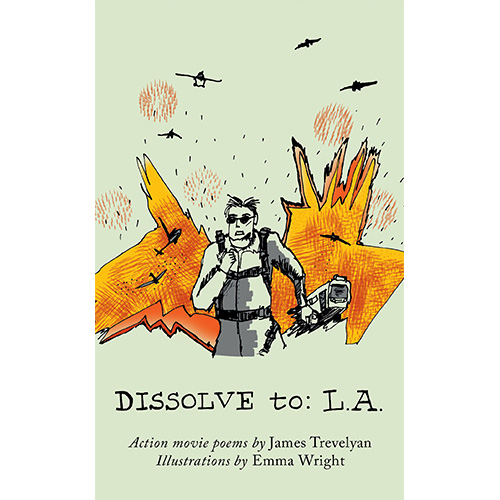

Dissolve to: LA – Action Movie Poems by James Trevelyan

– Reviewed by Jenna Clake –

In James Trevelyan’s DISSOLVE to: L.A., poems are voiced by the minor characters of 1980s and ’90s cult action films. Trevelyan gives space for the unheard to speak their minds, resulting in dynamic, confessional and angry poems. ‘Lloyd’ introduces some of the over-arching themes of the pamphlet:

They gave me a name

and does that not give me life?

More at least than UNIFORMED COP,

NIGHT NURSE or FIRST JOCK,who may have had more to say

but can’t claim to an existence

beyond their scene. I suppose

they forgot me …

Characters are largely concerned with having their final say, being memorable, placing some value in their (usually short-lived) existence – they refuse to be replicable. For Lloyd, his importance stems from his Frankenstein-inspired interaction with the Terminator:

[…] I spoke

to this creature like a brother,its first lesson in humanity: I can’t

let you take the man’s wheels, son.

As most of the poems are voiced by male characters, masculinity is highlighted. In his poem, Hawkins (from Predator) admits:

honestly, I wouldn’t

normally resort to smut,

but I was trying to fit in with guys

who chewed tobacco; menwho ain’t got time to bleed.

I suppose I was freed

as that monster cut through

my chest and strung me up

Hawkins realises that his death was ‘more / than a plot device’: his death (and his poem) highlight ideals of masculinity in action films, the expectation that men will be strong – and perhaps make misogynistic jokes while escaping a dramatic situation. [Ed: so – strong, yet posturing?]

Hollywood tropes are additionally criticised in ‘Girl’ (from Lethal Weapon), in which the speaker repeatedly questions stereotypes:

Why always the potential heroine;

the pretty girl in a silk slip;

breast and nipple carefully displayed[…]

Why a car bonnet that breaks the fall;

the shirt always open, not a hair out of place,

like Ophelia or a centrefold.

The speaker exposes the presentation of women in action films, typically ‘the good girl fallen’: always beautiful, even in their darkest moments. The juxtaposition of Shakespeare’s Ophelia and a centrefold model show that in action films women – regardless of their actions – are reduced to their appearance.

Confessions continue throughout the pamphlet. In ‘Timmy’ (taken from Aliens), the speaker addresses his sister (nicknamed ‘Newt’) by her real name, Rebecca, in a show of sibling rivalry:

how you’d tell dad I hit you when it was just a game rebecca

I’m gonna call you by your name even if you don’t like it

Timmy becomes angrier as the poem progresses, threatening to tear off his sister’s leg to see if it will regrow like an actual newt’s would. At this point, Timmy reveals the source of his anger: his father admitted he loved newt ‘more when he was drunk’ and that ‘even when that monster…planted itself in the dark / … it was your shape that burst from his heart.’

Trevelyan’s pamphlet is convincing due to his ability to create distinct voices for each character. ‘Mikey Tandino’ (from Beverly Hills Cop) has an idiosyncratic voice and an almost aggressive approach: he states that he ‘can talk about himself / in the third person as his god-given Italian-American action movie right’. In this poem, internal rhyme is utilised:

Mikey can brag and incite crime, insist

he’s done his time and gone straight –

unless, that is, fate finds him

in Beverly Hills working security

Consequently, Mikey’s speech sounds full of bravado, almost rehearsed: this is a character that likes to talk. His repetition of Hollywood clichés (‘down there the streets are…paved with money and – / you have to believe me – it’s sunny / all year round’) indicate that he is integrated into the Hollywood action movie scene.

Rhyme also features in ‘Helen’ (from Speed), who addresses her bus driver, Sam:

Remember the one scared of the freeway

and being confined; who sits at the front

of your bus, doe-eyed every weekday;who waits in the morning till three have passed by

for your silver carriage; who cradled your chest

when that bullet ripped in

The rhyme scheme creates an almost sing-song voice for the optimistic and infatuated speaker. In this Shakespearian sonnet Helen takes the chance to finally introduce herself to Sam, and provide them with the happy ending they were denied: ‘I hope they’ll write about us, / Sam, and our too-short time on this too-fast bus.’

In order to ensure that the reader is reminded of who each character is, there are notes at the back that gives them a short biography and lists the film in which they appeared. The poems are accompanied by Emma Wright’s illustrations, black-and-white sketches of the characters or objects pertinent to their stories. The visual is obviously important in film, so the inclusion of illustrations is fitting. The illustrations look like they might belong in the comic version of The Walking Dead, as if most of the characters have been caught off-guard, facing their terrifying fates. Trevelyan’s pamphlet is filled with immersive poems and characters who share their stories, their secrets and their hopes. It is a fascinating and well-crafted read.