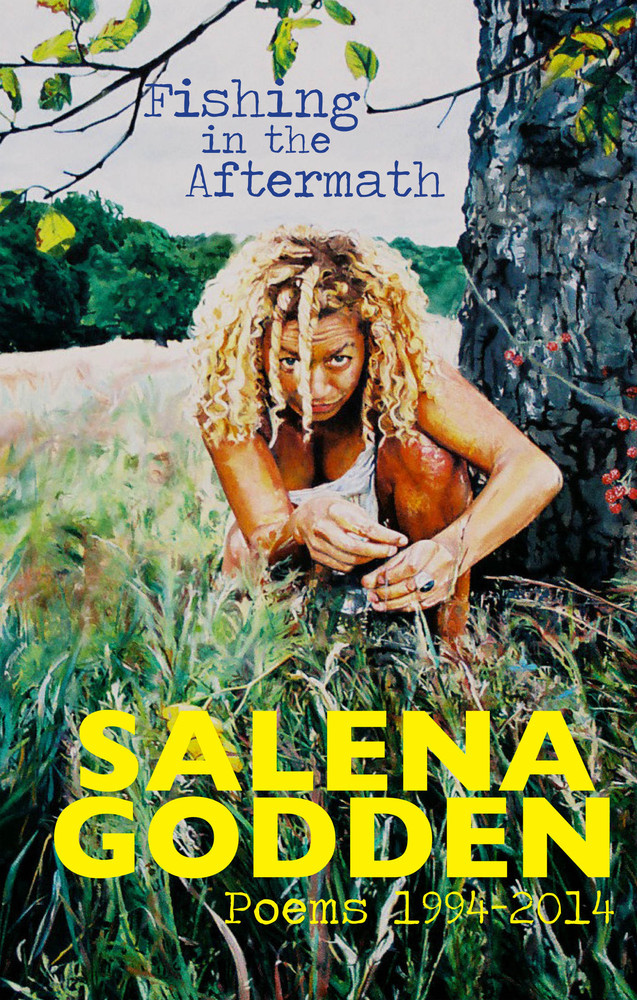

Fishing in the Aftermath, Poems 1994-2014 by Salena Godden

-Reviewed by Nicole Capo–

Salena Godden is a powerhouse.

Reading into her irrepressible energy, it’s no wonder that the British vixen of the underground performance poetry scene has a new collection spanning two decades of writing. Her work draws you in from the get-go, and finishing her book is like waking up from a days-long binge that leaves you raw and scrubbed clean, skin tingling from the connections forged by her words.

Fishing in the Aftermath, Poems 1994-2014 is a non-linear labyrinth exposing the vulnerability of a girl-turned-poet at the turn of the century, both in modern-day England and in post-9/11 New York City. It’s a melodic and unguarded coming-of-age story filled with moments of anger, sadness, friendship, loneliness, and red-hot passion. To say that Godden’s work is a reflection of a youth well spent in search of a higher meaning as an artist is an understatement — Her commitment to her work is refreshing in its honesty, and her decision to divulge the difficulties of the writers’ life rather than gild it in beautiful words as some do is immensely satisfying.

“Real poetry is dead poetry,” she proclaims in the anthemic “Tick No Box,” followed by the seemingly oxymoronic “carry on reading, carry on writing, as you were and as you are.” The need for recognition, understanding, and creating a sense of community among writers is the chief concern among many of her poems, and Godden’s melancholy optimism about writing as an art is ever-present throughout the years. “Words are marrow,” she tells an anonymous writer in “A Letter to a Young Poet,” which she closes with the words “Keep the ink wet and keep it burning.”

Godden — known on the stage as “Salena Saliva” — treads darker themes in many of her works, most notably the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in New York on September 11, 2001, when Godden found herself trapped in the chaos of the city. Drinking and casual sex become her mechanism for coping in many of the darker times of her life, and it’s that combination that seems to both hide and embellish her sadness, putting on a show for her readers that sticks in the blood as much as the alcohol does. “The Last Big Drinky,” in which Godden writes about herself in a week-long drinking binge from an outsider’s perspective, is an incredibly introspective piece about her loneliness, her addiction, her fight to elevate art as a profession, and her fear of allowing others to get too close.

“We share the fear,” writes Godden from the viewpoint of a friend taking care of her as she works the alcohol out of her system, “And holding my hand she is begging to be held convinced she will stop breathing. She says vodka and cock will kill her in the end and she feels as though she is rotting.”

Love is another main theme of Godden’s work, finding its way into most of her writing as an elusive force she can’t seem to master. “I Don’t Do Love” is at the centre of that struggle, and Godden’s fear of the feeling is only matched by her desire to throw herself into it headfirst:

I don’t do love, I said, and when I looked up and saw just who I had said it to love did me hard and tirelessly, until, there was no until, there was just love.

The range of Godden’s themes is impressive, covering issues like abortion, mortality, poverty, death, anxiety, and addiction in the same breath. She easily transitions from vulgar, lustful creature to loving, devoted friend and dozens of places in between. Take, for instance, the juxtaposition of her popular piece “Imagine if You had to Lick it!” in which she urges the reader to “IMAGINE IF YOU HAD TO LICK IT/that runny old dog shit,” with the sweet and heartbreaking sadness of “Milk Thistle and Juniper”:

Then we took the child with hair like the milkman

before she would show and so no one would know,

before waters broke streaming and screaming the dawn

with coat-hanger tangled and the salt to the slugs

that slid past the undergrowth, never to tell.

Then we took the child with hair like the milkman

out. Wrapped in the blanket and wet with soft bones dead.

Buried with feathers of crows, a poppy like red flows,

bloodied the muddied moss of the pebbled brook stream.

Though it’s clear that some of her work is meant to be passionately performed onstage and not hidden away in a written collection, the pure, unfettered honesty of her writing is its salvation. “Fishing in the Aftermath” is a book definitely worth a second and third read. It is, as she states in “A Tribute to Cheryl B.,” “a heart that spilled and splashed/and silenced a room.”