Rumpelstiltskin’s Price by Susanne Ehrhardt

-Reviewed by Claire Trévien–

A wonderful line in Susanne Ehrhardt’s biography states that ‘she had been living with the English language for twenty years before the first poem arrived’. This is a relevant fact not because, as she writes later ‘the odd mistake / lead me creatively astray’, but because foreigness of place, of tongue, of truth, are prevalent themes throughout Rumpelstiltskin’s Price.

The first section of the book, What is a Gamcha? is inspired by Ehrhardt’s time working and living in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa for various health programmes. Women are present throughout, united in their separation, as in the ‘women’s section of a crowded bus’, where each of the passengers is ‘locked in her skullful of noise’ but sway as one. Sometimes she deliberately points out their absence, or praises their inventiveness when faced with limited means. The Gamcha of the title turns out to be both everything (a scarf, a belt, a bag, a sling for your baby, ‘a sieve to strain your tea’), but also a ‘flimsy, faded, green-red checkered piece / of handloom cloth’. More often than not, Ehrhardt knowingly subverts our expectations of poetic tourism:

But a child with knees like growths

takes a hand, as orphans do,

laughs how squeamish we are:

you came to look, so look

before hitting the reader with the full horror of the situation:

they sit or lie,

naked skin on naked earth,

silent as the sky,

ask for nothing,

barely look up –

today’s and tomorrow’s dead

so alike one would have

to bend closer to tell

The second section of the collection Growing up German is very much concerned with aftermath, whether it is the state of postwar Germany, or the belongings of a departed mother. The title poem of this section is a powerful meditation on history. It feels particularly apt in a world where some politicians would try to have us remember WW1 as a glorious time for the British. Ehrhardt contrasts the soldier as a person with the soldier as a representative for Germany’s role in WW2. Her key strength is doing so in a way that doesn’t feel pat but fully embraces the complex and contradictory forces at work when reliving that episode of history:

Growing up when the killing was over,

the dead tidied away, we knew our history

as electricity is known, by its effects[…]

When our fathers died defending murder,

how shall we remember them?

Family relationships are also tense with the past, as with ‘German whispers’: ‘It’s history. There’s nothing safe to say’.

Throughout, there is a theme of storytelling: the stories a nation tells itself, the stories a daughter tells herself about a mysteriously absent father (‘For the next forty years, / you were the likeliest story told about you’). In the midst of this foray into the flotsam of memories and keepsakes is the most storylike poem of them all, ‘Rumpelstiltskin’s Price’: ‘it seemed unreal. / Not like this. Not like these warm limbs’.

Even in the final section of the collection, Exiting Sideways, storytelling continues to play a part, though it is less focused on the past than on imagining a potential ending. In its title poem, having narrowly escaped death in a car crash, Ehrhardt ponders ‘how curious, I’ve often wondered. So that’s it’ and on being alive today, tries to imagine herself dead at that moment: ‘Can I delete my steps, un-tell my stories, / erase my touch?’ In the final poem, ‘Facing the wall’, she takes this further, declaring that:

Soon there will be no tree, no wall, no eye,

no I or she; no slow or fast; no flex,

or pane, or room; no night or day

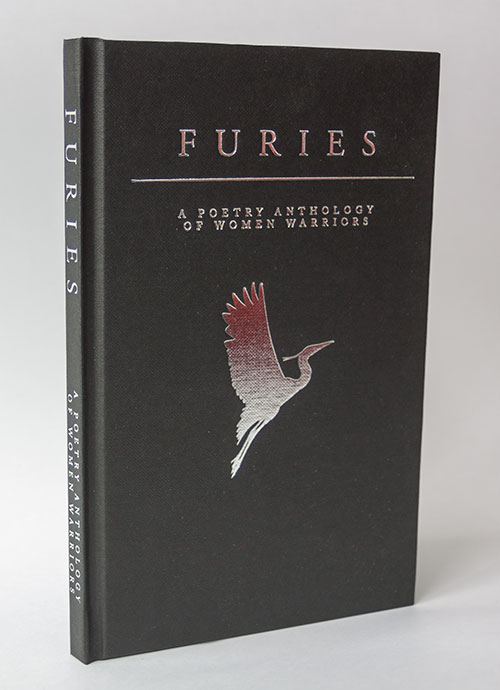

Rumpelstiltskin’s Price feels like a life concentrated into 82 pages, unrestricted by time or geography. It is also diverse in its choice of forms and voices, with an affinity for Ghazals in particular among the free verse. There is real pleasure in the sounds of language, as in the spread of plosives in ’Rondel’: ‘Rickshaws clatter over the broken tarmac, / scatter children, skirt a hawker’s display’, whose repetition gives a sharp snapshot of a street scene. Ehrhardt has the ability to switch from plainer lyrical poems, to a mode in which fairytales and existentialism happily mix. A well-deserved winner of Templar’s inaugural Straid Collection Awards in 2011.