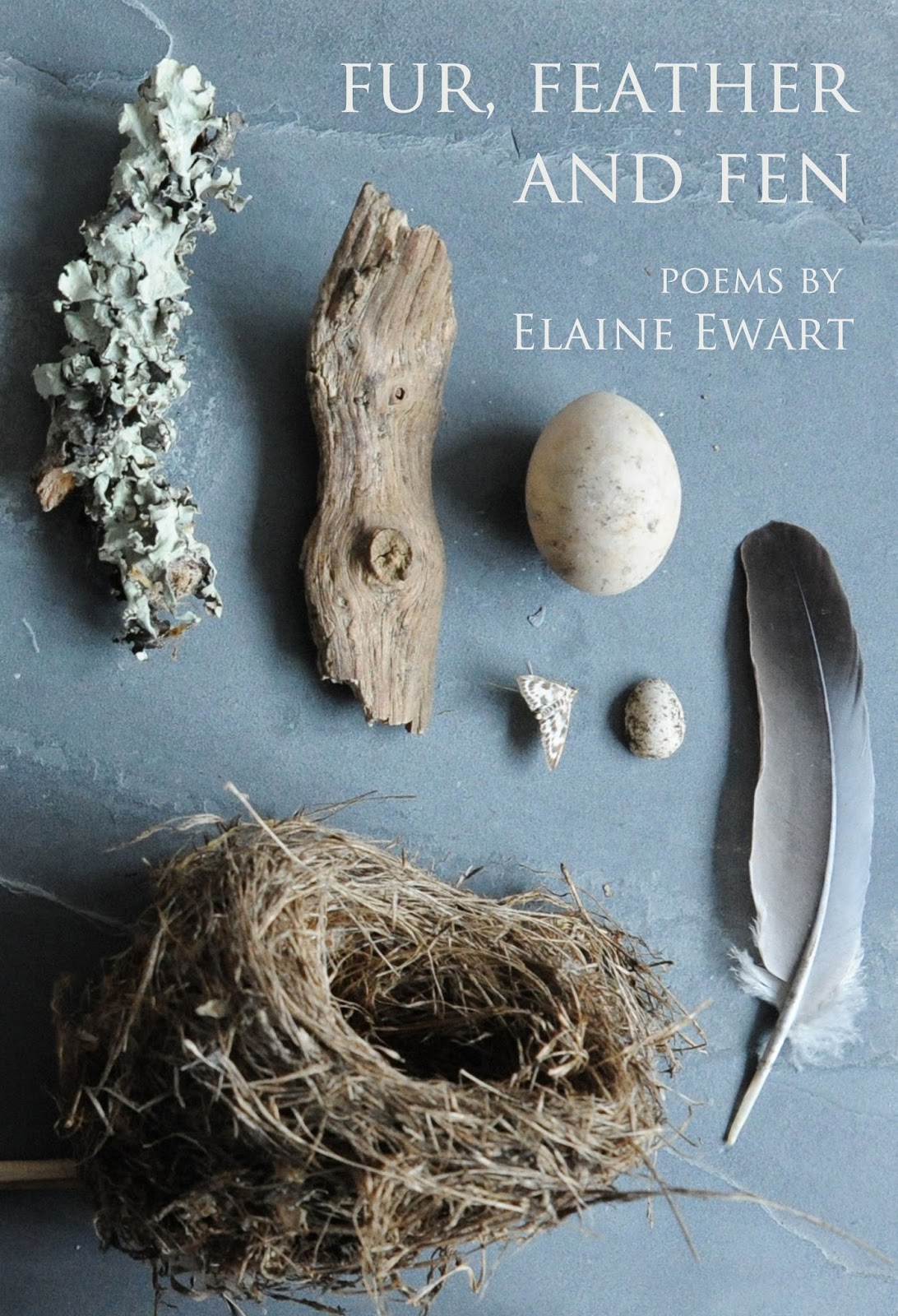

Fur, Feather and Fen by Elaine Ewart

-Reviewed by Bethany W Pope–

Elaine Ewart’s first pamphlet Fur, Feather and Fen (£3, FlightFeather Press) is primarily composed of poems that the author wrote while serving as the first Fenland Poet Laureate. Fittingly, the poems are largely focused on the natural world, inhabiting the perspectives of various birds and animals. The poems have a uniformly noble environmentalist slant and are peppered with Christian imagery.

The environmentalist theme is the greatest strength of this collection. Ewart knows the environment of the fenland intimately, and she occasionally conveys fragments and images of it to her readers. ‘The Drowned Lands’, the poem that won her the Fenland Laureateship, centres around a list of the avian inhabitants of the fen:

Across the field, banks hem in the horizon, sky hanging

Heavy over silver coin-puddles of squealing wigeon,

Fastidious-legged godwits; above them arch the flaunting lapwing

Through the mist, in soft-trumpeting cloud, butter-billed Bewicks

Raise mud-plated feet amongst the winter wheat.

For all of the multitudes she lists, details about the appearance and behaviour of the animals are surprisingly absent. We hear their names, occasionally their calls, but often cannot see them. What we do have are impressions: the mud-plated foot squelching among the wheat-stalks, the godwit’s fastidious legs. This is a more effective image if you know that a godwit is a large, long-beaked, round-bodied, brown-speckled migratory wading bird. It is not the responsibility of the poet to hand everything to the reader, but the poet must provide enough detail to allow the reader’s imagination to work.

Since many of these poems were ‘occasional’, written on request as a means of marking a significant date, it makes sense that there would be at least one holiday poem. ‘A Fenland Christmas’ presents a rather clammy nativity, setting the manger down, ‘close and clay-bound’ in the middle of an icy swamp:

A flock of white trumpets

Fanfare the dawn;

Lift their great wings up:

The baby is born.A blade on the ice;

A shot from the reeds;

In the arms of his mother,

Naked, he feeds.Hoar-frost reflecting

The light all around;

Love in a manger,

Winter sun-crowned.

It is reasonable to assume that since Ewart wrote this book during her laureateship she had a very specific audience in mind. To anyone unfamiliar with the landscape of the fen, setting the Nativity there creates a surreal conjunction of images that might leave readers who are unfamiliar with the environment feel as though they had entered an alien world, without reference or compass.

‘Selling Radman’s Grey’ is easily the most effective poem in the collection. Set in an early 20th century auction, it documents the melancholy that accompanied the switch from plough and horse-and-buggy to tractor and car. The reader is set down into the midst of the action; a horse stands on the auction block, ‘she shakes her dripping mane. / It parts each side of a mild dark eye.’ The auctioneer begins bidding, his voice in italics, ‘Who will start me with twenty pounds?’

The progressive farmer, Radman, is given more personality, through description and actions, than any other character in the book:

Radman, square as his pigs but not naïve,

Leans his bulk on the fence, chews his pipe;

Stares at the drizzle, at the rough-knuckled hands

Driving the last skittering sheep up a ramp.

This poem is genuinely affecting in places because the reader is made to inhabit the world of the auction, the dying world of the animal-powered farm. The reader is able to picture the horse as a living being, not a species checked off a list:

For thirteen years she pulled the pig-float,

Suffered fat-legged boys to be lifted to ride

Who now swagger new motors through town.

Fur, Feather and Fen is a book released too soon. The poet shows promise, she is certain of her theme and intimately knowledgeable about her subjects, but as yet that promise is undeveloped. Her second collection will fulfil the potential of her first.