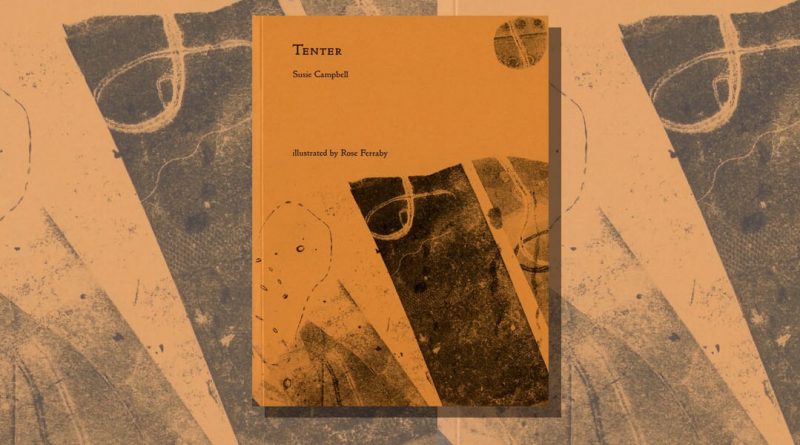

Tenter by Susie Campbell, illustrated by Rose Ferraby

-Reviewed by Stephen Payne-

A tenter is a person who stretches cloth, or the framework on which the fabric is held. If this book is the framework for these taut poems, then I might begin by observing that it is a beautiful thing –Guillemot Press have done the poet proud, with a handsome dark yellow cover decorated with one of Rose Ferraby’s organic, abstract, intriguing monoprints. More of these prints appear throughout the 50ish pages, (usually on pages of their own) alongside pages of poetry, all “printed on Mohawk superfine papers and section sewn” according to the Guillemot website. I can confirm the feel is substantial and very high-quality.

The poetry is laid out as prose paragraphs. It is ambitious and layered, and uses strategies of fragmentation, disjunction and quotation — clauses are easy to parse, their order is more challenging. The ideal reviewer would be more comfortable with Latin than I am. (Latin phrases are interjected or quoted in some of the poems, without translation). They might also be already better informed about the Battle of Hastings, The Bayeux Tapestry and the D-Day landings. I have mugged up as I go, because the poetry, and the design of the book, encourage thoughtful reading. The five poems bring together these historic elements with the contemporary refugee crisis to raise questions about commemoration and memory, international conflict and individual autobiography.

The first poem ‘Memoration’ is as a sequence of nine dictionary entries for cognates, a single entry to a page. Here is the very first:

Māmor, Old English (deep thought, deep inwards) as a

tree gives way, or the side of a hill from beneath. To leave

this behind, each of us going back far enough

As you can see, it’s like a dictionary entry, but different. The definition is in parentheses, as if this were only worth mentioning in passing between the language-of-origin and some associative, autobiographical, narrative sketch associated with the word’s meaning. Perhaps the implication is that personal meanings go beyond the public facts and take priority. Also, that these personal meanings are fragmentary, even if the fragments accumulate to something akin to story. The story, in the case of ‘Memoration’ begins with a family home being left, moves on to war in the north of France, and ends with a contemporary tragedy of smuggled refugees.

The second poem, ‘Et Aelfgyva’ is (the Notes tell us) named for one of the few women depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry. It tells the story of the Tapestry’s creation, in the voice of one of the women embroiderers. The language of the prose is readable despite its compression, even if the reader skips or guesses the Latin phrases (quotes from the Tapestry) of which there are two or three in most of the 12 paragraphs of the poem. One unusual typographic gesture is that the sentences end with full stops, but don’t begin with capital letters, unless they are in Latin.

‘Wound’ tells of a British soldier’s experiences on the battle grounds of France during WW2. The text includes extracts from the medical record of the soldier (the poet’s grandfather), and interleaves lines from a children’s rhyme making this poem visceral and hard-hitting:

left on a slag heap an abandoned slaughter-house

perrie merrie dixie domine

these memories start in the scapula a flexing and a stirring

in his clavicles and deepening down into the breastbone

‘Hush’ is the shortest poem in the set, taking up just a single page. It’s about revisiting a battle field. It’s in the second person, and I think the ‘you’ is the soldier, although it could be the poet, visiting, as it were, on behalf of a relative. The struggle of writing about this material becomes a theme for the poem, an extra layer of its meaning: “You expect to come here to honour the dead. An open field looks like battlefield words: gone, absent, missing.”

The final poem, ‘Our D-day’ is disquieting in the way it describes the war grounds as a tourist destination, borrowing statements from real brochures, and blends this material with recent news stories about the Calais refugee camp, which directly and movingly insist that the horror of war continues:

then there are no trees no help comes about

300 children are turned away and many are standing under

a nearby bridge not knowing what to do there are no

trees just a wire fence