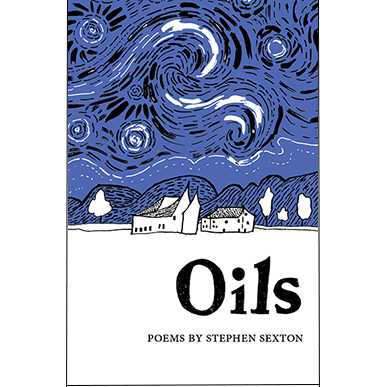

Oils by Stephen Sexton

– Reviewed by Stephen Payne –

In Stephen Sexton’s Oils, full of imaginative, lyrical, layered poems, ‘Long Reach’ is the most layered of all: “after Anne Sexton, after ‘The Starry Night’, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889”.Some readers will know Anne Sexton’s poem ‘The Starry Night’, and many will know the Van Gogh painting about which she writes “This is how I want to die”. I presume Don McLean knew Anne Sexton’s poem too — it gave him that doubling of “starry” that it’s hard to read without hearing his melody.

Stephen Sexton begins with Anne Sexton’s first line “The town does not exist”, and continues with a strange explanation:

The town does not exist because you live

there now. The black, septic tree — the drowned woman

you wanted — does not exist in its almost-reach

into the evening. Land in the patchwork town

and forget that vortex’s crook-armed hold

above the steeple, tavern, grocer, which don’t exist.

Perhaps this suggests that a work of art loses its extension to reality if studied or worked on or lived with sufficiently closely. The “you” is Anne, to whom the poem is addressed (unless it’s Vincent Van Gogh, and the addressee of the poem slips during its progress; I’m not completely sure).

So, a poem about a poem about a painting, addressed to the first poet, a namesake of the current poet (surely no accident). ‘Long Reach’ explores mimicry and inspiration, the ongoing life of artworks. It seems to emerge from an immersion in Anne Sexton’s poem, and in Van Gogh’s letters – which Anne quotes from in her epigraph and Stephen quotes too – as well as tracking Anne Sexton’s online presence. The poem asks about her own process (“Did you mention Vincent and reach for his letters?”) and ponders the nature of representations: “Do letters exist, / or only the short-range burst of live / rumour from parlour to parlour across town”? It also questions whether digital technologies change the possibilities of art, as well as its reach.

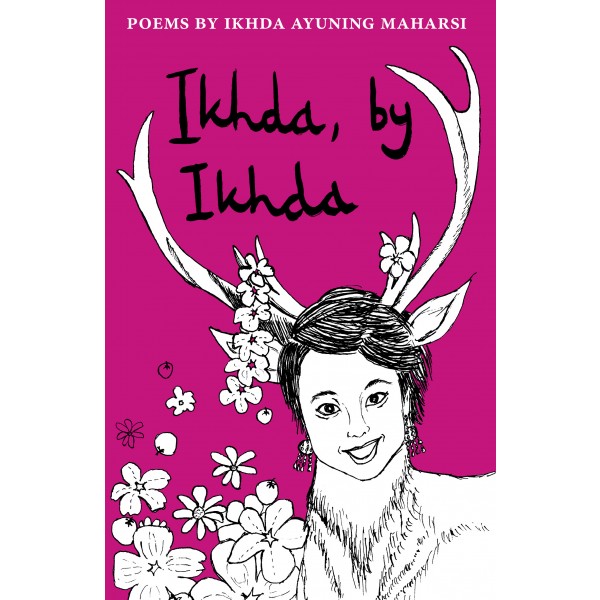

It’s a rich and unusual poem, and I enjoyed puzzling my way through, following my own first-name namesake to Anne Sexton’s Facebook page and the newspaper stories of her death, retracing, I presume, some of Stephen Sexton’s own steps of discovery. No surprise that such an involving poem should fire editor Emma Wright’s imagination and lead to her lovely cover design — a blue, black and white sketched version of The Starry Night.

‘Long Reach’ is not the only ekphrastic poem in Oils; there is a sequence of three poems about paintings of Orpheus (re-representations again), ‘The Deaths of Orpheus’. Here is the first stanza of “A Flattering Look”, after a painting by Gustave Moreau, Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus:

Look when my head washed up on the shore

I was singing through the salt — they seem sure,

and it’s mostly true — but by then I was mostly salt,

I meaning head and what remained of my throat.

I don’t know why that big space after ‘Look’, where a comma might have served, and I don’t understand why the poem is presented right-justified, which makes reading awkward. The poem gives Orpheus a rather world-weary, matter-of fact voice which focuses on sensual details in the scene (as I suppose a disembodied head might): “She wore lilacs, mint, fennel in a bunch at her solar plexus / and I smelt the brightness of lemons from under me”. It ends with the head bemoaning its imminent burial, a kind of second death.

Turning to John William Waterhouse and Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus, we meet another very sensual poem, this time arranged in quatrains and suitably nineteenth-century in tone. It’s a single 24-line sentence, impressively easy to parse, alluding to the life and death of Orpheus in a chain of jealousies: “the mountaintops envy the scum of the sky”; a girl’s hand is “envied by waterlilies and peonies”; the moon resents the sunlight; and finally, Orpheus, half-drowned and himself (like those who killed him because they couldn’t hear his music) “jealous, / O insects, jealous is what death is”.

In the third Orpheus poem, ‘Red’ (after Antonio Vega, The Death of Orpheus) the register shifts to something more contemporary, though we still have Orpheus talking about death, and what he’d been unable to imagine about it in advance, bringing me back, perhaps fancifully, to Anne Sexton’s ‘The Starry Night’.

These poems from paintings give Oils its neat title, along with a very different poem, ‘Elegy for Oive Oyl’, spoken by a rueful and lyrical Popeye. (I’m willing to bet this is the first collection to present poems in the voices of both Orpheus and Popeye). It’s a lively, surprising poem, awarded third prize in the 2014 Poetry London competition. I must admit I find it hard to feel Popeye’s pain, but then I can’t remember the cartoon very well, and somehow wasn’t inclined to chase these references online. I did wonder whether “Your body gestured commensurate with // mastheads asway blindingly against the sun” might not be more in Sexton’s language than Popeye’s, who had “I bears this in mind” as a verbal tic.

I’ve focused this review on these poems because the title and cover suggest that Sexton himself sees them as central and representative. They are indeed representative of the bulk of the pamphlet in their density and intensity; many of the poems (e.g. ‘On Betrayal’, ‘The Death of Horses’) have a rather complicated surface, at least for me, and give up their significance gradually if at all, over many readings. Nevertheless, I am always convinced there is something interesting going on, some depth of thought, some originality of observation and expression.

Formally, the poems are more conventional, free verse, with just the occasional presentational quirk, such as those mentioned above and a line in ‘Young Bean Farmer’ that reads right to left and down a staircase of words.

A few poems (there are sixteen in total) seem more direct in their address and more transparent in their concerns. I wonder, in fact, if these aren’t the strongest poems, because even when being less overtly intellectual — love poems, a poem about a high-end HiFi, about a school English lesson watching a film of Romeo and Juliet — Sexton finds lyrical touches that are new and winning.

For example, there’s a beautiful sonnet-length love poem called ‘Subimago’ (a stage in the development of a Mayfly; I looked it up) which opens jokily with “I have been well prepared for small endings. / At eight years old, my first poem killed a mayfly” and progresses to play out a romantic end-game, the walk through the city to the anticipated final conversation:

Telling the long story short takes longer than the long story.

Study each red man with hands by his sides at each crossing.

I will your house (I’ve never seen) to pull further away.

I will the frozen avenues longer.

These lovely lines show one of Sexton’s best tricks. The language is slightly elevated, and the emotional punch hits dead centre.

I might add that the overall production of this pamphlet is very stylish and high-quality. Emma Press have done Stephen Sexton’s intriguing poems proud.