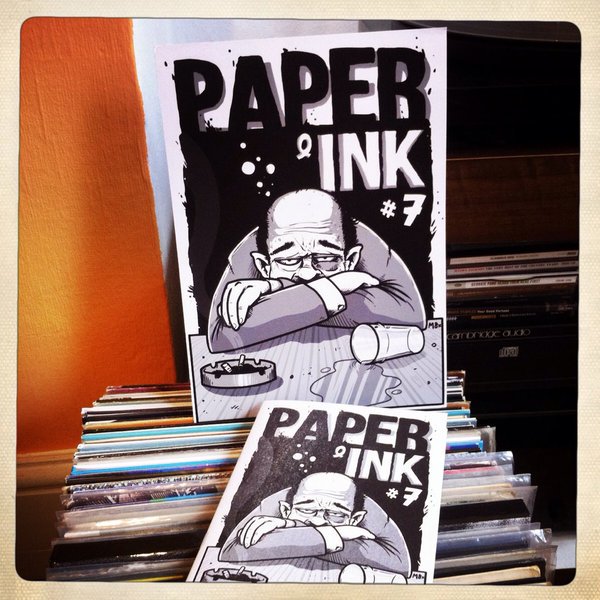

Paper & Ink #7: Hangovers

– Reviewed by Jenna Clake –

The theme for Paper & Ink’s seventh issue is ‘hangovers’, which (perhaps inevitably) results in a dark, unrelenting read. Not that editor Martin Appleby is unaware of this; he concedes: ‘After reading this issue you will probably feel like you have been for a night on the booze with Charles Bukowski.’

Nick Ryle Wright’s ‘The Lockout’, Joseph Ridgwell’s ‘A Two Day Old Pony’ and Andrew Climance’s ‘Fucked by the Big Fear’ feature men trapped in repetitive, self-destructive behaviours. In the former, the protagonist, Sampson, notes that his daughter:

probably knows everything; how he rode the bus to that pokey dive a couple of towns away; how he attempted to endear himself to the new crowd of people to whom he wasn’t yet financially or morally indebted; how he woke up near the bus station minus his keys, his wallet, his phone and his left trainer.

There are moments of wry humour to lighten the tone, such as Sampson’s note to his liver whilst drinking from a garden hose: ‘Dear Liver, Thought you might appreciate this. Sorry about last night. It won’t happen again (fingers crossed!) Love, Sampson x.’ However, moments later, he is considering how to get his next drink ‘to get his circulation going’, and the miserable cycle begins again.

‘A Two Day Old Pony’ is a more visceral account of a hangover. The narrator wakes after ‘an all night drinking session’ immediately determined to find somewhere to have another drink, simultaneously preoccupied with his need to find somewhere to go to the bathroom. The narrator’s casual misogyny (‘Tilda was a looker, and the type of girl who radiates sexuality, or in other words, might just be up for it’) coupled with his crude descriptions of his bowel movements, makes him severely unlikeable, and his swift return to ‘two plastic carrier bags filled with cans of lager’ is inescapable.

The narrator of ‘Fucked by the Big Fear’ is equally unlikeable. Misogyny and alcohol go hand-in-hand, it seems, as he judges a one-night stand: ‘She’s not bad looking, a little large maybe but that’s no problem, and I haven’t had a shag in weeks’, and a stranger: ‘a fat woman unselfconsciously adjusts her clothing…She does a couple more small turns, following the flab like a dog chases its tail.’

The speaker has a strange encounter with a girl called Ruth; she angrily states that she is ‘not a fucking whore’ and storms away from him. The narrator notes that he ‘couldn’t want her less’, emphasising his belief that a woman’s worth is based on her attractiveness. Women are disgusting and insane in this story; the coffee shop owner laughs at Ruth’s reaction and states ‘She does that to everyone,’ trivialising her emotions.

Vicki Jarrett’s story, ‘Schrodinger’s Hangover’, initially seems to turn the tables by dishing out some misandry. Jarrett’s narrator seems to be stuck with an insensitive boyfriend:

He was trying to force his hand between their bodies to get at her tits. If he’d just bloody get off it would be much easier but no, of course any difficulty would be her fault, she didn’t even need to think about it.

However, after a while, it becomes clear that we shouldn’t trust the narrator’s judgement. Her boyfriend implores her to be honest and tell him how she’s feeling; she has tendency to pretend that nothing is wrong, it transpires.

This story offers one of the most dichotomous moments in the zine: farcical and poignant. Throughout, the narrator is concerned that she will break wind in front of her partner. When she finally does, she pulls the duvet over his head and traps him under it:

Until she let him out, he could be either laughing protesting or absolutely fucking furious…Together they could be having a muck about and a laugh, close as childhood besties, or they could be heading for a break up.

The story concludes with the narrator considering which ‘reality she actually wanted to be real.’ Rather than focusing on the ins and outs of drinking and its pitfalls, Jarrett uses the hangover as a backdrop against which to explore the importance of communication in a relationship.

Some of the pieces in the zine do not simply depict a hangover: u.v.ray’s practically punctuation-less ‘Paradise Place’ deals with events before the hangover takes hold. The narrator is, again, without hope:

I want to kiss her and I want to fall in love with her and she doesn’t know she doesn’t know that she makes me wish I was capable of falling in love the way other people fall in love and feel things the way other people feel things

Dean Lilleyman’s ‘You Are Six’, written in second person, takes a completely different tack, dealing with a young boy’s birthday. This is perhaps one of the strongest pieces in the zine. Six-year-old Joe is consistently naïve and charming:

You like Charizard because he’s a bit naughty and doesn’t always do what his trainer Ash tells him to do. When your dad is happy and having fun with you he says that Pokémon is a form of slavery…You tell him it’s not slavery because the Pokémon want to do it and anyway the trainers are kind to their Pokémon. Dad says Pants when you tell him this. It makes you laugh when Dad says Pants.

The hangover theme is addressed subtly in this excerpt; Joe recalls that his father ‘trumped really loud and squeezed his beer-can flat’ and that he smells of ‘pears or old apples’. This piece is perhaps one of the most upsetting due to the way Joe regards his father: he is his hero, but the reader begins to realise that all is not well.

Most of the poems included in this issue take on a similar tone: a fragmented attempt to recall the night before, or cope with the hangover. John Grochalski’s ‘Hangover Sunrise’ describes waking up:

you lay there in bed

you’re killing some of Sundayit’s your only day off this week

but you can’t help it

Dave Matthes’s ‘Strange Rainfall on the Rooftops of People Watchers’ begins:

I’ve been drinking since yesterday,

the nails on the tips of my fingers

have begun to peel back toward the skin

and the breaths I take have started scratching

against my teeth

Emily Harrison’s ‘The Other Side To Get To’ takes a different approach to the theme by considering the term ‘hangover’ as a synonym for ‘leftover’ – in this case, memories. The speaker recalls how she and another person would ask: ‘“What do you think was the first thing / Adam and Eve / laughed about?”’

Memories, or lack thereof, are also the focus of Jennifer Chardon’s ‘Unmemorable Memories / Recover / It Doesn’t Matter Anyway Because You Will Forget This’, in which the narrator, having been involved in a car accident, slowly regains memories of her boyfriend, ‘waiting for the day you remember why the one visitor you’re waiting for isn’t coming.’

Paper & Ink is a well-crafted publication, utilising different typographies and illustrations throughout. The zine is most interesting when the ‘hangover’ theme is interpreted loosely, allowing a little respite from binge drinking and liver cirrhosis. In this case, the prose does this more successfully than the poetry; it will be interesting to see what the next issue’s theme, ‘first times’, inspires.