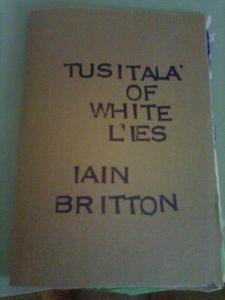

‘Tusitala of white lies’ by Iain Britton

-Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey-

I was interested in this chapbook, by a New Zealander, because of the potential of its culturally different image-base, approach and perception, and also because the physicality of the chapbook is satisfyingly aesthetic.

Immediately, the title arouses curiosity. What is Tusitala? It is, Google advises, both the name for a spider, and the Samoan word for a storyteller. So we have the exotic element immediately, as well as a provocative theme.

Visually, the poems are experimental, with lower case, forward slashes, spaces, etc., laid out in meandering, double-spaced lines for the most part, with the exception of the last section of the final poem. The titles attract with their strangeness: ‘extravaganza’, ‘the last lamp post in the world’, ‘tusilala of white lies’, ‘profile of a yellow circle’, ‘spiked’, ‘glass cathedral’.

The first poem, ‘extravaganza’, introduces sunflowers that ‘reflect what has been carefully given’, and inviting the reader to do the same. The word ‘extravaganza’ is lavish and rhapsodic and conflicts with the word ‘carefully’, creating an interesting disconnect. Part 2 of the poem introduces the narrator’s voice, who, rather than reflecting what has been carefully given, has:

‘been caught out

demolishing petals

and spitting sap

a Morpheus finger

pok(ing) holes in the afternoon’s somnambulating journey’

These lines increase the sense of a jarring disconnect, the violence of ‘demolishing’ and ‘spitting’ contrasting with the lulling mention of Morpheus, the somnambulating day, and I find myself wondering what effect the poet intended. The impact is muddied further with another less clear image:

‘the earth’s curvature

is a showcase of people peering

through red-frosted light’

The next stanza introduces ‘Hypatia’s theatre / of yellow hibiscus moons’. There’s a sense of underlying dissatisfaction or fear: ‘I risk losing a sea and all its singing companions / I risk the loss of purities’. Later: ‘I’ve been caught in the act / of being where I’m not wanted.’ Images recur, setting up the premise of motifs, and it’s up to the reader to work out their symbolism, for instance, in this repeated image of the earth as a ‘showcase’:

‘the earth’s a showcase

in a fat man’s skin.’

Of course, we all actively seek meaning in what we read or see. We hope there is some meta-construction in the mind of the narrator, and these are not just random images haphazardly thrown on the page exquisite corpse style, to create an impression of obscure poetics. Here we find that these often beautiful images do accumulate to suggest a morbid disillusionment with life.

In ‘The last lamp post in the world’, I am reminded of aspects of Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock – the pointless waste of time, the inexorable movement towards an ending, without anything having been accomplished:

‘often enough it’s a creeping

paralysis

an advanced decrepitude /

or exposure’

the pendulum shifts:

‘from one foul breath to another’

We move from the lamp post, to vineyards:

‘…owned by women

who drink the earth dry,

dig in the carcases of their mothers,

and their mothers’ mothers

their fathers too’

and then the pendulum shifts again to an island where:

‘the women plump up

in summer

shoot botox shoot sun-tan serums

inflate smiles’

Having set up a mood of hostility towards certain women, the lamp post begins to gain in symbolism as it:

‘shifts its gaze – stares blindly

its back has been broken then straightened then broken

the air

seems artificially sweetened’

The tension of these images effectively culminates in the final stanza:

‘I feel the rain

the wind’s nerves

the sky chewing on a power line’

Throughout the chapbook, I am looking for the ‘white lies’ – in ‘celestial presentations’, in the ‘supermarket’s optimism’, in ‘the room we call home’, in cradle rhymes, in the ‘flavoured’ future, even in intimacy. But these are not clarified.

In a number of poems, the narrator appears homeless: ‘the river uses me as a thoroughfare’; ‘I’ve come to a bed where itinerants sleep’; ‘fur coats of grass/are readily affordable/for the scrabbling hungry’ – hungry not only for food (a number of times, food parcels are mentioned, knives and forks, a table, consumption) but for spiritual nourishment: at the font in the glass cathedral, ‘now’s the time…for the mouth to tell the truth’.

The title poem begins with a potent image of nature fighting back against the ‘white lies’ of society, of the church:’a million blackbirds / fling full stops at the horizon’. As in a kind of Prufrock, there is a series of characters. Who, the narrator asks himself, does he believe?

the lady in black feathers

who owns and occupies a fig tree

or the slothful bugger

who lives in the letter box

…..

or the toilet roll author of Kingdom Street’

The reader is also invited to consider whether to believe the narrator himself. He is, he tells us: ‘the tourist guide bus driver jesus janitor / the son reorganizing the future footprints of a family yet to cement its language in stone in grubby layers broken like old teeth’. Perhaps he is the tusitala. Perhaps there are many.

As for who the narrator will believe, he decides he prefers:

‘the brunette

her feather cloak

her moulting shadow her strut’

It is escapism the narrator’s looking for, an ‘astral flight / with no strings dangling’.

The language of this poem is arresting, but non-specific and contradictory, as the narrator retreats ‘into the hood of my consciousness’ while at the same time

‘groping for the lady’s

anatomy

her tightening grip – this flesh

and blood

mix of polarities’

While the rest of the chapbook has many imagistic high spots, however, the last poem, ‘glass cathedral’ has a few ‘ouch’ moments:

‘my ribcage’s not for hire

the thistledown’s

not there for the privilege of matting-up

my groin’

This final poem is six pages long, but the last two pages suddenly change, from the same form as the rest of the chapbook, to a Joycean stream-of-consciousness prose. This compression might have been intended to intensify the content, but instead, it simply jars visually. The message does end on an apparent note of hope, but while the beginning of the poem instructs us to ‘tell the blackbird’ the final instruction is to ‘tell the bald eagle’.

While there is much in this chapbook that is intriguing, the overall impression, unfortunately, is of a collage of ‘murky elaborations’ drip-fed onto the page. As a reader, I find myself struggling through these inconsistencies, sometimes tripping, sometimes falling. Certainly there is an assertive voice here, but while I’m all for visual poetry (and many of the images do have power), ultimately, I feel I’m in a mudbath of images which blur the overall message.