Sphere (Are We Where We Are?, Shop Front Theatre, Coventry, 8 Nov 2018)

reviewed by Stella Backhouse

According to Roland Barthes (in a quote I can’t seem to locate, but it sounds like one of his so let’s roll with it), a myth is a value presented as fact. A modern myth is a bourgeois value presented as fact. The disorientation experienced by individuals and societies when myth clashes with lived reality produces unease. It is this unease, perhaps, that lies at the heart of the questions ‘Are we where we are? Or are we in a false position?’.

In Sphere, the ninth and last of Shop Front Theatre’s Are We Where We Are series, seven different writers gave us seven different testimonies, all responding to this central provocation. Binding it all together were Amy Kakoura’s beautiful songs about mythologies surrounding Anansi the Spider, Ares God of War and the destruction of the Tower of Babel.

The result was an intriguing and rewarding glimpse into the writers’ lives and preoccupations. Inevitably, there were some contradictions – most notably between the urge to bring about resolution through action, and the sense of paralysis in the face of a situation that seems immune to resolution. So while Laura Nyahuye proudly quotes her father:

Society cannot define you; all you need is inside you.

Kimisha Lewis’s fictional boyfriend feels powerless to escape the cycle of gang violence and murderous reprisal:

I’ve tried to get out of this life”, he tells her, “and I can’t. I’m past help. I can’t do anything.

This tension between action and paralysis was also evident in Raef Boylan’s poem-story of Liam, a man caught between carving out a middle-class career as an academic, and giving in to the siren calls of the working class culture of his youth. At work, he feels like an imposter, “a hardcore drinker posing as an educator and thinker”. Out on the lash meanwhile, his mates taunt him that “people like you fuck off to London”. When one of them calls him later, his hand hovers over the phone: “Take call? Or delete contact?”.

For most of the performers, the key to resolving their unease lay in the quest for authenticity, that longed-for nirvana of perfect congruence between inner and outer worlds, with no friction between them. Demi Oyediran gave us what was essentially a retelling of Alice in Wonderland, with the White Rabbit replaced by a friendly frog, and the rabbit hole substituted by a pond. Submerged under water, the previously phone-obsessed Oyediran learns to appreciate the simple beauty of nature and “claim her peace”. “You don’t,” her frog guide tells her, “have to be a slave to the status quo”. The evening’s closing words (from Amy Kakoura) were:

tell me who I am, what I’m supposed to do. Tell me something true.

The difficulty is that the concept of ‘authenticity’ raises as many questions as it answers. Refusing to conform to society’s definitions does not guarantee freedom from conflict, as evidenced, for example, by ongoing turf wars over who does and who does not have the right to access women-only spaces; not being ‘a slave to the status quo’ has meaning only if a more comfortable space is available to inhabit instead. On top of all that, the advent of social media makes it easier for individuals to possess multipe personas; and fake news is on the rise.

It was left to Ola Animashawun to explore the alternative: escape from the bewildering complexities of modern life into an idealised – because misremembered – past. “We are all trying to get back to somewhere happier and more secure” he said. And indeed, for many 1950s-worshipping, pro-Leave campaigners in the EU referendum, rather than ‘Are we where we are?’, a more urgent question seemed to be ‘Are we where we were?’.

Assessing the various contributions to Sphere, I began to wonder if our modern interest in identity politics – being the authentic self – and the seemingly supra-national longing for retreat to the past, often presented as opposite ends of the liberal/libertarian continuum, are really answers to the same question. Could both be responses to bewildering complexity – and unease – of modern life? Debating whether this unease is a passing symptom of the times we live in, or an enduring condition of humanity is something that perhaps lies beyond the remit of this series of performances.

But if it’s the latter, then Ashley James Brown’s suggestion that increased use of technology will “leave you more time to be human” is either either a reason to fear the future even more than we do already, or an unmissable opportunity. Our attitude to the future is maybe not so different from Ola Animashawun’s summary of our attitude to the past: “you see what you want to see”.

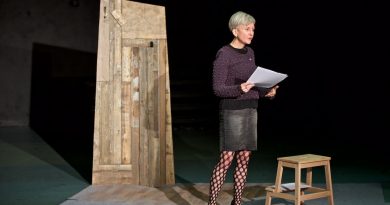

Image of Ola Animashawun by Andrew Moore