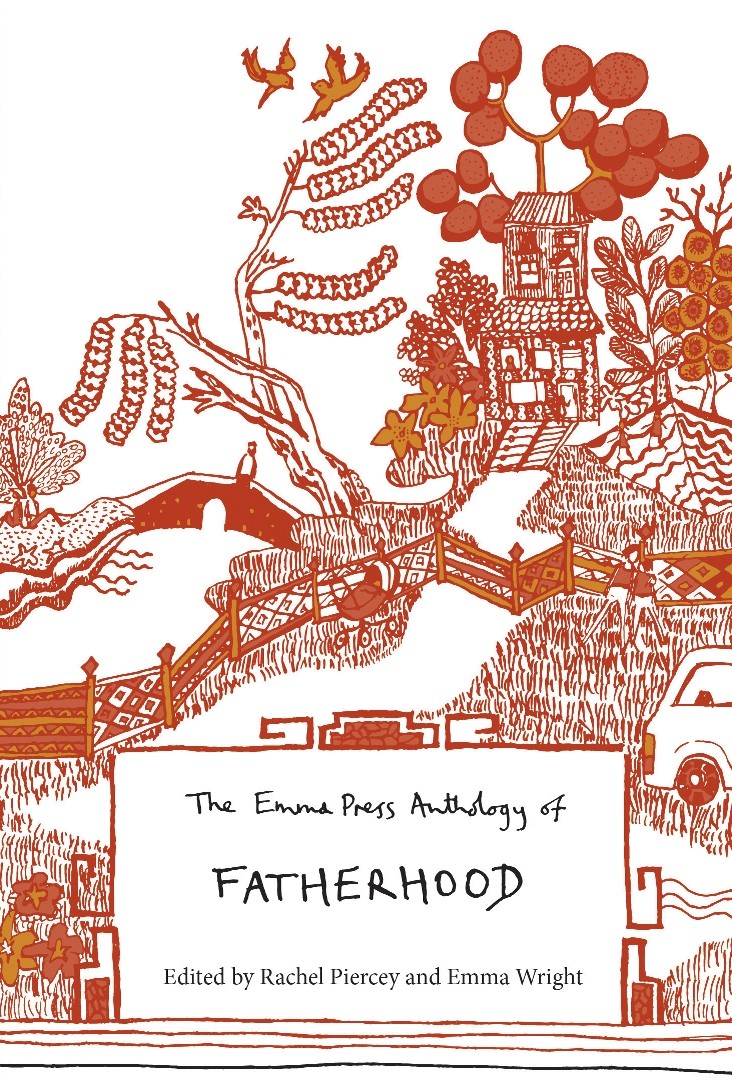

The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood and The Emma Press Anthology of Fatherhood

-Reviewed by Angela Topping–

Parenthood has been an enduring subject throughout the history of poetry. It is good to see this tradition continuing; indeed there has been a buzz of recent activity surrounding it, including Mother’s Milk Books anthology Musings on Mothering (2012) and Carolyn Jess Cooke’s ‘Writing Motherhood’ blog for Mslexia. The Emma Press books are companion volumes with matching covers using the willow pattern as a motif. They are both edited by Rachel Piercy and Emma Wright but despite that, I felt the anthologies were very different.

I was expecting the anthology to be about the state of motherhood but I found the opening section very disquieting. It turns on the theme of mothers with mental health problems. This section is a very odd beginning to such a book. It would have been better placed at the end, along with the outcome of ageing and the shift in responsibility. The first poem in the book is outside this section, but would fit into it so I was puzzled by its solo positioning after the introduction. Being a mother is not a requirement for mental illness, though it may be a factor. Most of the mothers in this section are older, becoming like children to their daughters, like in Deborah Alma’s poem, ‘My Mother Moves into Adolescence’. This is a sad, vivid poem, which shows a selfish mother for whom the patient daughter can do nothing right. I enjoyed its question and answer structure. My favourite poem in this section is Jacqueline Saphra’s fabulous list poem, ‘My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury’, which is a wonderful period piece:

Beehive proppers backcomb teasers

Pinpoint pluck of fearful tweezers

Leak of mouthwash morbid flavour

Dutch-cap dusted snap-shut cover

One can easily imagine the round-eyed daughter watching her mother at her toilette, and learning feminine tricks from her. This poem does not seem to me to fit into this section at all, but it is one of the most vital and touching poems in the book. It celebrates the mother’s femininity and sexuality, and shows that being a mother does not take away from a woman’s role as a sexual partner or a person. I enjoy its clever half rhymes and sensual sounds.

The second part is closer to what I was expecting, as it focuses on that stage of motherhood where a small baby is involved. This would have made a more logical opening section. There are poems of loss balanced against joyful poems here, which reflects a range of experience. ‘Where the baby isn’t’ by Hilary Gilmore comes at the sorrow of losing a baby from an unusual angle and is moving because of its lack of self pity and the continual absence of the baby from all the diurnal ordinariness:

The weeks, the year ahead resound with the

Nothing, where the baby isn’t, and the

Whole wide shape of world is a mirror

Reflecting where the baby isn’t.

The joyous carrying of a baby is celebrated in this marvellous poem by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi, ‘I have a comfort house inside my body’, which reminds me a little of that wonderful poem by May Swenson, ‘Question’, as well as Pablo Neruda’s odes. The imagery is lush, it is a list poem of great expansiveness: I’d love to quote the whole thing, but I lack space for it. Here is just one line: ‘I never knew that I had a planet inside my body’. She has a pamphlet out with Emma Press and I really want it. One function of an anthology is to find poets one hasn’t read before, to add to the treasure house of personal favourites. Box ticked.

The third part seems to continue this focus and add to it the process of birth, that transformative process which changes how one thinks and feels forever, like the membership of a secret club. Once a woman has passed through that experience, everything is changed forever. I loved Carole Bromley’s ‘DIY’ which expresses just what I, and many other mums I’ve spoken to, felt about housework when there was a small baby around. Prioritise: ‘Sit down, pick up your guitar / and sing to her’, and that is before the child is even born. Stephanie Arsoska’s poem ‘Cocoon’, Clare Pollard’s ‘Emmanuel’ and Kathryn Simmonds ‘The New Mothers’ are all stunning poems, in fact I enjoyed every poem in this section.

Part four tackles the state of motherhood as the children grow up, pull free, turn teenage and difficult. Some of these poems are uncomfortable, some edgy, some sad. Being a mother of girls myself, I particularly liked the daughter ones. After this section, there is a blank page, I am not sure why, then the book ends with a Liz Berry poem, ‘The Night You Were Born’ in which a pregnant speaker wishes she could have seen her husband being born. It’s a fine poem but it seems an odd ending for such an anthology.

The editors have set out, as far as I can see, to create an edgy anthology to counteract any squidgy feel-good notions about what motherhood is, but sometimes the selection lacks heart, feels too abstract or as if there was too much of an agenda in what was being looked for. I am thankful that there are many poems in which heart and head are balanced, where emotions have a place, because whether it’s hard or easy, motherhood is an emotional and visceral place. It would have been good to see more poems tackling the death of one’s mother, which is a time when their role in our lives is re-evaluated. The elegy poem is completely omitted from the anthology.

The Fatherhood anthology is more as I expected it to be. It does what it says on the tin, in distilling what fatherhood means. It is a more cohesive selection. Emma Wright says in her introduction that: ‘we expected some responses to focus on the pressures of modern fatherhood… instead poets seemed preoccupied with their own fathers’. Perhaps this is why the selection of this book is ultimately more appealing. There is no explicit division into parts, just a page with an illustration at intervals. Poems by men about their experiences of fatherhood are interspersed with poems about fathers and there are several elegies, like Sara Hirsch’s ‘Tonight Matthew’ which is four page poem about reclaiming her father, who died when she was 12. The rhyme gives the poem its impetus, as does the developed metaphor of a train journey. I love Martin Malone’s villanelle ‘Digitalis’ which is about his father’s mellowing when he became ill:

Dad was Dylan, McCartney, Jack Kerouac

in that last fond Summer of Love

between his first and third heart attack

when an unknown younger man came back.

Hugh Dunkerley’s poem ‘Coming Home’ works by exploiting the contrasts between the harsh world outside and the tender conveying home of a premature baby. The fact that the baby can’t settle, missing the incubator, is honestly faced and ultimately moving. The father’s determination to protect the fragile infant is expressed subtly, driving home ‘as if the slightest bump could shatter you’. I wasn’t sure why another poem of his, about the same child’s birth, was placed in a different part of the book. Rachel Piercey’s poem about her father, ‘The Words’ with all its particularity and concrete imagery, is similar to her poem about her mother in the partner anthology. On the whole the poems in the Fatherhood selection seemed more physical, more tangible, more concrete, less abstract. Alan Buckley’s ‘Handshake’ and Oliver Comins ‘Brown Leather Gloves’, though separated in the book, speak to each other and would have gained from being juxtaposed. Both are moving and full of particularities, details which bring their fathers into the reader’s ken. Buckley concludes his poem with this understated image:

My right hand

drops, meets his

in a firm grasp.

My left hand

hovers in mid-air,

not knowing where

it should land.

Comins’ poem is a meditation on his father’s ‘brown leather gloves’, which he is wearing on a cold morning. The gloves have a strong presence in the poem, bringing in his father symbolically:

Who’s holding whose hands now?

Inside the fingers there’s

more of him than there is of me –

all those years of rubbed skin and sweat.

These are moving poems which have a perfect balance of craft and heart. I would have liked to have seen more poems like this in the Motherhood anthology. Emma Press is doing some very interesting things and should be supported. The books are neat in size and beautifully presented.