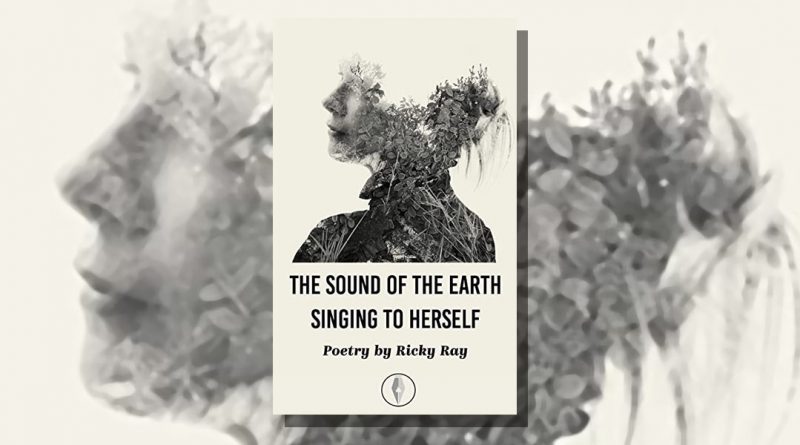

The Sound of the Earth Singing to Herself by Ricky Ray

-Reviewed by Marie Isabel Matthews-Schlinzig-

At the most basic level, we are all creatures of the Earth’s making. If we think of other living things as kin, the differences between us and ‘them’ become porous: membranes allowing connection, transfer, even transformation. The resulting changes may not be of a physical kind; rather, they are taking place in and through our creative imagination. Let’s, for instance, gaze at the world through the eyes of other living beings, and examine how this affects our image of the ‘other’ as well as of ourselves.

It is these connections and transformations of perception as well as thinking, which are the heart of Ricky Ray’s pamphlet The Sound of the Earth Singing to Herself, published with Fly on the Wall Press. A distinct voice speaks in and through these poems. Gentle, straightforward, intense. They tell of experiencing life in and through a body shaped by disability: ‘and by comfort I mean / pain | that relents / from a knife-twist | to a dog gnawing’ (‘What’s Left’); of the intimately felt companionship, even brotherhood, with other creatures, particularly dogs, as well as plants: ‘My kind have rough barks, trunks, and a desire to hold steady’ (‘A Walk in the Woods’). They speak of nature and creation, and human estrangement from both (as in ‘Somewhere in Indiana’); and, especially toward the end of the collection, of impermanence and death, which are embraced as a natural part of the transient existence we lead (as in ‘Read Slowly’).

Ricky Ray’s poetry reminds us that everything is connected, down to the moths eating away at ‘My Favorite Sweater’: ‘a thread of wool raveling into a thread of moth | the moth’s wings the stitchwork of the hand that knits us all’. What we need to do is pay close attention, open ourselves with true empathy, and be ready to think differently. That is what Ricky Ray’s poems do in themselves and it is also the effect they have on us as we read them. They shift our point of view from that of one subject to another, often looking at the individual as well as the world from a distance, be that a physical, temporal, or psychological one. Thus, they make us read, for instance, our existence as written into and by our bodies, which at times seem to lead a life of their own (‘We Carry More than We Can Tell’).

What Ricky Ray’s pamphlet finally drives home is the understanding that such shifts in perspective are essential: because they might (just might) save us, by helping us see how disrespecting and destroying the Earth is an act of self-destruction: ‘For when the birds dry up || and the trees choke […] | and the oceans burn off | […] the Earth will still be here, singing her duet with the sun.’ While lines such as this sound apocalyptic, they also, albeit wistfully, breathe with the beauty of life. As do all of Ricky Ray’s poems, while at the same time buckling under the awareness of the current state of the world, and of the – to the poet observer in these poems – often inexplicable character and behaviour of the human beings in it.