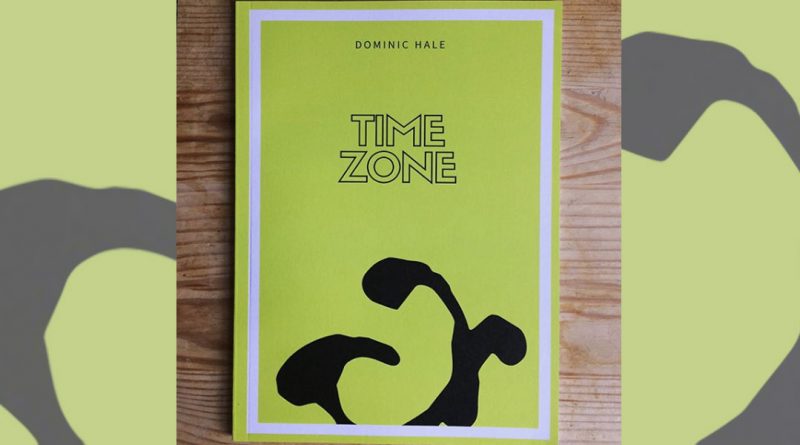

Time Zone by Dominic Hale

-Reviewed by Alice Tarbuck-

Dominic Hale’s new pamphlet from Spam Press begins with an epigraph from Jack Spicer: ‘A poet is a time mechanic, not an embalmer’. And in Time Zone, Hale certainly is a time mechanic – one who takes a good look at time, kicking its corners, sucking his teeth and declaring that it will be very expensive to fix. He turns his eye to our contemporary moment, and thus Hale’s work joins the body of work that responds, seemingly in real time, to contemporary crisis. Olivia Laing’s Crudo is perhaps the prose equivalent, constructing and reflecting on similar claustrophobias and information overloads. Hale’s work, however, is so close to the coal-face of unfolding events that it reads like a series of staccato reactions, declarations, thoughts that begin, form, and unform in the space of a few lines. ‘Pass me the scalpel, Monsieur Hacktivist, and split the plinth’. Hale investigates the internet, the media, and the art of internal line-rhyme, and a million jokes of the kind you think of at 3am and shout to someone at a party. The poem – for it is one vast single poem – reads like a scrolled-out, small-hours stress hallucination, and it is wickedly funny.

Hale’s language is fizzing and joyful, and despairing. It carries its glib sarcasm into moments of sincerity and out again. It is as if BBC News and Tumblr kissed at a party. ‘Make me the Vogue ogre/Soak me in iconic votes./Last past each of them, sweet Princess Peach’. The broad spacing and full stops ask that we take every line alone, that we give each its weight. But the joy of the work is in its accretion, and each line sings to and sinks into the next, forming novel relations that never quite solidify into anything certain. Hale’s ear for the registers of contemporary news and culture makes the reader feel as if their ears are open to every media feed in the world simultaneously. Calling up the invocations of epic, RuPaul’s drag race (or at least drag vernacular), systems of democracy and Princess Peach, glamorous female of the Super Mario games. Amongst this overwhelming noise, discrete themes emerge – profound distrust of the effects of the internet, a concern for climate change. The two are important in the way they speak to one another: the spurious anxieties of the former seem to repeatedly obscure the urgency of the latter.

This is a pamphlet that embodies urgency and torpor and seems to speak through, and about, screens, how our brains relate to information. It is a real delight to read, and particularly to read aloud, because of the chewy jokes, rhymes and the sheer pleasure in language as fun and clutter that Hale brings to it. Masterfully oscillating between the throwaway and profound – it takes a great deal of skill to balance the two, and bring them into productive relation. Hale is a brilliant time mechanic, and he bends and re-shapes time in ways that satisfy, terrify, and entertain.