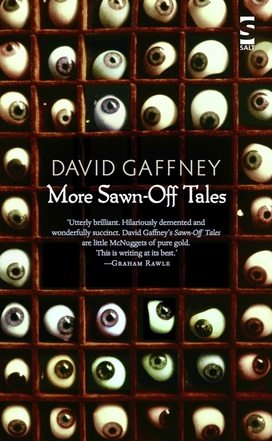

‘More Sawn-Off Tales’ by David Gaffney

-Reviewed by Ralph Jones–

Short, Sharp Bursts of Weird

Give David Gaffney 150 words and you’ll be holding his hand as he leads you to some very strange places. More Sawn-off Tales is the second in the writer’s Sawn-off flash fiction series and this collection comprises 73 disquieting stories, each exactly the same in length. Whether describing using crossbows to hunt sheep, or the sound of bass-heavy techno killing an alpaca, Gaffney’s prose carves out a place in the weird corner of the room and doodles contentedly all over it for the afternoon. His miniature stories, creepy and amusing in equal measure, are a glimpse into a hive of the uncanny.

It must be said of the author that through his collections with Salt he has managed to bring the appealing medium of the tiny story to a much wider audience. Nestling snugly between poetry and conventional short stories, flash fiction deserves the ‘iPad generation’ moniker it has attained. There seems something intrinsically modern about the form (its National Day came, after all, only in 2012) and Gaffney can claim to be one of its most skilled practitioners. In a period in which, to a greater extent than ever before, fiction vies for attention with many multifarious forms of entertainment, flash fiction could well be one of modern literature’s real success stories. ‘No one had a job because everybody made their own things with 3D printers’, Gaffney writes of the future in ‘It Doesn’t Really Matter if Things Die Out’. It is only a mild exaggeration.

First, though, a reservation. In part because they are so short, the stories fall victim at times to various ailments. ‘A Dress Code for Modern Musicians’, for example, feels like a list rather than a narrative; ‘It’s All in Storage’ seems set on a stage only a much longer story can fill; and ‘Let’s See What Rachel’s Been Up To’ is simply too heaving with bizarre references to care much about. It would be intriguing – and, more than that, sometimes necessary – to hear more about the inhabitants of some of Gaffney’s stories, and for this reason the confines of the format serve occasionally to restrict rather than purify the writing. Not the worst criticism for a writer to receive but a reservation nonetheless.

There is so much to enjoy in the writing, however, that the duds don’t leave much of a stain. It is an absolute pleasure to read some of the imagery and allusions with which Gaffney peppers his work and he frequently exhibits a turn of phrase that is simply enchanting. We are treated to lines like ‘You are so bold with cobalt, Terence’ and ‘Izzy removed her clothes and crept towards me like a foal tiptoeing through the snow’. Gaffney knows how to paint a powerful picture and does so time and time again: ‘suddenly my anus became a gaping, gelatinous mouth and the tube wormed up inside me like a long, thin girl swimming up a pipe’ is a sentence Carol Ann Duffy mightn’t be brave enough to set down in print.

Several stories stand tall above the rest as particularly effective syntheses of the comical and the bizarre, or the strange and the profound. ‘The Joke About Todd Pokato’, for example, is sublimely funny; and ‘The Building with the Hole’ offers one of the collection’s most touching lines: ‘she said sunshine was like a friend: at its best on first meetings and farewells’. Shades of Luke Kennard loom into view in some of the pieces – as, for example, in ‘Listed Bridge’ (‘I was able to climax only with the aid of a physical theatre company’) and ‘Happy Birthday, Hee Hee’:

‘It’s not Jim’s birthday,’ Martha explained. ‘It’s just something we say around here.’

‘So what do you say,’ I asked, ‘when it really is someone’s birthday?’

‘We don’t say anything.’

Central to many of the pieces is the concept of borrowing or inhabiting others’ bodies and possessions (‘The Homes of Others’; ‘It Happens Inside’) and breaking up with partners or making fresh starts (‘Bleached Linen Number Four’; ‘Blood in Fight’). More often than not, characters in More Sawn-off Tales are unsatisfied with the hand they have been dealt and are looking for ways to shuffle the deck.

The afore-mentioned Izzy appears twice in the collection, on both occasions able only to have sex under certain strange conditions. Indeed the tales show evidence of a writer preoccupied with not just the bizarre but the sexually perverse: we are witness to fetishists having sex with eyes; a member of a theatre troupe being plastered to a wall with semen; and a couple booking a viewing of a property simply to have sex in it. Is Gaffney visualising a world in which these fixations are commonplace, or hinting that they lurk at the bottom of this one, unacknowledged and suppressed?

Eyes are a subject to which Gaffney returns with macabre relish; a search for the word indicates that it is included 28 times, and indeed 42 of them adorn the front cover of the book. In one story he discusses their transportation, and in another contemplates the logistics of implanting those of an ex-girlfriend into those of a current one. The ‘thorough and professional’ eye of his proofreader is credited at the beginning of the collection but this rubs salt in the wound when it becomes apparent that at least three errors seem to have escaped her grasp: the misspelling of ‘alpaca’ in the title of ‘DJ Stinger and the Ghost Alpcaca’; a character in ‘Blood in Fight’ being called first Maria, then Marie, then Maria again; and inconsistent title formatting. Small oversights, perhaps, but noticeable ones in stories of such brevity.

‘A Dress Code for Modern Musicians’ causes the book to limp out slightly but it has walked so tall thus far that it matters little. By the time one has finished reading Gaffney’s collection one is living deep in the midst of his strange creation, wondering why not everyone in the real world behaves in the same fiendishly weird manner. It’s not that they shouldn’t do so; it’s just that if they did, Gaffney wouldn’t have released More Sawn-off Tales. To escape into his imagination is an experience no amount of 3D printing can replicate.