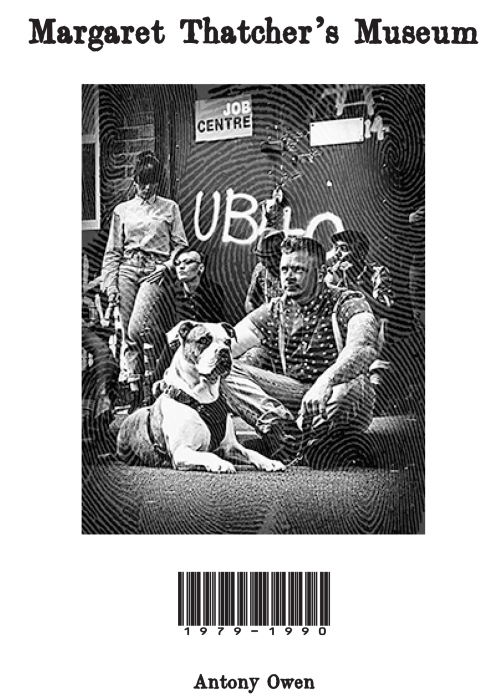

Margaret Thatcher’s Museum by Antony Owen

– Reviewed by Emma Lee –

Margaret Thatcher’s Museum recounts growing up in the English Midlands during Margaret Thatcher’s time as Prime Minister (1979 – 1990), when Coventry’s main employers – chiefly the car industry – were shutting down, unemployment was on the rise and the spectre of the Cold War loomed. In “The Other Iron Lady”, this heritage is explored:

I was the son of a woman who spelt big words wrong,

yet did little things right; who knew the dialect of love,

who was the great unsaid, till it had to be said.I was the son of a man who drank beer, but displayed wine

in spray oak cabinets, so people thought us posh,

till Ma said shit and sorry and take me as you find me.I was the son of an unremarkable woman,

who wanted to be clever but a Mother more,

yeah; I was the son of a song never heard.

Antony Owen shows how working class aspirations were dampened and people kept in their place: the mother who wanted to learn but chose children, the father, owner of un-drunk bottles of wine, trying to raise his reputation on foundations as shaky as his oak-veneered chipboard cabinets. The son grows up to recognise that his mother’s economic worth is judged worthless, and that his roots lie with a class that won’t be heard.

The strength in these poems is their lack of ranting or of self-pity. They acknowledge the difficulties Thatcher’s government policies created, without preaching and without demanding that the reader takes sides. “Cold War Photographs” looks at family photographs stored in the loft:

We are all here curled in colour,

barely held together by hair bobbles,

which Mum only wore on chip-pan Fridays

before the ‘must-have’ perm of nineteen eighty summat.We are here in this moth-ping light,

that money shot of a shit beach in Malta,

us five in a red-ear sun going down behind us,

where whelks clung to rocks to never leave them.

Whilst the children have grown up, “life changed us to give life; / yet some of us are still there in the old one.” It says something about the familiarity of their relationship that the poet can date photos by his mother’s hairstyles. The father’s aspirations to a foreign holiday, probably picked to impress the neighbours, rather than with the family at the front of his mind, is mocked by the “shit beach” and red-eared image of the setting sun.

However, the poems here don’t just cling to the past. “Birmingham Library is Closed” compares and contrasts attitudes which led to library closures in the UK 2012 with post-Hiroshima rebuilding in Japan (complete poem):

Made from the tree of fire,

book spines melted, yet within eight months

Hiroshima library re-opened; in wheelbarrows that

carried bones and tatami mats of skin,

to men with covered mouths.

In Birmingham library today,

the mouth of literature is closed like a Nagasaki clam,

and I drop an F Bomb to Joe,

saying unread books are a little like sparrows,

crammed in quiet cages, inside golden Bangkok palaces,

where poor people yell for money to release them. This is it;

the money is given, but the bird forgot to sing and flies back into the captors hand.

Meanwhile in Hiroshima,

blossoms burst

books open

close.

In Hiroshima the blossom will become fruit; in Birmingham only those with money will read, consigning those with no economic worth to never blossoming. There are a couple of possessive apostrophes missing, but the meaning is clear, and their absence fits the old fashioned courier font and presentation reminiscent of printed and stapled political pamphlets, complete with a bar code number 1979 – 1990.

Overall, Margaret Thatcher’s Museum compassionately curates, recording rather than ranting its anger, reminding readers that those cast on the unemployment scrap-heap were humans, not statistics. I would much rather my taxes were used to curate and enable publication of poems like these than the proposed museum to Thatcher herself.