Aquanauts ed. by Jon Stone & Kirsten Irving

– Reviewed by Sarah Hymas –

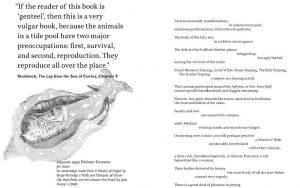

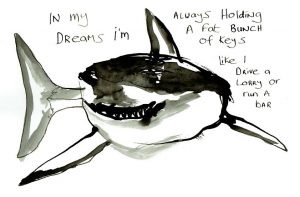

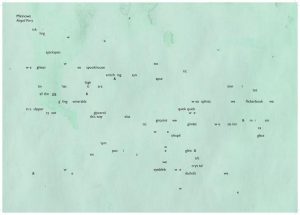

Images: Jon Stone, ‘Delicate Excesses’; Shauna Darling Robertson, ‘In My Dreams’; Abigail Parry, ‘Minnows’; Penny Boxall, ‘Anglerfish’.

Everything about Aquanauts burbles oceanic love and attention to the unseen or overlooked. Sidekick Books have published collaborations ranging from vanishing wildlife, to comics, to experimental poems on gaming, so it is no surprise they should turn their attention to the ocean: that massive ecosystem that keeps our planet in oxygen, absorbs our carbon and regulates climate through the on-going collaboration between microscopic organisms and dinosaur-scale mammals. Aquanauts is small and compact, its size belying what is to be found inside, itself a metaphor for how we mainly engage only with the surface or edges of the sea, missing the complexity of life that inhabits it. The arresting cover image depicts goggles and bubbles, as if a diver stares out at the reader through a submersible portal: but who is underwater here? I had the sense I was already with the diver before I’d even opened the cover, already immersed by the invitation to imaginative play.

Aquanauts seeks to capture the ocean’s vastness, mystery and sheer multitudinous dimension through collage, graphic design, illustration, assemblage, cut-ups, concrete poetry, prose, found text and original writings from twenty eight writers. The voices cohere through their variety and the diverse ways in which the poems and prose are presented. There is no normative vision here, no settling into what will come next. Adding to this medley, the reader is invited to contribute: blank pages or empty lists are presented alongside suggestions for how we might fill them: “flood the page”, “subaquafy the news”, “make a hybrid”, “becreature this page”. I haven’t yet added anything to the book, simply enjoying the space these pages offered, a break in the weather perhaps, before the next event. Each turn of a page offers a new, odd, sometimes factual, sometimes fantastical critter or communication, and I needed respite to avoid getting the bends from taking it all too fast.

We begin in the shallows. In Holly Corfield Carr‘s four-page sequence, ‘Ponds’, each page is dotted with glass ring-marks in which words are glimpsed or obscured depending on the imprint of ‘water’ from the bottom of the glass on the page. In the final imprint, the full text is revealed as a continuous circle of no obvious beginning or end: the hydrological cycle perhaps, evident in the most mundane of places if we remember to look. Deeper in there’s a double page spread of washed turquoise. Abigail Parry’s ‘Minnows’ speaks before a tiny school of these fish: words are broken across the page, as if there is an intuitive communication at play, one we might reach for if we loose the shackles of meaning and allow ourselves to be absorbed in the wonder of these darting movers of the shallows. ‘Delicate Excesses’ is an assemblage from Jon Stone, featuring lines from Burgo Partridge’s History of Origins and John Harper’s Glimpses of Ocean life: RockPools and the Lessons They Teach. As with many of the other assemblage poems, this highlights how the sea is an assemblage of what we’ve poured into it, how creatures are adapting to its temperature rise and acidification. These poets evoke the pleasure and strangeness of ‘prying’ into rockpools, mixing perception and imagination, science and poetry.

Kate Wakeling’s ‘Leafy Seadragon’ (found in depths up to 50m) forms the shape of its title, and blooms in a nonlinear fashion, just as time in the ocean is a field of presence, in which past and future all roll together in the global circulation. What is deep sea was once surface, and will be deep currents again, and the fragmented frills of the poem with their one-worded lines allow the reader to pick and choose how to read it, in what order and rotation. Deeper still, we come to Shauna Robertson’s pen–and-ink shark, in a bold double spread which subverts language and perspective in a simple, very funny way. It provides a punchy interlude from preceding pages which require close reading – literally in terms of ‘Bryozoa’, written in tiny hand writing to emulate the colonies of the bryozoa that share inch-long space amongst millions.

This careful pacing throughout the anthology makes it a delight to read. The shadow photograph of Sean Burn’s ‘the octopus is no hand’, set opposite a blank page for our own play, creates an aesthetically curious, enticing caesura before we dive deeper, to 350m and beyond. Deeper and deeper offshore, the abyssal zone of continual darkness arrives in black pages populated by red, yellow and white text that glows out, still legible but made strange by the surrounding blackness and the concrete poetic forms of spook fish, sea pens, and hagfish. Penny Boxall’s ‘Angler Fish’ is great example of how, throughout the volume, we are asked to turn ourselves (or, perhaps for those more cautious readers, the book) upside down, sideways and horizontal – just as you might in gravity-defying water – in order to see the critters better. Boxall’s angler fish is another excellent example of how language can transverse experience and consciousness to make them blur together, finding those seams where we overlap despite our perhaps too obvious and too distracting differences.

Aquanauts is an oceanic symphony celebrating art and collaboration. I’ve barely traced the surface of what is to be found here, and look forward to spending more time with it. Like the ocean itself, I suspect this anthology will reveal itself and its inhabitants in ever-changing ways with each re-reading. It reminds me that one function of art is to re-inhabit our childhood wonder at the world, and it encourages us not to let that slip through our fingers.