Three Happenstance Pamphlets by Jennifer Copley, Will Harris & Lois Williams

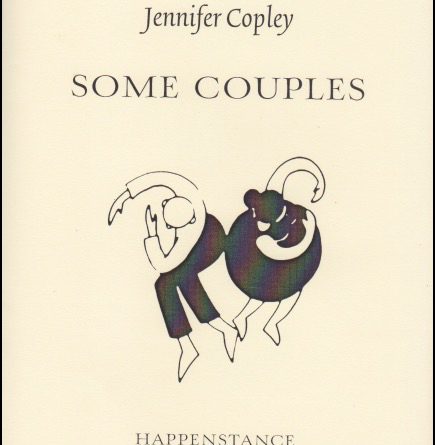

Jennifer Copley, Some Couples

Will Harris, All This Is Implied

Lois Williams, Like Other Animals

– Reviewed by Becky Varley–Winter –

These three pamphlets from Happenstance share a simple-but-satisfying design of cream covers with coloured linings, and a distinct, clean quality in their style, like stones from a riverbed. Other than this, their subjects are very different: Jennifer Copley’s Some Couples contains a series of poems on relationships, variously and vividly imagined; Will Harris’ All This Is Implied explores a variety of subjects, including his Chinese–Indonesian and English heritage, in poems of quiet complexity; and Lois Williams’ Like Other Animals explores the natural world, the body, and place.

The cover of Some Couples features a man and a woman twirling with their backs to each other, looking outwards. The opening poems are attuned to the dysfunctional edges of close relationships, beginning with a self-destructive couple, ‘The Drowners’, who are swept away by love: “Where did you go, you drowners, / unwilling to catch hold of anything that could save you?”

The sequence that gives its name to the pamphlet, ‘Some Couples’, evokes relationships as an environment of their own, whether they’re a garden or a wilderness:

He loved the smell of pears.

When they began to fall

he made her lie with him all night

under the tree.

The four couples here each negotiate power dynamics through compromise and conflict, often using surreal fairytale imagery. ‘Emma and Albert’ remind me of Leonora Carrington’s short stories:

To keep her tall

he hung her on the washing line

when she came home wet with rain.

Under her dripping feet, he said,

the marigolds grew extra lush.

Many of the poems in this pamphlet feel like short stories re-imagined through dreams, evoking whole narratives through scenes and glimpses. In ‘Night Worker’, I wondered whether the protagonist was too stereotyped as a ‘down-to-earth’ working class character, but most of Copley’s couples felt completely realised, expertly conjured up.

‘Fleswick Bay’ contrasts with this more detached narrative approach, adopting the lyric ‘I’ in a way that is (use of the name ‘Jennifer’ suggests) identified with the poet themselves, as if the tide suddenly comes in. Walking on the beach, she watches her partner:

Now you’re heaping up pebbles

shining wet from the tide,

inky-blue, freezing cold.

I watch your searching fingers

with no idea what you’re looking for.

Whether they’re being surreal, playful, or direct, Copley’s poems have a kernel of dramatic power inside them that is difficult to convey without quoting them in full. The ending of ‘Long Distance’ swoops adventurously, in part a love letter to privacy in the internet age (“I want to talk to you in invisible words / that no one can see but you”):

[…] I will weave my words

into the carved curls of a figurehead

on the prow of some great sailing ship

bound for wherever you areand one morning in the future

when you wake in your loft apartment

they will sweep through your open window like rain..

Copley captures the tenderness of frailty and imperfection, messages vulnerable to time. The final poem imagines heaven as a place in which the habits of love become unsatisfying: without small problems to fix, what is there to do?

My mother still irons my father’s shirts

though they never need washing

and my father fiddles with things that aren’t broken.

How he wishes they were!

Some Couples is deeply curious about and in love with love, in all its forms: subtle, sexy, damaging, sustaining, mysterious, compromising, romantic, nostalgic, abandoned and heady. She even finds space for a small sweet poem about friendship. This pamphlet is impressively various, bedding a great deal of feeling into its pages. It’s a whirlwind tour of the heart.

Will Harris’ All This Is Implied impresses me with its reticent intensity. It reckons with selfhood and identity, with an edge of alienation. ‘Halo 2’ concludes:

playing Halo 2, I saw myself in what

I saw on screen and, from Beaver Creek

to Uplift, shot everything that moved:

the birds singing in the artificial trees;

the true self nothing more than the self as seen.

This description of playing Halo 2 is preceded by “paintings of a young Christ […] / his hairless body pricked with blood, aglow” in the first stanza of the poem. Aside from the fact that Christ has a different kind of ‘halo’, I’m not immediately sure why Harris is drawing these two things together. One link may be to do with colonialism: in Halo 2, the aim of the game is to colonise space, alien life-forms being the enemy to the colonising humans, so the poem comments on the shifting perspectives of colonising and colonised. It also comments on the feeling of being identified only through visible signs, such as race. The paintings of Christ show wounds on the skin in order to “advertise his suffering”, as if suffering is only recognised when it is marked outwardly. The speaker of the poem then attacks the alien life that they identify with, as if to expel what they see of themselves, and become invisible. This is, at least, what I think the poem is doing: as the title of the pamphlet states, All This Is Implied, and the opening poems feel like complex puzzles of shy, half-seen shapes.

One of the most powerful poems is ‘Justine’, about a young trans girl:

not knowing who to trust, our eyes

barely meet in the playground. Justine

won’t talk or eat. Her dad has gone

abroad. At lunch I see her poura full salt-shaker in her water, drink

and retch, cry heavy adult tears.

I try to hold her but she weighs

too much. I’m so angry at Justine.

The anger at the end of the poem is completely startling and vulnerable: All This Is Implied expresses emotions more powerfully by being softly-spoken. Harris refers to Wordsworth in ‘Naming’, and seems to follow his dictum that poetry is “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity.” In ‘From The Other Side of Shooter’s Hill’, he writes “though / I could see you were in distress it was like the ambulance you saw / moving slowly, silently across the other side of Shooter’s Hill”, and, in ‘Something’:

Please, let the something

unsaid between us be as pure and

forgiving as the flow of water

from a bathroom tap.

At first glance, the poems in this pamphlet seem as serene as this cool water, then you see that they are not serene at all. At times their restraint risks sealing itself up, but in ‘Allegory’, the poet’s voice seems to fan out, flexing like swan wings. It’s a dream poem in which the speaker dives into water, and emerges changed on waking: “They’re calling me to eat.”

Finally, Lois Williams’ Like Other Animals meditates movingly on place, crossing between England and the United States. ‘In England After Years Away’ describes craneflies that fly through opened doors in the evening, their legs unfolding “like the legs of old porch furniture”:

and because I am the sort of person

who ascribes motive

easily to thingsI think they are persistent

although it is instinctfluttering back into the house,

my luminous house

where I flick off lightsand smooch the cool

cheek of the wallback to my desk in the now-dark

This poem is truly luminous in its details. ‘Noticeboard in Johnson, Vermont’ is also moving, drawing on the experience of war at a distance:

The pronoun makes me stop:

Hang a yellow ribbon for your soldieras if I have one too, an empty seat

laid up with knife & fork at dinner,

The speaker is in a grocery store, and, paying the checkout girl, sees “the your in her eyes”, somehow intuiting anxiety or loss from her expression, the effects of the war spreading outwards, across continents.

As well as this global landscape, Williams draws in to the body’s intimate territory, and several poems explore infertility and illness. ‘On The Occasion Of Not Having Gone To The Same Physician As Angelina Jolie’ is acidic and funny, responding to an insensitive doctor who refers to ovaries as ‘gonads’ and seems to like the word ‘castrated’:

I look at him: goatee like a tiny pubis,

gym rat’s pecs under his white coat, a medical hipster

with the bedside manner of a parking meter.It’s not what you’d say, surely, in introducing your sister

or aunt or mother: Meet N, she’s castrated.

While several poems on this subject are wistful, Williams doesn’t romanticise birth, motherhood, or youth. In ‘At Dodd’s Hill’, the speaker finds a lamb’s docked tail in the grass:

For a moment I’m one with the lamb,

then the farm lad whose chore it was

to dock the tail. I feel the wince

of his innocence leave my body.

Nature poetry is often assumed to be automatically consoling, or somehow painless. As this poem shows, that is not necessarily the case. Like Other Animals takes its place among other living beings with versatility, resilience, and empathy.