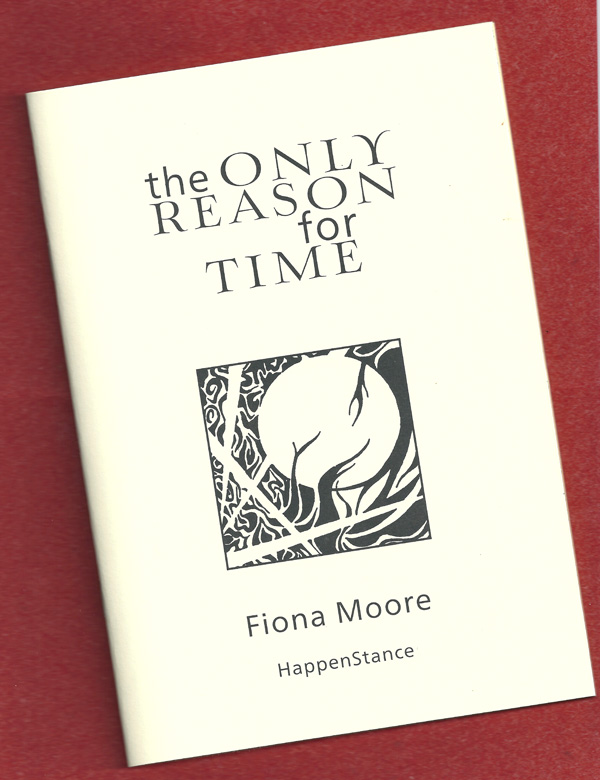

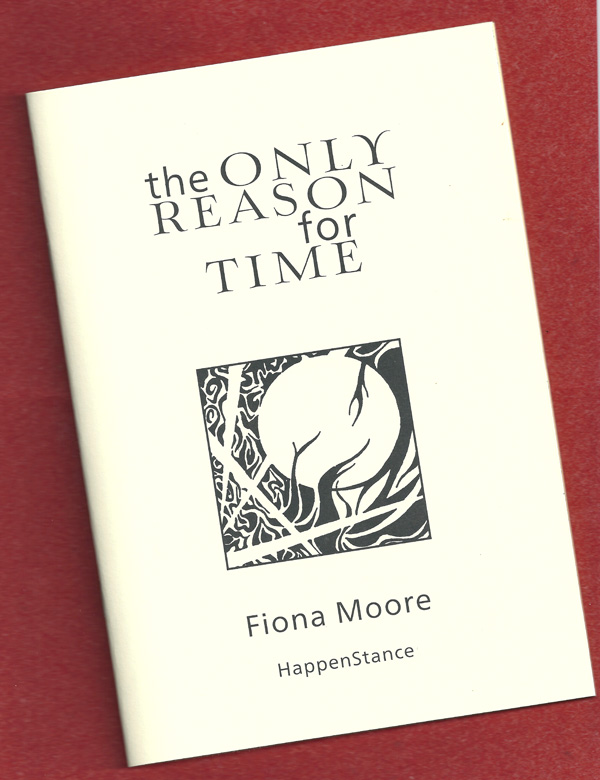

‘The Only Reason for Time’ by Fiona Moore

-Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey–

After the premature death of a lover, it would be easy to succumb to a tidal wave of bitterness and anguish. But, unlike Auden’s famous ‘Funeral Blues’ poem, where, in a rapture of grief, he exhorts the world to ‘stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone’, Moore is more private in this chapbook, addressing not the world, but her absent lover: ‘Your death kills me a thousand times, / the tyranny of repetition’ (‘1010101010…’). Like Auden, however, her world has slammed to a halt.

The radiance and gravity of the poems grow out of volcanic emotion, channeled into strict forms, creating a poetic experience of grief. Everything is pervaded by her partner’s absence, poignantly symbolized by his Aran jersey, which she wears, but ‘which holds me differently’. The shirt, which a medical team had to cut off him, and which she found bundled in a wardrobe months later, is another symbol: ‘a shirt for a gentle hug’, now ‘slashed through’.

In both tone and content, Moore’s poems are layered with sub-texts and juxtapositions. Her attention alights at times on the cosmos, infinity, and also on mundane objects that have gained a resonance – the grey metal latch of a gate, a padlock, the clatter of change in a pocket, the stainless steel of a kitchen sink.

While her palette is muted for the most part, we see a flash of colour in ‘the white/purple bleed of petals in ‘Eden’, and in ‘the flaming/ orange, purple and fuchsia red of an Irish hedge’ in ‘Third day of fog’, suggesting natural erotic instincts that have been repressed through grief, leaving not only the landscape, but the speaker herself, ‘leached of colour’ (‘The distal point’).

The poems are imbued with an elemental grace: ‘O of the eye, the sun, the ocean, stopped by doors and windows and ceilings of earth’. Her soundscape is unobtrusive at first, but there is subtle internal rhyme, assonance and dissonance at work:

‘The water’s embrace jolts,

heaves, lulls me…I kick hard, breathing for you

through strands of hair…The drab land calls, the sea

spits me out – numb, dripping salt, living for you.’

(‘On Dunwich Beach’)

The moon is a recurring motif. In one poem she describes it as ‘a white-gowned eroticist’ and confesses: ‘I want to bare all for you.’ It’s probably no accident that the three moon poems are all written in three-line stanzas and hint at frustrated erotic desires: ‘my usual despair, worn out by night after // long night of nothing.’

Moore’s grief is solitary, with only the moon and the ghost of her lover for company. Even the cold, implacable sea, into which she plunges, ‘swimming for you’ spits her out again. She sees her partner in the leafless trees ‘whose outlines are all gesture’ (‘Overwinter’). The skeleton of the fish on her plate reminds her ‘of the last time we ate mackerel together.’ Poem after subtle poem reveals the significance of small events, set against the shadow of death.

In the title poem, she gives in to a fantasy that time might not be linear but looped, so that her partner who ‘went out/ through it like a door … will come back in /before you left, and intact.’ Several poems touch on philosophical, though not spiritual, observations. She is earthed in the natural world, and her departed lover is simply a ghost lingering here, not in some other eternal realm.

There are a few moments of light relief, such as the glimpse of a cluster of nuns ‘like five pints of stout /just poured’ in conversation with a man, ‘mud on his boots’ on a country lane in Ireland (‘Truly’). Another is the leap of joy experienced at the sight of ‘Bullocks –’

…‘at a gallop–

all bunched up

shouldering each other

muddy rumps rocking

up/down, hooves

thundering, rope-tails

flying…oh, the rain

roars for them’

This energy and momentum contrasts with the otherwise stopped-time sense of her emotional state. But it also suggests that the speaker is not yet finished with living.

Moore’s strength lies in her close, concrete observation of happening events, and in her perspectives. In the most dramatic poem, ‘What kind of sound crowds make’, when a child’s head is trapped between the doors of an underground tube, she forensically compares the collective ‘oh!’ gasps of the crowd to ‘the kind of sound crowds make / at executions of the surely innocent’.

There is a feeling of detachment and disconnection with the world, so when, in the last poem, she addresses the reader directly, it’s a jolt. Again, she layers the impact. We are made aware not only that we have been voyeurs to her grief, but that we too, have our own ghosts. Or, in fact, our ghosts have us: ‘You are the fire around which your ghosts are talking.’

But, as she writes wittily in ‘Hunger’: ‘One way to dispose of a corpse is to eat it.’

I am reminded of a beautiful poem by Matthew Dickman called ‘Slow Dance’ in which he says of his twin brother: ‘I know that one of us will die first and the other will suffer.’ This is something we all face. But even with this fear of impending loss, we wouldn’t do without love. This collection is not just a lament, but an ode – to the fact that the intensity of grief has been balanced by the joy of an earlier, equivalent love.

A profoundly heart-wrenching, spare and beautiful chapbook.