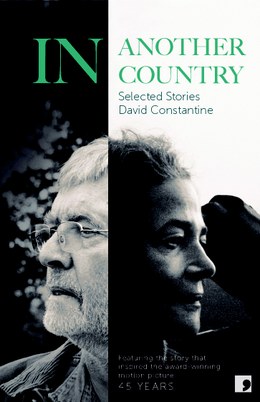

In Another Country: Selected Stories by David Constantine

– Reviewed by Frank Lawton –

These are landscapes of liquid and light, populated by the isolated, the lonely, the absent. Reading David Constantine’s In Another Country: Selected Stories we repeatedly encounter characters on the move, often escaping something – their past, the death of a loved one, their future – or trying to find what is only half-lost, trying to locate that which lurks on the border between the transient and intransient. This is a world of strange, abandoned or forgotten places: lone houses lost under motorways or dwarfed by dams, metaphysical shielings, spartan chapels hidden by the road and cradled by the sea, cursing wells and abandoned. This is a world of the margins.

While some Selected Stories can read like disjointed ‘best of’s’, In Another Country feels like a unified work. There are rarely vertiginous geographical or spatial shifts from story to story. Instead, each story appears as a scene from a single imaginative world. While each tale inhabits its own independent space, these stories reach out to one another, working to build up a tapestry of atmospheric relations. In doing so, paradoxically, an imaginative community is created which subtly locates the lonely and the isolated in the same drifting world. The home ‘under the viaduct’ in ‘Under the Dam’ is conveyed as an almost exact replica of the ‘house under the railway line’ in the syntactically strained ‘Trains’, possibly the weakest story of the collection. In ‘The Necessary Strength’, a portrait of a couple breaking apart under the weight of a wife’s increasing physical disability, the husband Max escapes ‘up the aluminium ladder out of the living room into the loft above it, where he worked’. Max’s private work comprises of detailed drawings of ‘bones or bone-like things’, as if, in escaping to the loft he escapes the reality of his wife’s suffering and recovers the past, anatomising the mechanics of Judith’s declining health, fascinated by the source of their relationship’s fracturing.

This recalls the ladder in ‘In Another Country’, which is ‘permanently down, encumbering the way into the little living room’. As in ‘The Necessary Strength’, the loft is a sequestered space. When Mr. Mercer receives news that the body of a lover who died in an Alpine accident when they were hiking together has finally been released by the ice, over half a century later, he buries himself in the loft, a place ‘bitter cold and draughty, where they stored the past’. Here, as Mr. Mercer rummages through his stored memories, the past and its preserved grief is quite literally opened up. In both stories that ladder becomes an image of escape and of pain: Judith, Max’s wife, ‘now never went up there, the ladder hurt her, it was too steep, as he must have known it would be’. The ladder serves to remind Judith of what has been lost. She is taunted by the past, much as Mrs. Mercer is isolated by it. Where Judith can’t physically follow, Mrs. Mercer cannot (or will not) emotionally follow.

The emphasis upon frozen relationships is mirrored by characters who freeze, such as Mr. Silverman of ‘The Loss’, whose soul suddenly departs from him while he gives a speech, or are already frozen, such as Arthur Barlow, who, while sitting alone attempting to write poetry in the suit he wears to funerals, feels a ‘loneliness, hopelessness, deep deep sadness’ which ‘possessed him utterly, froze him, the pen still in his hand, and he seemed to be seeing…not just through tears but through ice’.

Water (in all its forms) is David Constantine’s natural imaginative habitat, and it runs through this collection like a river upon whose banks many of these stories are built. In Constantine’s hands water both is and is not itself. While it always has a literal role to play, it is frequently metaphorically transformed into a receptacle for memory, an image of what is both transient and permanent, something that shifts yet stays the same. It is, evidently, a fluid metaphor. However, when water is turned to ice the emphasis hardens to something darker: ice is a Dantean punishment in ‘The Loss’, and a description of the particular type of loneliness which the protagonists in ‘The Strength to Help’, ‘The Necessary Strength’ and the wonderful ‘Goat’. It is ‘In Another Country’, though, which manages to combine the metaphorical aspects of water with the harder, painful edge of ice most successfully. Here the ice is not just a punishment – a reminder of a painful past – but an almost literal vehicle for memory in the form of a glacier. The image of the melting ice allows Constantine’s evident ecological concerns to express more than just a depersonalised and well-rehearsed narrative of global change: here ‘this global warming’ becomes a metaphor for the individual process of forgetting, as the ice melts and flushes out the suspended body of a long-dead former lover, whose perfectly preserved form will finally begin to decompose, and with it allow Mr. Mercer the chance of closure as he sets out to the Alps to visit the past for one last time. Thus, the global and the individual become two tributaries of the same stream.

As we have seen, characters in Constantine’s world often seem to ascend in order to retreat into the past. The intersection of these horizontal and vertical vectors provides a liminal space in which a number of Constantine’s characters are often at their most comfortable. This is the case with Lou in ‘The Cave’, who ‘between the two simple planes of earth and sky…entered a happiness she imagined most people had enjoyed, and many could still go back to, in childhood’. The darker intimation that Lou herself cannot look upon a happy childhood is never directly explored, but rather left to simmer away under the surface, only bubbling up metaphorically in the form of the water falling in the cave, that ‘long-after sound, carrying in it the remembered horror of the making’. Constantine can be a deeply lyrical writer of nature, reading a gentle, fresh beauty into well-worn images: ‘quietly they moved through the apple light plucking fruit that was shining pearl and shades of red and gold and underwater green.’ But the ‘horror of the making’, and all that the roar of the water in the cave gestures towards, serves to remind us that Constantine’s lyricism is not blind to the darker sides of nature.

Such darkness is wed to a psychological darkness in the excellent ‘Wishing Well’, which opens with another of Constantine’s key materials from which he builds his fictional worlds: ‘“The light, god-given, the light / When that comes / Brightness is on us, brightness / and life is lovely.” And so it was: light coming, alighting, playing all over, but over the two of them in particular, like tongues.’ It is no surprise that light plays such an insistent role in Constantine’s setting of atmosphere and descriptions of nature: like water, it is a flexible building material, both a presence and a physical absence, both revelatory and blinding. However, Constantine’s deployment of it sometimes lacks a light touch, with an increasingly predictable tendency to constellate descriptions of water and light, so that towards the end of the collection when a description of water appears you can be sure that a sentence on the play of the light will follow fast on its heels (I counted this phenomenon in 13 of the 17 stories).

Nevertheless, this criticism is slight when held up against the many triumphs of this volume, central among them being the two stand-out stories ‘Tea at the Midland’ and ‘The Shieling’. ‘Tea at the Midland’ won the 2010 BBC National Short Story Award (while the collection to which the story lends its name won the prestigious 2013 Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award). The five-page story is a work of graceful economy and power, and displays the very best of Constantine. In ‘The Shieling’ a couple journey towards a shieling constructed in the mind. The prose is dream-like and incantatory, in which there lingers something undefined and unsettling. The position of the interlocutor and listener (and by extension the reader) is never made clear, nor is their relationship to this private thought-place which is being revealed. What is the relationship of the speaker to the narrative ‘I’, or indeed the ‘we’ which pops up later in the story? Where is this revelation taking place, and, perhaps more importantly, why is this thought-place being revealed? When the shieling collapses into ruin and is seen once more the speaker ‘was inconsolable. Still am in fact.’ The lack of a comma after ‘am’ draws our attention to how what might appear a form of closure is, in fact, nothing but. Without a comma the colloquial is subtly resisted and emphasis is placed on the phrase as a whole: having had a mentally tactile world constructed from the imagination, what is ‘in fact’ can actually be less ‘real’ than what is not fact but fiction; the interplay between thought and physical reality, between fact and fiction is blurred, and perhaps shown to be an unhelpful, even unnecessary, binary. It is in this in-between, blurred space, that Constantine’s most successful characters exist.