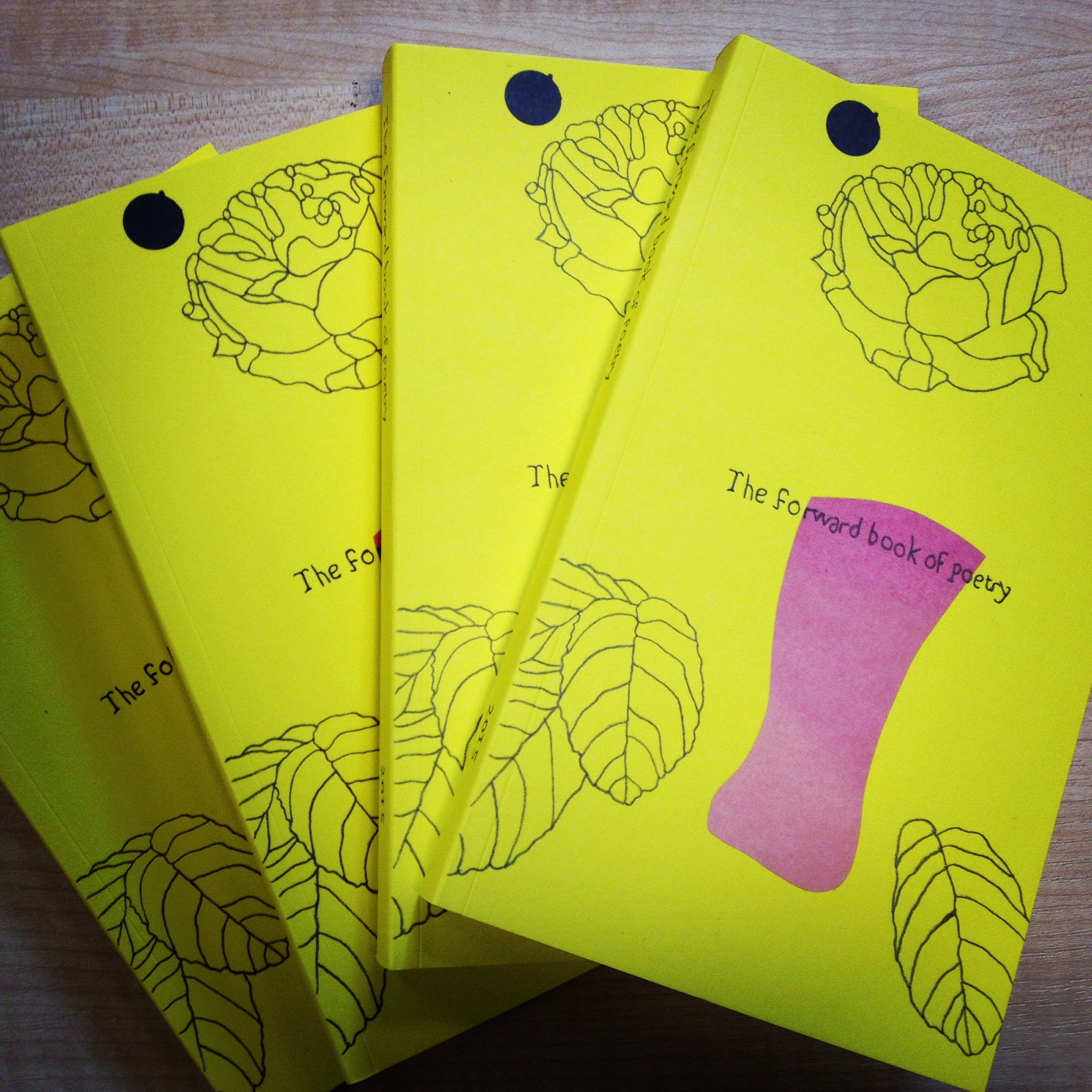

The Forward Book of Poetry 2014

-Reviewed by Rosie Breese–

Any anthology claiming, as The Forward Book of Poetry does, to provide readers with ‘a strong sense of the variety, vitality and wit present in poetry today’ has given itself a tall order to fill. Can a panel of five judges really distil a fair selection of what’s current, interesting and incisive? Can they rely on journals and presses to have carried out the first stage of this process? And can they adequately meet the needs of the ‘Common Reader’, who, as judge Jeremy Paxman points out in his introduction, could be anyone, anywhere? Add to this conundrum Paxman’s headline-grabbing suggestion that poets should answer to their readers through some kind of gruelling, presumably televised, ‘inquisition’, and this year’s Forward Prizes seem to have been well placed to stir up debate.

As well they should. Reading, to quote shortlister John Burnside, is a political act. And selecting a group of poems to be positioned as an overview of 2014’s best work and a guide to the current landscape of poetry for new and regular readers alike, raises age-old questions about the writing of poetry itself. What is new? What is interesting? What is worth reading, and why should we read it? Similar questions come up in the reviewing of anthologies. It’s nigh-impossible answer these, or to cover the sheer variety of content within the scope of one review – so please forgive me for taking a reader’s tour of poems that resonate with the themes picked out.

Round about the same time as taking on the Forward collection for review, I came across Steve Ely’s article for the Poetry School, in which he calls for ‘more poetry that goes beyond the passive, reactive and personal tendency that currently dominates and has the ambition and confidence to engage with public issues, to be about something’. The distinction between these two loose ‘types’ of poem, as identified by Ely, seemed particularly pertinent to a collection purporting to provide an overview of the best poetry in circulation. I was tempted to try and identify poems fitting these rather broad categories within the collection; to name the saints and sinners, as it were. However, the side-by-side pairing of Beatrice Garland and Kevin Powers’ poems immediately brought Ely’s generalisations into question:

You are sitting eating an orange,

not giving me any

and staring straight out to sea.The sand in front of me

is pocked with little craters,

every one a wild salt tear– Beatrice Garland, ‘Beach Holiday’

Here is where appreciation starts, the boy

in a dusty velour tracksuit almost getting shot.

When I say boy, I mean it. When I say almost

getting shot, I mean exactly that. For bringing

unexploded mortars right up to us

takes a special kind of courage I don’t have.– Kevin Powers, ‘Great Plain’

Despite the gulf in subject matter and with this, it might be argued, wider relevance, both of these are personal poems of ‘occasion, experience and impression’, as Ely puts it, engaging with huge themes – love, war – through the first-person lyric lens. So what is it about Powers’ poem that has brought me back to it again and again?

For me, it’s the language. Powers’ lines are unadorned and unpretentious, but they break unexpectedly, flip back and reassert themselves; they are self-aware as a mode of representation. The artistry is more than picture-perfect description. There’s an insistent urgency: ‘I mean it […] I mean exactly that’, redolent of Carolyn Forché’s poetry of witness, in particular ‘The General‘: ‘There is no other way to say this’.

From this experience, it seems that it is the engagement, the work inherent in reading linguistically inventive poetry, the mental leaps you take, that draw you into the world of a poem. A recent conversation with fellow reviewer Charles Whalley led to similar conclusions: there is a certain level of dependence, in poetry, on recognition by the reader. If that recognition comes too easily, it seems the poem is too close to our world. Little has been asked of us; we might mentally pat ourselves on the back for ‘getting’ the poem and go back to business as usual. But a poem that makes us question our viewpoints, shift our frames of reference in order to attain some twinge of recognition, has succeeded in drawing us into its world from outside. It speaks, to pinch a line from SJ Fowler’s commended poem ‘Trepidation’, ‘from the centre of a language’. We have been somewhere new.

For any reader, there will be plenty of poems in this year’s Forward collection that won’t bring surprises. Which ones these are, and whether this is a turn-off, will vary from reader to reader, so it’s hardly worth making a personal list here. There is no anthology that will please every reader with every poem.

However, for me, there were certain poets whose work stood out in its insistence on speaking its own language. Felix Dennis Prize shortlister Liz Berry’s poem ‘Nailmaking’ initially stopped me in my tracks because, being from the Midlands myself, her representation of the Black Country accent and dialect seemed curiously selective to me. But this confusion compelled me to read and re-read, and then to look up her readings on YouTube, and through this, to begin to feel something of the shining, real world of the poems under their layers of sepia and soot:

Marry a nailing fella and yo’ll be a pit oss

fer life, er sisters had told er,

but er’d gone to him anyway in er last white frock

and found a new black ommer

waiting fer er in ‘is nailshop

under a tablecloth veil.

Other poems whose ambition and inventiveness stood out a mile included Hannah Silva’s ‘A mo in a \_/ jar’, a half-story garbled in text-speak, itself a mode rapidly falling into obsolescence with the advent of predictive texting. In this way, the language doesn’t merely refer to ‘the ineffable’ – it enacts the layers of thought, of words, between speaker, reader and memory:

d tyms we weren’t blind

bac from d pub stumble

he spoke as f he’d raped me

n d tree’s branches brushd

agenst us 4 a mo.

Amongst the other commended poems, Daniel Boon’s ‘Crescendo’ certainly deserves a mention for its stupendous collisions between Dutch and English: ‘shards of glas / rend open the lucht and pan-tiles smash into vuur-dust ..’, whilst Andrea Brady’s ‘Export Zone’ dazzles and disorientates in equal measure: ‘the cash transfer from London / lite to salt lick has some chick as its / sole beneficiary. Would I like her / whipped or salted..’

David Harsent’s graphic elegy for martyred sixteenth-century poet Anne Askew also makes use of language from the world it speaks of, quoting from the notebooks of contemporaries as well as Anne herself:

Anne, you are nothing to me. Only that you knew best

how to unfasten your gown while they waited at the rack.

Only that she was hard prest

which I now can’t shake from my mind. Only that black

flux flowed from you, that they let you void and bleed.

There’s something uncomfortably voyeuristic about this fascination with macabre detail: Hard prest. Black flux. Why write this down and, if I find this so distasteful, why do I read it time after time? What does Anne mean to Harsent, or to me? What have we understood from the words he has appropriated? The focus here is turned as much on the reader as the subject.

For all this harping on about linguistic invention, an uncomplicated approach can also function as the bridge to a surprising world. Best Collection shortlister Colette Bryce’s poem ‘Derry’ begins without fanfare: ‘I was born between the Creggan and the Bogside / to the sounds of crowds and smashing glass’. ‘Creggan’ and ‘Bogside’ were just empty signifiers at the beginning of this poem. By the end, although my grasp of the geography of Derry is still fuzzy to say the least, I felt I had glimpsed something of the place and its turbulent history. Similarly, shortlister Hugo Williams’ ‘I knew the bride’ is all the more haunting for its short, simple lines. This poem is like a gutted house; its clean bones hint at the weight of the past, and a heart-wrenching story: ‘When you first crossed over / into that wintry place / you said you had a feeling even then.’

Returning to Burnside’s quote in the foreword, the stand-out poems of this collection demonstrate that poetry is indeed often ‘a defence of care over the language’, and that active reading may well encourage questioning of the self and others, and even of ‘the deceptive myths peddled by certain politicians and salespeople’. This may seem a grand assumption, but once something of the fallibility, the assumptions, the politics of a language is made evident, another viewpoint is unlocked; the door is open to change on some level, no matter how personal and small.

So I’m going to say something controversial here: Paxman’s comments about writers needing to answer to an inquisition of sorts were bang on. But let’s not take them too literally. Whilst a panel show featuring the man himself haranguing literary heavyweights on their appropriation and punctuation of human suffering would certainly be entertaining, the real ‘inquisition’ might be a more gradual, more personal questioning on the part of the thousands of readers, poetry lovers or otherwise, who will encounter these poems for the first time. Despite the limitations arguably inherent in publishing and prizegiving, the gift of this anthology is the gift of language, of inventiveness with language, of the immersive environments this language creates, and the issues these will raise for reader and writer. What is new, relevant, irritating, boring, is slippery to define. But to question is valuable in itself.

Wow, that’s an excellent review! Thanks to the reviewer for giving us so much in only a few lines…