements either said or written about her and her partner Keir. I recommend listening to its accompanying live reading. Kier (presumably) is the muse for Byrant’s sweeter poem ‘To my Non-disabled lover’, which celebrates the love that a carer gives, ‘Greater than the la la love of flowers… the hand, fluent with anger, filling in forms.’

‘Disabled Woman Swimming’ by Miki Byrne takes the reader, step by step, on a journey of perseverance, then lets them share in the joy of weightlessness: ‘Released from her body’s own drag, the euphoria of buoyancy lifts her’.

Resentment of prejudice and austerity are recurring themes. Disabled people face employers and educators concerned with what they can’t do, and health assessments obsessed with proving they could be doing more. There have always been exceptional writers and poets producing quality work while managing visible and invisible disabilities – Christy Brown, Lord Byron, Ian Drury and Sylvia Plath being just a few notable examples – and these people who can write back represent a larger community who suffer in silence. For me this anthology’s strength is that it contains an array of exceptional poets and writers sharing work relating to modern experiences of disability. Promoting contemplation and conversation, it should be added to Special Educational Needs courses and British Sign Language classes, and would be a worthy edition to any library shelf. It contains celebrations of life and humour amongst the sorrow, tackling the issues affecting deaf and disabled communities in a brave, mostly positive, always revealing and often insightful way. It reminded me in some respects of last year’s The Good Immigrant (ed. by Nikesh Shukla), and should be posted to politicians and available on the front tables of every major bookseller in the UK.