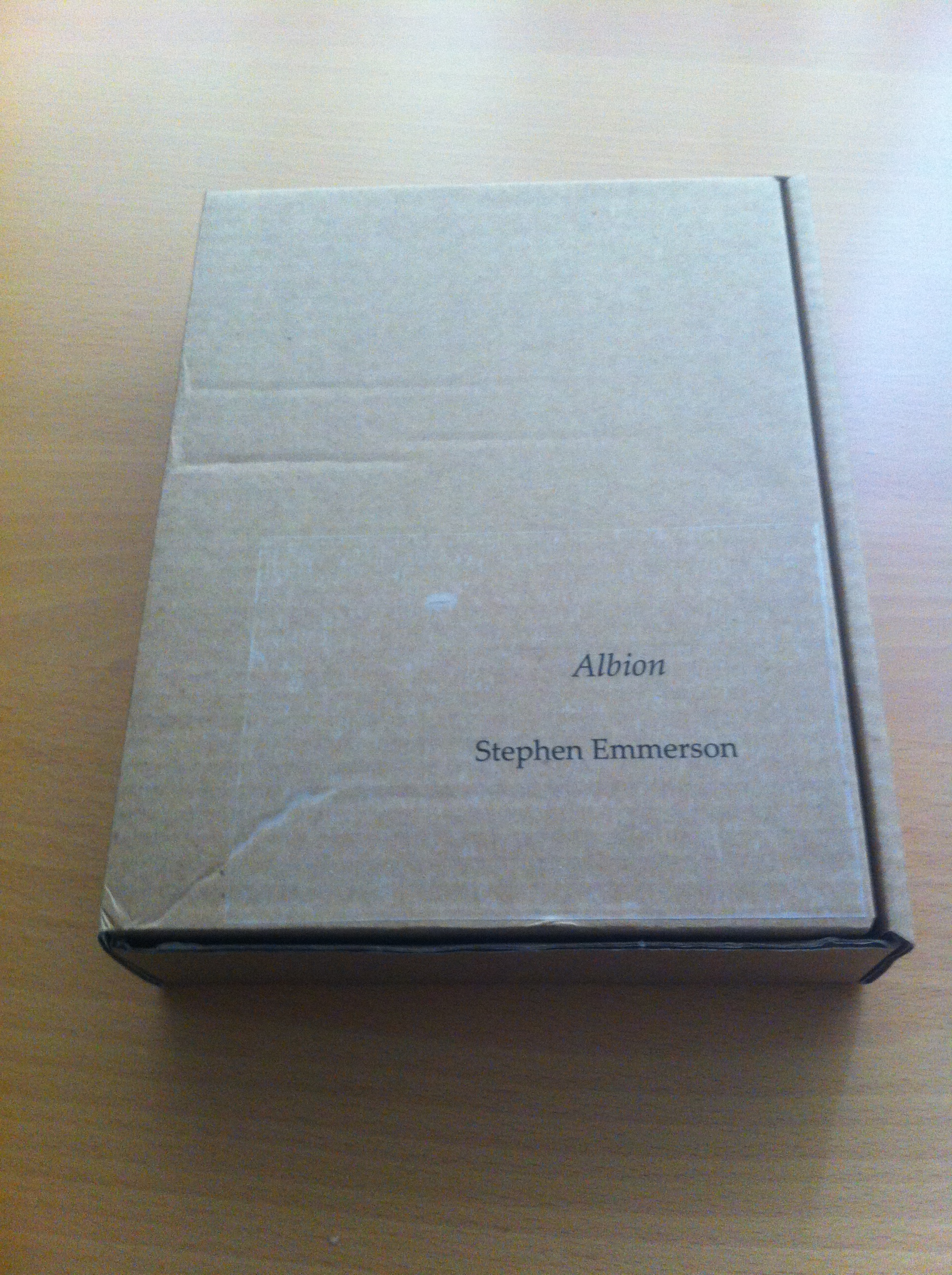

Albion by Stephen Emmerson

-Reviewed by Paul McMenemy–

Albion is the product of an artwork installed by Stephen Emmerson in Inland Studios, South London over two days in August 2012. Five typewriters were arrayed at the points of a pentagram drawn in the middle of the gallery floor, with names from the Blakean mythopoeia written in front of them. On the walls hung four “visual poems” – black and white arrangements of typewritten capitals, pencil and biro marks. A specially-written soundtrack looped in the background. On entering, participants were given printed instructions: “Please use the typewriters to help create a new poem by William Blake. // Write whatever you want.” Below this was a half-page “introduction” giving a brief, selective précis of Blake’s work and an explanation of what Albion was intended to be: “a poem-installation based on psychogeographical information and psychic and paranormal investigations that explore Blake’s complex methods of composition and mythopoetics. It is also an attempt to reconnect with the political aspects of Blake’s work.”

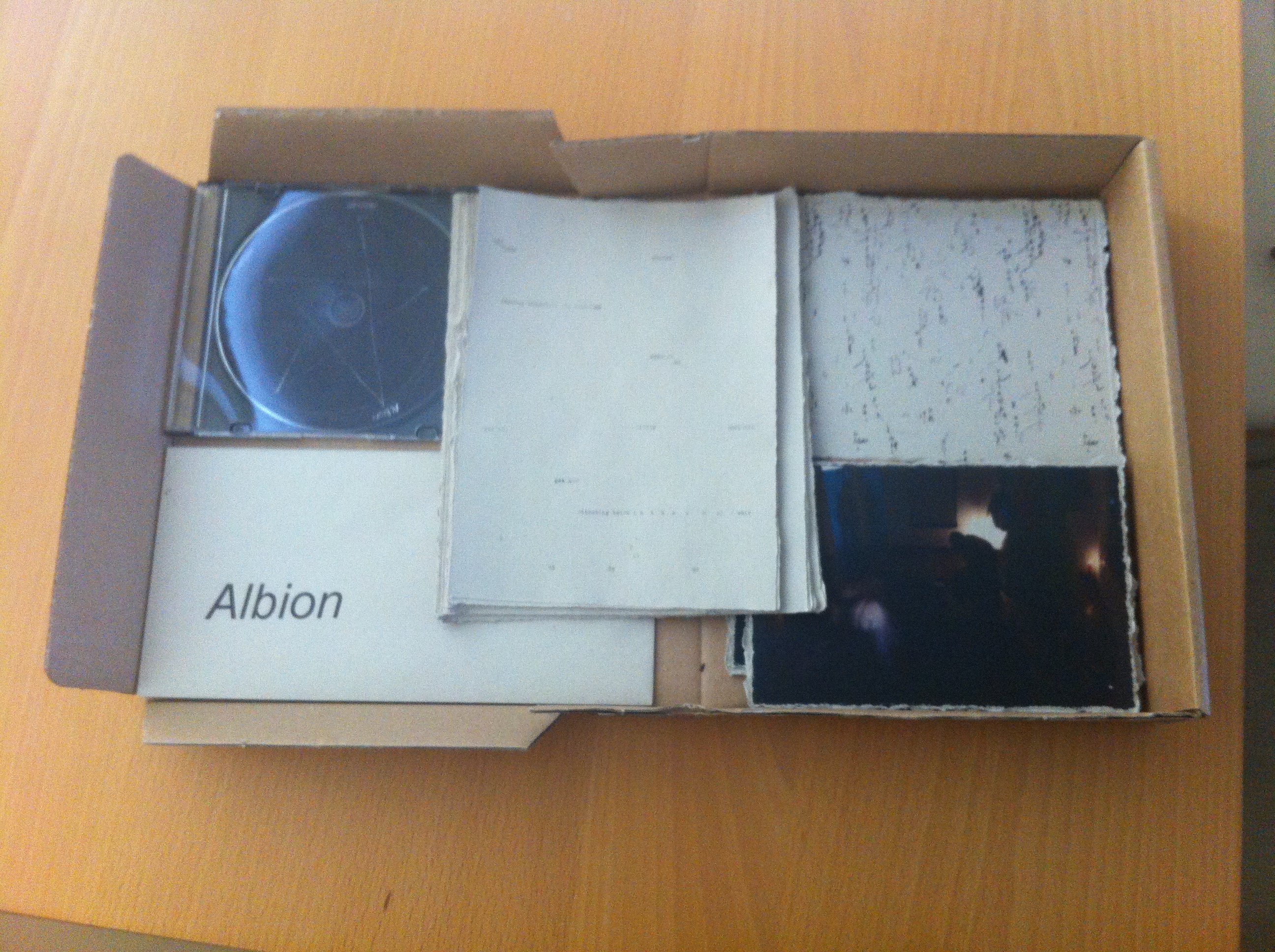

The interest of Albion, the “poem-installation”, lay in the process, not the product. This is justifiable in an installation, but problematic in a poem. Consequently, Albion, the published artefact, reproduces as much of the installation as will fit in a hardback-sized box: the reader is given the instruction-sheet, the “visual poems” and six murky photographs of the installation for reference, and is advised to listen to the soundtrack (best described as “art installation music” – a polite industrial magnolia noise of strings and typewriter clacks) on CD whilst reading. Ideally, all this should prepare a sort of spiritual static, through which the poem can break like longwave radio.

Blake’s “new poem” (as dictated to his psychic typing pool) comprises 22 loose, roughly-cut, roughly A5 sheets of homemade-looking paper, each side of which contains some typewritten text. The typewriters provide another layer of interference – as well as the games that can be played with spacing and overtyping, there are the accidental effects of ineradicable typos, worn keys, dry ribbons, etc. However, text written in 6pt grey type on grey paper needs to be worth the eyestrain. It is a commonplace that those who want to write should “just write”; anyone who has ever followed this advice will recognise its results. Albion is 44 sides of blue-sky writing, apparently unedited – there are a couple of black marker redactions, but by whom they were made, when, and if these are the only excisions is unclear. We are also not told who (apart from Blake) wrote Albion – was everyone who visited invited to contribute? Did Stephen Emmerson play any role after providing the conditions under which it could be written?

The questions arise because while Emmerson has presumably spent plenty of time thinking about Blake, psychogeography and the other things mentioned in his introduction, there is little evidence that anyone else involved in Albion’s writing has. If one is describing something, however fancifully, as a new work by Blake, one must explain in what way this is the case. Even if we accept the dubious notion that Blake would decide to disregard his writing style and most of his pre-existing symbolic idiom, why would he replace it with prose of the sort written by teenagers who have just read Ulysses and have not yet realised that stream of consciousness is a style, not a method?

There is the odd interesting underdeveloped idea, but there is only one page that engages with the remit in any detail. It begins:

“This ghost of a dead typewriter

A vision of the sun of albion

Luvah weeping by the thames

Asits chartered water pass by

“Urizen loom loftily appo ite

Surveying the Scene, parcelling,

It up in consciouSneSS. But one

Sacred letter reSiSts hi gaze” [sic]

It is entirely atypical of the whole. I cannot say it was definitely written by Emmerson, nor that it was written, or gestated, in advance of or after the installation (while it feels more “composed” than the rest, it also makes a feature of the typewriter’s worn lower case “s”, which suggests spontaneity), but if one compares it to the previous page, which reads in full:

“DOULTOID Said the money bank

FALLAN criclking pallour and argent

COMMEN crieo eeioldemmeraldinth and

AD SO SAD GO HOME SOME”

one may see what I mean. Of course, this being a book in a box, presumably the pages can be read in any order one likes, but would it follow any better on this page:

“Hercules and diogenes walk to the cafe and order beans on toast and hash browns.

the sun makes their eyes hurt so they wish they had unglasses

“the beans taste d lik they had been sitin in the fridge for weeks

absorbing the smells of everythingaround

“hercules felt quite sick”

or the page which is a line of letters over which further letters have been typed making the whole illegible?

Typewriters might produce visually interesting results, but within the context of Albion’s conceit they present a difficulty: although ancient technology for most of Albion’s creators, they might as well be iPads for all the relevance they have to Blake. It could be argued that the physical act of imprinting ink on paper with metal provides some analogue to Blake’s practice, but it seems unlikely that the engraver would have appreciated the imprecise effects produced here. So again: what has any of this really got to do with Blake? Would this experiment have had any appreciably different outcome installed in North London in an unadorned room, the only soundtrack traffic and gallery-goers, Blake uninvoked and participants simply asked to sit down and type?

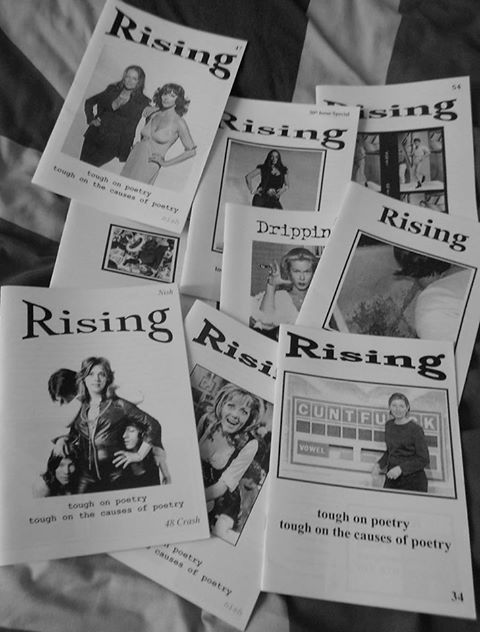

Of course, with no overarching concept to justify it, as an installation that would not have worked – which shows up the central confusion of Albion. Like This Press are attempting to sell the experience of two days last summer in a gallery in Camberwell, as so many pieces of paper. The two are different things: Albion may have worked as an installation; it does not as a poem.